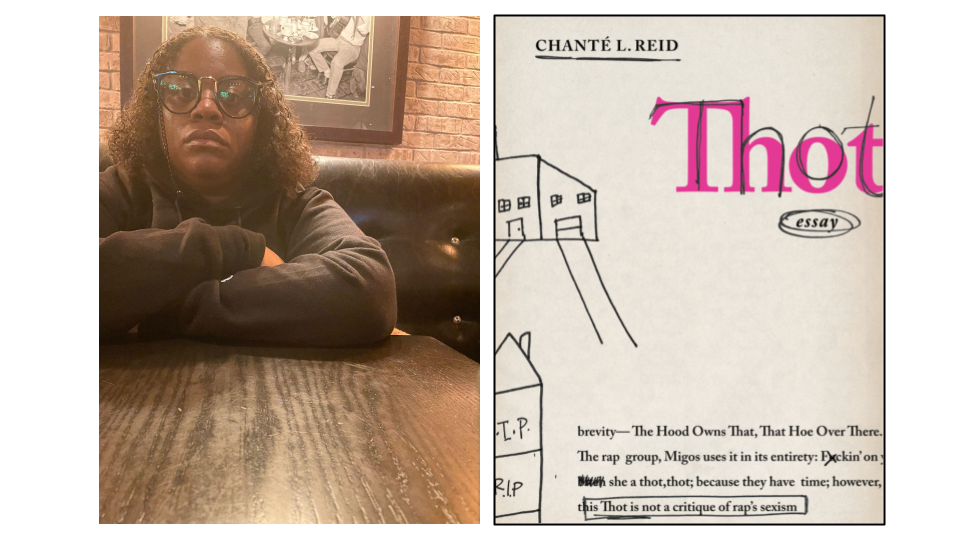

Chanté L. Reid’s Thot sets fires—both the kind started by a molotov, bent to burn down hierarchies, and the kind we huddle around for warmth and story. In an enthralling mix of forms, Reid’s book-length essay performs a highwire feat of textual experimentation in service of getting as close as possible to the forcibly grounding realities of racism, police violence, and alienation—but also of friendship and love. Through reported conversations, literary criticism of Toni Morrison’s Beloved, and an inability or refusal to choose the right words, Reid shows that the most searing of critique comes from a place of care.

Kyle Francis Williams: This book is extremely indebted to Beloved by Toni Morrison, so to start I wanted to ask, Why Beloved?

Chanté L. Reid: There are scenes in Beloved that have never left me, especially Sethe selling her body for the seven letters of “Beloved” on a tombstone. Even without the ability to read or write, this woman fought for a form of literacy and legibility. When I read that scene, it resonated with me as both a writer and as a Black woman: There is a fight for legibility and voice. At the end of the day, right, these are just letters, and I couldn’t figure out what made letters important, or why I liked writing anyway.

Was part of the investigation of this book figuring out why you wanted to write in the first place?

Absolutely. When you read a book like Beloved, it’s like, well, why am I even bothering?

In the book, Baby Suggs says something like, “1872 and white folks still on the loose.” Toni Morrison wrote that line in 1991. I have experienced the last thirty years and I have to ask myself, Why am I doing this? I don’t know that I have an answer to that.

There are other books too—Anne Carson, M. NorbeSe Philip. Did it feel communal in some way?

It did feel communal. I wanted in Thot to do away with tokenism, and to be in conversation with many voices, both established voices who write and my friends who don’t. We’re all thinking about these things. We’re all talking about these things. If we aren’t already all in this conversation together, I want to be. Conversation is so beautiful; it’s the poetry of call and response. Texts and people, they’re not dead things. They are alive and talk back to you as you talk to them. By having all those voices, I wanted to see if I could create a project that could give others the feeling I have while reading multiple things, talking to multiple people, at the same time.

Do you feel like polyphony is something you always strive for?

