When I first encountered Caelan Ernest’s poetry at a Club Wonder reading in Bushwick, I was mesmerized by their expertly articulated performance, their immaculate vibe, and their hypnotic poetry. Their debut collection night mode (out now from Everybody Press) is a serial poem dripping with sex, sci-fi, theory, and the experience of becoming a self—and becoming, and becoming, and becoming.

This year we’ve chatted frequently on different platforms, culminating in a zoom call last month. Robots transcribed our conversation about the internet, Caelan’s inspirations, self-censorship, poems as portals, and play vs. performance. The following is an edited version of those robot’s transcriptions.

Hannah Lamb-Vines: One of the things that strikes me about night mode is the particular vernacular you use, a grammar it seems like you’ve created. Can you tell me about where that came from?

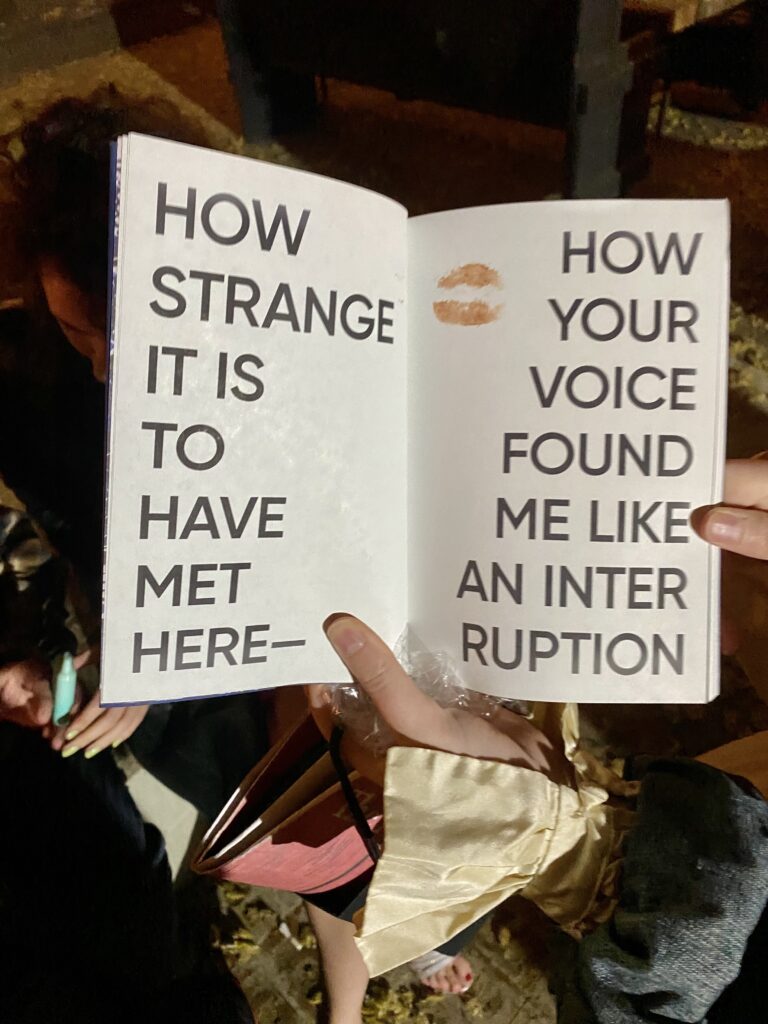

Caelan Ernest: The language play in night mode stems from thinking about text messages–coded language you might use when texting your friends, or while messaging on hook-up apps. I’m thinking of emojis – even though there’s no actual emojis used in the book – and playing with punctuation and enjambment. I was heavily inspired by r. erica doyle’s work. Although our approaches to poetic language have their differences, her usage of form in her collection proxy heavily inspired this book. Encountering her work for the first time felt like an invitation to experiment with language, with a digital artifice. So, the language is coded. Coded and also coated.

We’ve spoken before about night mode having a sci-fi lineage, and the world building process you took on to write it. I’m thinking about how visual the book is, and wondering where the visual form of the poems – the way they take up space on the page – intersects with the world building.

A few years ago I heard a writer speak about using blank space, primarily with poetry but also with prose, utilizing blank space to blur the horizon of the page at its edges. That became something very literal that I appropriated in the book. It’s in “pink(ing)” in thinking about the beach, but it also was a helpful frame for the book. It shattered my understanding of poetics, allowing a rupture to happen.

