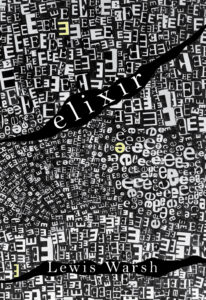

[Ugly Duckling Presse; 2022]

Despite more than fifty active years as a teacher, publisher, novelist, and poet, when Lewis Warsh passed in late 2020 it felt less like the poetic equivalent of a gentle fade-out and more of a skipped record, skidding suddenly, unfairly toward the silent loop of its run-out. How pleased I was then to encounter a new book of his verse last year, Elixir, beautifully presented by Ugly Duckling Presse. Reencountering the generosity of Warsh’s poems in a year full of isolation and discord proved, once again, to be the catalyst I needed to start returning to a space of life after so much death. These posthumously published works renewed me, providing a continued hope through their music, their memories, their moments of sudden, arresting prophecy. “All the ghosts are still alive,” he writes in the poem “Here We Are,” in a voice that interrupts its own passing.

Ever since I first found a well-loved copy of his 1987 collection Information from the Surface of Venus more than a decade ago, Lewis Warsh’s writing has occupied a special place in the heart of my writing life, a north star guiding me out of doldrums and moments of lethargy. His poems have helped reorient me when I’ve lost my way in the weeds of words, helped reconnect me with the power of lyric writing, its ability to draw a reader in through an attentiveness that resolves itself within a musicality of the everyday. In book form, this attentiveness generates a linguistic antidote, an elixir for treating our repeated habit of forgetting; from the forgetting of the seemingly insignificant things that hold together our material selves, to the vast range of vibrations that compose all existence on a cosmic scale. For Warsh, as for many of us, music is a force that perpetually moves us, both emotionally and physically, “consecrating a space for the joy of hearing,” as he writes in the poem “Nine Hymns.”

In this sense, lyric poetry has the capacity to link the vast and intimate spaces of our lives, riding the waveform of existence as it rises, topples, recedes, and repeats itself. Lyrics, both sung and read, are mediated by our senses, our attunement to phenomena and their backdrops, patterns, and novelties. In Warsh’s poetry, the effects of subtle detail, variations to the rhythmic filigree, shift the overarching sonics and imagery, with a modesty that belies his considerable talents. His writing draws the reader in, with an intimacy that encourages listening and looking more closely: “Even the perennials / need to be replenished / in the spring // it takes some time for / the truth to sink in” (Grand Hotel). In Elixir, Warsh continues his lifelong journey as a collector of sound and image, dropping lines that trace a basic connectedness between the speaker and the witness, the singer and the audience: “This is the derivation of cogitare, to collect one’s thoughts” (“Anything You Say”). These poems embody an attention that becomes both universally quotidian and deeply intimate: “It’s possible to look at things through someone else’s / eyes” (“Not Guilty”).

This paratactic, self-as-other attentiveness is also reinforced through another sensory phenomenon, Lewis’s repurposing of song titles scattered throughout the book. These sample the voices of others in a way that mimics both his own poetic line and pop music’s often ambiguous, yet unique emotional impact. Warsh’s beloved songs are mutable bodies, points of reference that can be revisited, reengaged in conversation, but never from the same position and never to the exact same effect: “Time is like a river, no, shit, it’s like / a song” (“On the Western Front”). Popular songs are often a reminder of our non-linear connections; something becomes stuck in our heads, an earworm circling in nested patterns or rhizomatic melodies weaving a tapestry of social experience into the personal: “One time I turned the radio up loud in my head / I changed the station until someone was saying my name” (“The Open Air Theater Moves Indoors”). Warsh employs these moments of encounter as a series of coordinates, guiding poems along their felt, experiential meanderings: “I was singing a song in my head / It was ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ / when a cloud passed in front of the sun” (“The Open Air Theater Moves Indoors”).

Songs of all types score these poems, often emerging like ghost voices from Jean Cocteau’s Orphic radio. The mixtape of Elixir is generous and ranging: populated by scraps of Dizzy Gillespe’s “Salt Peanuts,” “Midnight Train to Georgia” by Gladys Knight & The Pips, The Beatles’ “Strawberry Fields Forever,” “Claire de Lune” by Claude Debussy, and “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” by Glen Campbell. A childhood memory of the haunting “I’m Walking Behind You” by Eddie Fisher sticks out to me in particular, emerging as an eddy, swirling and backchanneling along our drifting stream of consciousness inside the poem “Not Far.” The song functions as a lucid remembrance, an emotional anchor, and observational pause: “There’s / a blimp out the window frozen in the / sky above the Bronx and the radio / is playing . . .” These immediate interventions of music stretch the collection’s seemingly direct observational poetics into a field of surprising circular encounter, as favorite tunes both immediately arrest and link disparate moments in time.

In this way, the music of Elixir makes it a book of absented endings—a travelogue that anticipates a destination that never exactly arrives. Abeyance and restraint mediate the warmth throughout the collection. Prophetic memories of pop culture detritus and social fault lines are gently and generously surveyed: “There’s only the present / like a movie played backwards / with a cast of thousands / hanging on for dear life” (“Old Flame”). Songs emerge as companions, overheard conversations, the link or catalyst between sensory impressions. These songs then form the collective mind of the city, making these poems familiar, comforting, and convivial in the midst of their bricolage construction. Warsh suggests that the presence of music in public city spaces intercedes and blends with our own distracted mind, providing a soundtrack, a derailment to our train of thoughts, or a sonic pillow to rest our heads amid the chaos.

In striking interventions of magic and medicinal song, the poems of Elixir offer balm in the midst of uncertainty and grief. Its strength is its sweetness, which will continue to live within all of us who have experienced its pleasure. But most importantly, Elixir reminds us of the fullness of life, of melody, never a straight line, but rather a round, a chorus joyfully repeated again and again: “It was like yesterday, today and tomorrow rolled into one” (“Single Occupancy”).

Jamie Townsend is a writer and editor living in Oakland. They are the author of several poetry collections, most recently Sex Machines (speCt!). They are also the editor of Beautiful Aliens: A Steve Abbott Reader (Nightboat). Currently, they curate the bicoastal magazine project Elderly with Nick DeBoer and the East Bay salon series Just Like Honey with Ivy Johnson.

This post may contain affiliate links.