For right now, yes. With this project and the upcoming one. My whole life, I’ve always been around multiple voices. New York City is not a quiet place. But the last few years—with the pandemic and being in Massachusetts—I have been in a quiet place, so I have been working on some new things that are less polyphonic. That almost makes me sad, but it’s exciting for me to see what happens when I don’t have noise around me. Good noise. To be clear, I think noise is a good word.

You do the polyphony so well in this book, especially with the conversations with friends we get more and more of as the book goes on. Some of those are gut-wrenching, amazingly well written. Are those transcripts?

They’re not transcripts. Not really. They’re based on real conversations, but a lot has been invented or collapsed or composited. I showed the first conversation to my mother and she said she could remember parts. I added and took away. The reader doesn’t need to know that my mother asked me to pick up groceries, right? That wasn’t important.

And then so much of conversation happens without words. I had to translate gesture into language—and that’s really where I got to be an artist. That’s what I hope to do, and what I hope I did.

It is. . . so brave that you showed that to your mom.

Just the first page.

Did you show the conversations to Leo and Amanda as well?

Well, Leo is based off of multiple friends, more as a composite. Of course, now my friends are all trying to figure out which one of them Leo is. I’ve shown a couple of the conversations to people that Leo could possibly be based on. The character of Leo—well, this is published as an essay, so I can’t really say “character”—the voice of Leo is something I was the most afraid of, but also really enjoyed writing. It’s interesting to me that my friends and I grew up in an environment where it felt like we were presented with two choices: to be a cop, or . . . you know, not a cop. In that way, it felt like a risk to say not only that I know a cop but am friends with a cop, but I’m also asking: Why? Why are you a cop? And then, what is the consequence of that for Chanté Reid? Not the voice in the book Chanté Reid, but the person Chanté Reid, who never really believed this book would be a reality. But I have to write as though no one will ever read it, because that is the only way the words get on the page.

You just mentioned how this is published as an essay. I want to ask you about that.

My editor at Sarabande called me at some point to talk about this question of genre, of what I wanted to call this thing. After tossing a few ideas back and forth, the only thing that made sense to both of us was “essay.” The book is making an argument, and trying to prove that argument. But at the same time, genre—like gender—those categories aren’t fixed. It’s all writing. In many ways, Leo is a character, but that does not take away from the argument being made, the conversation attempting to be had. “Character” is an element of fiction that I transferred over to the essay. I’m not the first and I won’t be the last person to do this. But it was important to me that the book was just seen as writing, first.

At some point did you consider “poetry”? The way the text moves on the page looks quite a bit like poetry.

That one was the most scary to me. I’m a fiction writer. I don’t think I’m trained enough to call this poetry, but that might come from my anxiety about and fear of poets.

I do want to ask you about that textual movement; was it like searching for the right word, or an admission that none of the words are quite right?

The book is looking for the right word while knowing that none of the words are right. It also moves like thought moves. You ask yourself, Is that the right word? But there is no right word for this. There is no best option. The way thought moves is indecision, hesitancy, contradiction . . .

I love the phrase “moving like thought moves.” It’s so much fun to read that kind of indecision—though I don’t know how you would feel about me calling this book “fun.”

But that is important. Sometimes I would send this to people and they would say it was funny, and I would say that was great. Then other people would say it was incredibly tragic and sad, and I would say that was great too. Because life is both. But I also worried about making too many jokes. I want to take things seriously, because these are serious things I’m writing about, but life is so funny, so ridiculous, and so bizarre—and the more bizarre I made the book, the more the book looked like real life. And that’s also funny to me. And that’s also sad to me. Duality, bruh.

You write in the book, “Language used only ever with love.” Could you say more about that?

Sometimes, I can find myself forgetting that the reason I write is because I love to do it. I wouldn’t write if I didn’t love to. And then the reason I pick up the phone and let messages interrupt me is because I love the people I’m talking to, and I love the place I’m from, the Bronx, even when other people don’t. I’m not drawing it as a critique, or not only critique. There can be critique in love. In fact, there is so much critique in love. And there is so much love in critique. It was important for me to remember that I was writing this because I love these people and I love this place and I love writing. It’s that fight for love.

