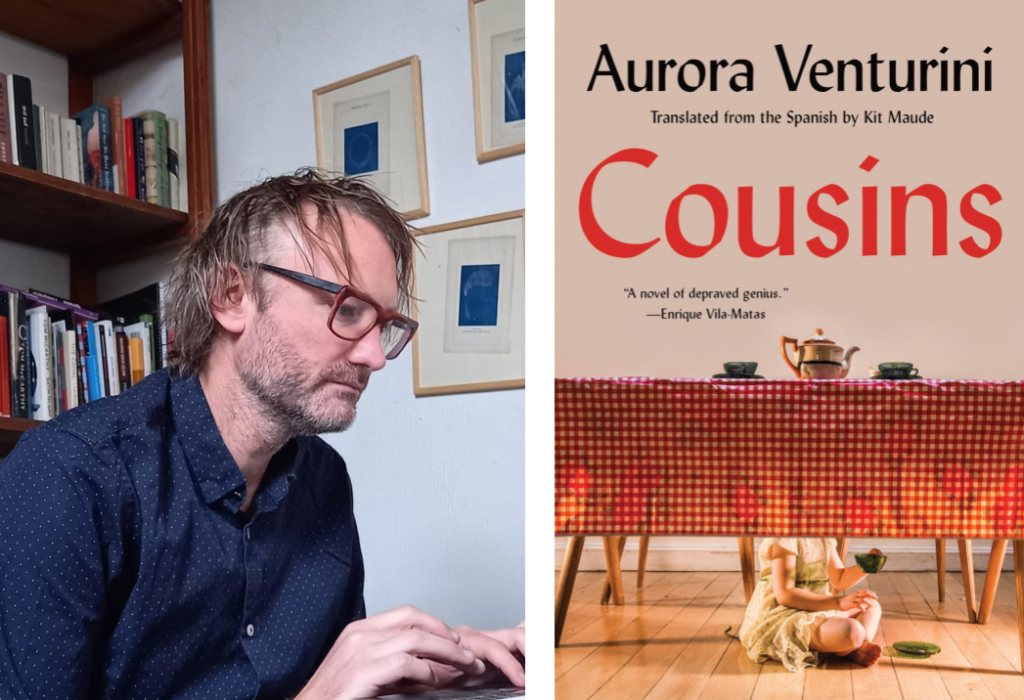

Cousins is a startling document: a beautifully depraved kunstlerroman about an impoverished young girl boosted suddenly and unexpectedly into artistic fame. In turns cruel, crazed, and astoundingly lyrical, it’s a book readers of Fleur Jaeggy or Violette Leduc will love and be horrified by in equal measure.

This is the late Aurora Venturini’s first time being translated into English, by the estimable Kit Maude, translator of such authors as Armonía Somers and Ariel Magnus. Maude and I emailed about Venturini’s mysteriously under-written life and the work of translation.

Kyle Francis Williams: Let’s start by talking about Aurora Venturini. There’s really not much written about her life in English, and I’m hoping you could help fill in some of the blanks. In her earlier life in Argentina, she was a friend of Eva Perón’s; she exiled herself to France for a while and hung out with the existentialists; later, Borges handed her a prize for an early book of her poetry. That’s about all I could find—broad strokes. Could you talk about her life pre-exile? Do you know what her earlier writing was like, or what her and Eva Perón talked about?

Kit Maude: There’s not much written about her life in Spanish either! And she wasn’t especially forthcoming in interviews—I think she preferred to feed the aura of mystery in which she was shrouded to clearing it up. There’s even some confusion about the year of her birth. Fortunately, a biography written by her executor, the writer Liliana Viola, is due to come out this year which ought to provide a lot more information! The basic facts as far as I can tell are more or less that she was born in La Plata, a town about an hour outside of the City of Buenos Aires (home to the provincial government as opposed to the city government, kind of like what Albany is to New York), and studied there, like many of her characters. During that time, she became a committed Perónist, a conviction she stayed faithful to for the rest of her life, and worked advising the provincial “Institute of Psychology and Re-education of Children”—which I think was a lot less scary than it sounds, essentially a branch of social services, from which she gleaned a lot of the material for her work and was also famously where she met and became friends with Eva Perón. She actually wrote a book about that friendship. I think it was her last text, entitled Eva, Alfa y Omega, a kind of experimental hagiography in which she mixes her memories of Evita with imagined scenes from her subject’s life, poems, record-correcting and score-settling (Venturini, like many of her characters, was always one for score-settling). I’m not sure how reliable a document it is, but it does reaffirm Venturini’s keen social conscience, something that comes out in a lot of her fiction. Then, following the coup of 1955 she went into exile in France. But she would say (did say in fact), that you can find plenty of biographical detail in her work; there are certain recurring themes regarding family strife, poverty, the rise into middle class, relative artistic prominence. . . . Hopefully with the biography and further research smarter people than I will be able to construct a more coherent account!