I didn’t come to poetry through craft. I came to poetry through music and play. Allowing myself to do this book-length, weird, surreal, glitchy poem opened a whole new world in my poetic practice and praxis. It felt like a carnival.

It’s so glitchy! In “pink(ing)” there’s not only blank space that erodes the poem, but the sentences and statements themselves are eroding. A period replaces the object at the end of a sentence. It’s kind of a headfuck, because a period connotes an ending, yet these statements are clearly unfinished.

“pink(ing)” was the hardest poem to write in the manuscript. When I started to get at the gut of what I was trying to say, and what was perhaps missing from the rest of the book, I started to realize that I kept censoring myself. I incorporated those self censors into the language and the punctuation.

The performance of censorship – you get to say the things, get them out, but you do it for yourself. That doesn’t mean everyone else needs or gets to hear it.

Exactly. It’s a weird, delicate balancing of play, and also vulnerability. It’s like, how much am I revealing? How much will the censor reveal? In what ways is the censor violent? And does that censoring create a different relationship between the reader and the narrator – or, rather, the voice(s) throughout the book?

And there are so many voices in night mode. I’m wondering if these are performances of the self, the various selves – because the speaker does refer to multiple versions of themselves. But there also seem to be conversations happening, voices from outside. How did you approach the voices?

How I approach the multiple voices throughout the book varies depending on the space that the speaker is occupying in each poem, which affects how they’re choosing to speak. As an example: in the conversational poem “put your phone down for a sec”, the conversation/monologue occurs right before a party or a night at the club. The “you” in the poem is someone that’s like a confidant to the speaker, a “sis”, and because of this interpersonal relationship, the language is coded more intimately than in some of the other poems. The language in “pink(ing)” is censored; the language in “night mode” feels like a text thread or an exchange on a hook-up app; the language in “THIS TOPIA” is glitchy.

In thinking about the external voices and the “you” and the “I” throughout the book, I had to position the spaces within the poems, whether digital or organic, as their own worlds, or “topias”. This is perhaps most apparent in “THIS TOPIA” where the landscape of this poem features headless torsos of men scattered like trees blooming in the horizon.

There’s another voice that ruptures through the speaker’s in “THIS TOPIA” which seems to come from elsewhere, another time, another poem. And the system has its own voice, too, and it enacts a violent censoring that can “gloss” you, with the implication that you will be killed, rebooted.

Although, I suppose my approach to the “voices” in night mode was never exclusively about literal “space”, but about the exchanges and relationships the speaker develops with them, alongside the bodies, the desire, and the feelings of abjection. How encounters change you.

When we were scheduling this interview we joked about email being an uncomfortable space, where the expectations are that you’ll be professional and pack as much information as succinctly as possible into one text box. When you’re in that “space” you do perform a different version of yourself, right, no matter how much you reject or disparage or try to disrespect it. I was wondering, who are the different selves that you occupy on different online platforms?

Oh, I love this question. As I’ve gotten older, I do my best to streamline as much as I can, while leaving room for all the different versions of me that I’ve created. As I write in “put ur phone down for a sec”, “if there’s going to be multiple versions of me / don’t u think i should start referring to myself as plural / (as singular) / like i did on my story / they / they / they”.

A new avatar, a new identity is forged every time you create an account. What do these platforms call for us to do? Instagram is image and video-based, while Twitter is primarily text-based. How do these channels ask us to perform ourselves differently on each, in order to “succeed” on them?

I consider myself a child of the internet, even though I grew up just before it really took off. I made a Myspace account in middle school, then AIM, then Facebook, then Tumblr, and so forth. A few of these platforms really helped me in my coming of age, teaching me new aesthetics to try out in my personal style, as well as learning different styles of communication.

Although I refer to it as “streamlining” my social media presence above, I think what I mean to say is that I no longer care about separating my personas on each platform; I try to resist that convention and blur the lines between my social media channels. For example, I post whatever I want on my Instagram account, from selfies to photos of the ocean to my own poems to pictures of my cat to professional updates to… just about anything else. In that way, I have grown to allow myself to be impulsive by posting what I want in the moment. And not thinking too much about what I’m posting – not worrying how many likes or comments or views I’ll get – makes me realize just how much I’ve grown.

Since night mode plays with the visuals of language and the way the poem looks on the page, I wonder if you were looking at, thinking about, or inspired by any specific visuals while you were working on it.

