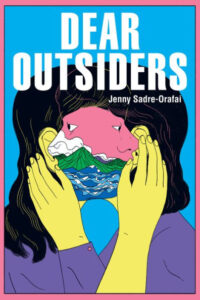

[University of Akron Press; 2023]

Who lives in the beach town we visit every summer? Who works in, walks by, or rages at the souvenir shops? And when was the last time we remembered to consider them?

The core of Jenny Sadre-Orafai’s fourth poetry collection, Dear Outsiders, pinpoints intersections between magic and imagination, landscape, and identity tethered to geography. It documents the strangers (or strangeness) wafting in, out, and through a childhood sanctioned by tourism. Split into two sections, the collection follows siblings who live by the sea, and when displaced by their parents’ death, move into the mountains. Burdened by tourist traps and constant “guests,” the siblings understand their homes by investigating the people, warnings, and patterns around them. Sadre-Orafai hands us a map of prose poems through which we navigate where childhood dies or persists, and where it becomes indistinguishable from the space around it.

A sonic and linguistic mirror to the sounds of land, Sadre-Orafai’s poems are rife with commands, demands, resistance, and futile motion. They yearn for the earth and simultaneously shake it by the shoulders: “The ocean’s an / animal head on a wall, and we can’t see the body.” Bursting with color and texture—“red cellophane fish,” “stars leggings,” “blue on blue”—the vignettes pair vibrant images with desperate speakers longing to make sense of their lives.

Dear Outsiders critiques our capitalist shackles on the environment; it immerses us in birds, bears, botany, and abundant currents, but never allows us close enough to claim ownership. Through its decisive syntax and surreal narrative, the collection asks for revival. Sadre-Orafai considers the indestructible earth and the not-so-indestructible lives within it, as well as the spaces we mold for our entertainment and the spaces we ignore. The collection immediately establishes a theme of ownership and consequence in its opening poem, “Topographies”:

Our mother’s body.

Not our mother’s body.

Our father’s body.

Not our father’s body.

A grief bleating at our shores.

A landscape breaking.

This story is not one with a happy or resolved ending. In Sadre-Orafai’s eco-poetics, even the townies’ bodies are not theirs. Instead, the siblings in the collection are claimed by a land that’s invaded by tourists. They can map “an egret with a fish speared on his beak,” but not “hands twisting out the wet from a shirt.” “Topographies” opens with lines that repel each other, showing what can and cannot be charted by the speakers. The siblings’ mother is theirs and suddenly not. Without a doubt, grief and fracture are at play. The firm couplet structure of “Topographies” bounces between snapshot moments that are abruptly lost, and sets up a narrative with constant grief.

Sadre-Orafai expertly bottles turbulent feelings of childhood. The oceanic poem “Low Recitation” examines how children’s perspectives on birthplace develop. “What is plateau? What is / plain? Basin?” And then, “How / many of you were born right here? What is a current? Crest?” Partaking in a geography lesson with the siblings, this poem quizzes us, challenges us to prove we know the land at stake. The children “try to see different pictures” in the map. They try to hear their parents “with their newspapers in the morning.” I read this poem as the siblings reclaiming some of their home through their imagination. The poem “True/False” carries the same curiosity:

How many tails are in this piece of the gulf? Whose idea was it to

make so much water? What happens when water becomes a gas? How

long can you hold your breath at the state fair? Who is the sun and

who is the moon?

The siblings want to find magic in their home. But they know—“This is the rip that sweeps bodies under and into her chest.” The whimsy of “Low Recitation” ends with death. The harsh ocean holds no compassion for those who play within, just as the tourists hold no compassion for the space they invade. This ending can be read as a literal death; drowning is a consistent motif in Sadre-Orafai’s collection. But the “rip that sweeps” is also the force that devastates the siblings’ imagination.