I can speak a little more authoritatively about the actual work, which I’ve read a lot of, and I think throughout this time she was searching for a voice; the register of much of her early writing, poetry and prose, varies from classical to more experimental, there’s plenty of realism but also forays into fantasy and more hybrid forms.

In France, she spent considerable time with Violette Leduc—an author with whom I am unabashedly obsessed. Probably, only because I knew of the connection going in, I even thought Venturini’s writing shared a certain kinship with Leduc’s in having a simultaneously lyrical and spare quality. Could you tell me a little more about their relationship? And about Venturini’s Parisian life among the existentialists, Camus, Sartre, de Beauvoir, Ionesco, et al?

I really like the connection with Leduc (I’m a big fan too)! I think there’s a lot of scope for a critical comparison, if you’re ever of a mind to write one. But I’m afraid I’ve drawn a blank with anything at all concrete about her time in France—what does “socialize” mean? That she was friends with these famous figures? Acquaintances? Just frequented the same cafés? There’s a documentary (with which she stopped cooperating halfway through) in which she describes going to the movies with Sartre and saw him moved to tears. Apparently, she was one of his philosophy students but the extent of their relationship isn’t clear. Again, I’m hoping the biography will help—if there are letters, that would really be something. Having said that, again, there are plenty of hints in her writing—and there’s also the fact that she translated a lot of important French writers; we translators do tend to lurk around the margins of these august circles, part fan, part peer. I think in terms of her writing there’s no doubt that the translation work inspired her own stuff and that voice kept on developing—the 60s saw what I think will be regarded when the studies finally get written as the onset of her artistic maturity.

At some point Venturini returns to Argentina, where she passes away in 2015. Cousins was her last(?) book, published in 2007. It won the New Novel award, and is considered her masterpiece. What do you think it is about Cousins that brought her into the spotlight in her 80s?

I think she returned in the 80s with the return of democracy, but I could be wrong (sorry to be so vague!), feeling thoroughly overlooked and undervalued. At some point during this time, she developed a perhaps unhealthy interest in the occult, which also comes out in some of her work. She self-published a bunch of texts and others with small presses but to little fanfare—I’m not sure she would have made much of an effort to ingratiate herself to the literary establishment. Then in her late 70s she writes Cousins, supposedly all in one go, definitely on a typewriter. The romantic in me imagines it as a kind of “fuck it” moment in which, as often happens when you have nothing left to lose, everything just clicked, the voice she had been honing throughout her artistic career was now razor-sharp, as was her sense of humor, righteous indignation, and impatience with classical, “proper” style, all those periods and commas. She won the Página 12 award in 2007 (she responded to news of it with the rather characteristic, “Finally, an honest jury.”) and got some overdue recognition; but it wasn’t her last book. She wrote a sequel to Cousins, Las amigas in which we meet Yuna again as an old lady, and it seems to include plenty of autobiographical nods as well. I think Cousins struck a chord with its originality and authenticity—I know I keep repeating the word, but the voice is so key to its brilliance; you really couldn’t mistake Yuna for anyone else. Then there’s the timing, sometimes comic, sometimes dramatic, and that sly, Nabokovian wit. There are so many ways in which literature can be great but I always think a good test is whether you’ll be thinking about a book in a month or a year’s time, and Cousins passes that with flying colors.

I think you’re right that Venturini’s voice in Cousins is such a huge part of its appeal. Yuna really is like no one else, so idiolectic, like Nabokov’s characters, or Faulkner’s, with a rhythm entirely her own. Were there particular challenges and/or pleasures translating that voice? I have to imagine some of these longer run-ons were, without any of their periods or commas, were, let’s say, Fun.

So much fun! I’m sure people will feel we’re exaggerating when we invoke names like Nabokov and Faulkner, but honestly, I can count on one hand the number of times I’ve felt the electricity that came with reading Las primas (Cousins) for the first time. I’d also mention perhaps an even more canonical text; Yuna’s got a lot of Holden Caulfield about her. That crisp, bewildered, angry gaze . . . and then when, at moments of high emotion, her sentences break down entirely into the stream of images—it was very important to me to preserve them as they are in the original, nonsensical but also utterly empathetic, when Yuna’s at her most endearing. They also tend to be celebratory, which is interesting.

Is it that voice that attracted you to translating Cousins? How did this book find you? And, once it had you in its clutches, what did your translation process look like?

I came across Las primas with its latest reprint in an excellent set of editions by Tusquets Argentina—the first time I think that Venturini’s work has ever been properly brought together and organized. The great thing was that after I fell in love with Las primas, the other volumes came in quick succession, so I was able to read much of her oeuvre fairly rapidly instead of scouring second-hand bookshops for what would have been years, most likely. That was, I think, crucial for getting an idea of where Las primas came from, the themes that had always been significant to Venturini, how she developed, and what was absolutely new (in her seventies!). Then it was just a case of finding the right voice in English—and that actually came fairly easily. To get the translation commission I had to do a sample and I remember almost from the first line something seemed to have clicked, it sounded right (although of course it still went through hundreds of versions, and once I’d got it, it went through a bunch more). Then it went to the US and UK editors, Kendall and Emmie, who took the text to another level; it was a privilege to work with them. After that it was a question of defending the lack of punctuation and grammatical eccentricities from the copy editors and proofreaders.