I wrote night mode during my MFA program, and as part of the process, I tried to engage with a variety of material–a lot of music, movies, books, theory, and short films. I found most of my inspiration in unexpected places. My MFA program didn’t separate my cohort by genre, and I ended up receiving some of the most useful critique and feedback from my peers who weren’t poets.

I remember first watching Fuses by Carolee Schneemann and being mesmerized by the erotic, intimate, neon-glitchiness of the short film. night mode might not always be as vibrant, but at its most vibrant I can credit that film.

As a visual, I kept returning to Hajime Sorayama’s cyborg artworks while working on night mode. While I don’t have one specific way of visualizing the cyborgs and bots in the book, it was helpful to look at Sorayama’s imagery as a reference.

Another image I worked on developing happened during the editing process: the ocean. I’m from Rhode Island originally, and I spent most of my childhood summers by the water. I lived a five minute walk from a pond that connected to a beach. As I edited the manuscript, even just a few months from publication, I worked with my wonderful editor to find more places to connect back to the ocean. Perhaps not a central image, but returning to the ocean as a grounding throughline between shifts in identity.

One of the first things that comes to my mind alongside the term “night mode” is the setting on our phone—the subdued, less vibrant mode. Why did you go night mode instead of day mode? What does that say about the poetics that you’re working with here?

To promote and contextualize night mode, I’ve participated in a couple of other interviews, and one of my favorite points of conversation is around what “night mode” actually is, and all of the different meanings it can take. Hearing other people’s perspectives has actually introduced me to more ways of viewing night mode than I imagined. It could be night vision goggles, allowing one to see in the dark with a thick green overlay. It could also be “dark mode” on the phone, where the phone’s user opts for a darker color palette. Another way of looking at it is when a person heads into the night, out dancing or meeting a date to hook up with.

My intention isn’t for “night mode” to mean anything concretely or definitively. Rather, it’s a frame for the book and the poetics. Whatever it conjures the reader to visualize is part of the experience in being in the world of night mode, or “the topia”.

I think about how so much of our professional life is lived on the screen, so when our phones go into night mode it’s a signal that you get to step away from the rigid, professional, in many ways immaterial performance of the self, into something that’s more tangible and erotic, felt bodily. We’re still on our phones, but they’ve become an avenue for that eroticism as opposed to a stage for the performative professional version of ourselves.

Did you see that tweet early in the pandemic? It was something like, “Signing off work, time to close my bad screen and open my good one!”

[laughs] You so frequently describe your writing as play. Recently I’ve been thinking about the relationship between “play” and “performance” and the different attitudes we take towards each, despite their similarities. How are the two connected for you?

I enjoy writing the most when I allow myself to play, which is certainly how night mode came to be! I allowed myself to explore, experiment, and just have fun with the process, which is, in part, why I think it organically developed into my first collection. This is not to say that the entire experience of writing and editing the book was fun (there were many, many difficult and painful moments), but overall, making night mode was a great ride.

I think one of the reasons we have different attitudes towards “play” and “performance” is that when we play and experiment with our craft, what we create doesn’t always amount to anything publishable or presentable – and that’s okay! Part of the joy of playing is that we learn new things about ourselves and our relationships to craft.

Looking at the poem “put ur phone down for a sec”, it references queer theory, and how gender expression itself is a performance we’re doing constantly, whether or not we’re actively realizing it. In that way, I think of gender expression as a perfect example of where performance and play connect: It’s both fictional and true. It’s real and fantasy.

Ultimately, it’s my opinion that to be a good performer, you have to be down to play.

I love that! Is there anything you’d like people to keep in mind as they approach night mode as a text or a reading experience?

Although I consider night mode a book-length serial poem, my hope is that readers understand that the events happening in the poems aren’t necessarily chronological. It’s not a linear narrative. Each poem takes place at different points in time, from different vantage points. With this said, I would still encourage everyone to read night mode from front to back, beginning to end, on the first read. If a reader returns to the book for a second read, my hope is that they would make discoveries they didn’t have on the first encounter.

It really feels like each poem is a portal into this world that you’ve created. Time and space don’t really matter because you land in a complete creation. But each is dependent on the other creations.

That’s spot on. Definitely.

Is there anything you’re working on right now that you’d like to talk about?

Right now I’m finishing the first draft of my second collection, titled ICONOCLAST, also coming out from Everybody Press. It’s slated for publication in 2024, and although there are overlapping themes with night mode, it’s extremely different formally and in its conceit. Watch out for it!

This post may contain affiliate links.