Directly after “Low Recitation” is “Lost & Found,” a poem that underlines the siblings’ reality: No matter what, they can’t escape the visitors. They can’t ignore the tourist-trap stores “for people who aren’t us / to feel good about buying.” The visitors “kick sand” and trample the townspeople’s belongings. Sadre-Orafai’s imperative, insistent verb use highlights the tension of growing up, especially in a place that disregards you. Unable to avoid the intrusive tourists, the siblings “point out what they should take pictures of even though it’s nothing” (“Locals”). Dear Outsiders’s seaside setting is stripped of playfulness as that too is conquered by the capitalist tide of tourism.

The hometown of Sadre-Orafai’s siblings is overtaken by price tags and the out-of-towners’ need for escapism. In “Affirmations,” the siblings say, “Somebody tell the starfish we’re sorry for / buying their bodies.” They see this damage to the land, a damage they will inevitably suffer as well. Sadre-Orafai’s cry to the landscape slaps us harder than a hurricane. What magic is there in a land we commodify? And, when growing up in this economy-driven, seasonal, almost liminal place, what is a childhood robbed of? What kind of grief is that?

As the collection moves into the mountains, Sadre-Orafai’s questions return, though without any attempts at imagining oneself in the cartography. “At Our Lessons We’re Given a Map” concludes with:

Use your pointer finger to show me land. How many of you were born

right here? Home has been constellated. Flung. Do you know where

you are?

Not only are the siblings geographically displaced, but they become orphaned. While parts of their old lives can be conjured, the act demands incredible effort (“we translate the leaves’ / turns like our father’s face”). Sadre-Orafai introduces a secondary loss. As the children grieve an abandoned landscape, they also grieve their parents, who are so intimately tied to the body of the earth: “Our mother’s body. / Not our mother’s body.” Are the mother and father from “Topographies” people? Or the ground and water around us? Sadre-Orafai fuses the parent with the land. We must figure out which is which, if there’s any difference.

The collection grows into a melting pot of estrangement, ownership, locale, and their crosshairs. Living in the mountains, the children cling to what water they can, but become outsiders themselves, learning a new culture, a new terrain. The poem “There’s a Gap in the Land” highlights this discomfort:

There’s a gap in the land and it’s where we want to hide.

We want to cover this whole town up, with their cow patties and cow

tipping and toilet paper rolling. They leave markers where people die

if it happened on a road. We want our parents to arrive breathing in

their mouths saying we just wanted to know that you would be okay

without us.

The speakers want to reject the livestock and the residents’ traditions—they want to cling to their home. They assert, “This is where we became / orphans, where we stayed on top of the water.” It’s lovely how Sadre-Orafai employs imagery that’s direct and zoomed in, like the roadside grave markers. These moments evoke the siblings’ grief and struggle to acclimate after loss.

Dear Outsiders is the pruning of your hands, the crab that evades your eyes; it is the looming summits, the whistling birdcall that follows you for days and refuses to explain itself. The siblings’ drive to divine childhood from landscape is Dear Outsiders’ persistent pulse. The surreal, poignant nature of Sadre-Orafai’s poems left me standing on the edge of a vast expanse, waiting to be sucked undertow. After reading Dear Outsiders, I peered at the Flatirons outside my apartment and felt something new and urgent. Lyrical and imposing, Sadre-Orafai’s work challenges us to consider what and who we overlook, what the earth is saying, and whether or not we’re really listening. The collection asks, a vacation? and then dismantles the entire notion.

Bri Gonzalez is a queer Chicana/e writer, as well as an MFA candidate and instructor at the University of Colorado Boulder. Their work can be found or forthcoming in Devil’s Party Press’ Solstice: A Winter Anthology, ERGI Press’ Trickster Anthology, Juke Joint, Bear Creek Gazette, Janus Literary, and more. She serves as Poetry Editor for TIMBER and plays an inordinate amount of D&D. Check Bri out at bgwriting.org or @bg_writing on Twitter.

This post may contain affiliate links.