As well as Cousins, you translated a book a few years ago of which I am a huge fan, The Naked Woman by Armonía Somers, for The Feminist Press. It is a similarly strange and wonderful book, about a headless woman who terrorizes the local village, written by a writer who may be just as enigmatic as Venturini. How do you go about choosing your translation projects? From my perspective, it looks like you seek out works that are purposefully difficult to translate or classify.

Oh! Hooray! I loved that book, and the other texts I’ve been lucky enough to work on by Somers, she’s another extraordinary writer with a unique voice who ought to be much, much more widely known. I’d love to be able to tell you that I’m in a professional and financial position where I can pick and choose my projects but the truth is that I usually have to take anything going. Having said that, when there’s a book I really like, I’ll put more effort into the hustle. For Cousins I used up my only high-end publishing contact to get into the reckoning for the translation. I don’t set out to make my life difficult but the books I pitch tend to reflect my personal tastes, which I suppose often veer into the weird and wonderful. That’s where the best stuff is!

I’d like to hear more about that first line. My first introduction to being obsessed with how translation works is probably the opening line of Camus’s L’Etranger. Cliche, I know, but I find the opening sentence of anything now to be so incredibly important. Could you walk me through where you might have started to where you ended up?

Oh, fun! First lines are important! Here, the great thing is that Venturini plunges you right in—Yuna’s off from the start, almost as though we’ve stumbled into the middle of a conversation. The original reads like this:

Mi mamá era maestra de puntero, de guardapolvo blanco y muy severa pero enseñaba bien en una escuela suburbana donde concurrían chicos de clase media para abajo y no muy dotados.

The “maestra de puntero” is potentially ambiguous because “puntero” means pointer, but puntero is also used sometimes to describe someone who heads up a team, or is just very good at something, so Yuna may have misheard praise for her mother and channeled it into her hatred for the damned pointer. So, we’ve started with a joke! Then the “guardapolvo blanco” is interesting because it’s literally just “white coat”—both teachers and students in primary school in Argentina wear a white coat over their clothes as an affordable, egalitarian uniform—and that’s what I had but the editors rightly thought that might cause confusion for readers in English, hence “uniform.” In the second half we come to two delicious phrases, “enseñaba bien” and “no muy dotados”; “taught well” and “not very bright.” Yuna must be quoting someone, most likely her mother herself but in relaying the information to us like that she’s made it her own, with the addition of “muy severa” (very strict) which we can assume came from her. So immediately we’re into Yuna’s world of pure visual observation, the pointer and the uniform, and second-hand descriptions that she repeats with no sense for the social niceties:

My mother was a teacher with a white uniform and pointer, she was very strict but taught well at a school in the suburbs for not very bright children from the middle classes and below.

To finish up, I want to ask how you got into this line of work. What brought you to Spanish-language literature, and what do you think has kept you there to fight for these books to be read by English-speaking readers?

Well, I studied North and South American literature and history at university, which involved spending a year in Argentina, where I was lucky enough to have a personal tutor who was one of the world’s experts on Silvina Ocampo—an extraordinary writer if you’ve not come across her before. So, when I got back to the UK, I was buzzing about all things Argentina. Then, once I’d graduated, I lucked into a job at an independent publisher in London, Peter Owen, who happened to specialize in translations. So, to an extent, I learned the trade there, especially the business realities, which I think pass a lot of people who’ve led a more sheltered academic existence by. It’s a small but amazingly vibrant world, the world of independent publishing and translated fiction; I truly enjoyed being in the thick of it. Then at some point it occurred to me that the deepest immersion I could get into this literature that I love was to become a translator myself, and to do it well I’d need to spend a lot more time in Argentina. So, I moved out here over a decade ago, and it’s gone OK!

And, lastly, are there any authors you have your sights set on as ones you desperately want to translate?

So many! Skipping over the texts I’d love to retranslate, for fear of causing offense, although I don’t think I’d bother anyone by saying I’d love to have a shot at the Quixote one day, there are some extraordinary authors out there: I’m currently pitching the not-at-all-untranslatable Ana Ojeda, who writes in gender neutral Spanish as part of a wild, popular culture inflected stream of consciousness style. Marcelo Cohen, one of the greatest contemporary writers in Spanish, is barely represented in English. There’s a brilliant book by the Argentine writer Luciana De Luca I’d love to do, another by the Spanish writer Natalia Carrero that would come with extraordinary line drawings . . . quite a few more. And I also have a finished translation of Armonía Somers’s masterpiece, Only Elephants Find Mandrake, if you know any editors not easily spooked by “difficult” writing.

Kyle Francis Williams is a writer living in Brooklyn. He is an Interviews Editor for Full Stop and a recent MFA graduate of the Michener Center. His fiction has appeared in A Public Space, Southern Humanities Review, Epiphany, and Southampton Review and Joyland. He is on Twitter @kylefwill.

This post may contain affiliate links.