I might ask, Why am I doing this? And I might answer, Because I love it. Is that enough? Absolutely.

You said earlier, “Translating gesture into language.” I’m still thinking about it because there is this really interesting quality to this book in that the body is not at the center of things. The body is extremely present on that first page, but then it is mostly voice. Where do you think the place of the body is, in that case?

I think, a lot of the time, we see cause and effect based on bodies, as though the consequences of an action only affect a body. It’s like I’m trying to say that sticks and stones may break my bones but words will hurt forever. Isn’t that how it goes? And I don’t think bodies are as reliable as we assume them to be. My own body is not as reliable as I want it to be, and at those times when it has been least reliable, I have still had voice. I have spent most of my life physically impaired for one reason or another, and this is why discovering Beloved was to important to me, because I saw what the mind could do, what voice could do. What is a person beyond what we see? The body is so visible, it’s so present, but it’s just one layer of a person. It’s not even a huge layer. This goes again for the issue of gender when, at times, it seems cumbersome.

This is a funny story. I was at a rest stop and the W had fallen off of the women’s bathroom. This wasn’t an old rest stop—if it had been, I don’t think I would have found this interesting. It was a very fancy rest stop, very new and very clean, and the W had fallen off the women’s restroom, so the door just read “omen.” Of course I’m going in “omen.” I’m more of an omen.

But, translating gesture into language: What could I do without relying on my unreliable body, or anyone else’s? When thinking about the epicenter of this text—which is, of course, police brutality—so much of that conversation has been about the effect that violence has on the body, but when that violence happens it affects others in ways we can’t even talk about or see, because we’re checking our bodies, and there are no wounds. So what are we so upset about? But, of course, there are non-physical wounds. There is just no language for that kind of wound, because the body is safe. People make this assumption that because the body is safe, everything should be okay. But our voices are affected.

So what does it mean to have a voice affected?

For example, I lost my ability to code switch in the pandemic, because I was only talking to my partner, Amanda, and my dog, Icebox. And we had developed a language of references based on whatever we three were doing in isolation for all those months. Dogs are all gesture. We sit there and make up words for the things dogs are doing. This is my first pet. I love this dog. I didn’t think she would make this interview, but I translate gesture into language all the time for her.

I would actually mark losing my ability to code switch as a positive loss, because I don’t know why I was doing it in the first place. Code switching is useful—it’s a tool we have had to use as people—but I’m not sure it’s something I want to keep using or to reaffirm or to promote. I teach English, standardized English, but I don’t know how important standardization is. The first weapon formed against another human being was language. I spent my life trying to learn how to defend myself against that weapon. When I realized how much work I was putting into that, I realized how much I was losing. Why am I doing this extra layer of work? It’s just a conversation. And I didn’t want to keep doing that extra layer of work because I saw I had survived all those months without it.

There’s an interesting tension in this book between—let’s call her—the character of Chanté Reid and community. There are a few instances where someone is critiquing the character of Chanté Reid for using, like, academic language, or telling a story about Ernest Hemingway, which brings up the question for me of what insider knowledge looks like and is. When you’re trying to navigate that tension between the “I” and the community, what are you considering?

The audience is inside of the book. That writing move I make there, I’m not going to call it cowardly, but I am anticipating possible critiques. It was about taking a second for myself to reflect on what I was saying. My relationship to the Bronx is not one of exception. I think I am a member of a community and a place that, by many, has been deemed unexceptional, but we’ve never lost ourselves in that. I see memes about the Bronx all the time, and they’re funny and we share them. We don’t mind telling jokes about ourselves, because we know our reputation. And I’m not trying to shy away from that reputation or trying to say I’m different—I’m not a token—I’m just saying that we’re all worthy of love. That the language is worthy of love, and the people are worthy of love. I don’t want to make myself exceptional. I want the community and place that I am from to seem as exceptional to others as I find it.

Right. That makes perfect sense, and I identify with so much of what you’re saying, thinking about my own community and my relationship to it now that I’m in . . . Academia? I guess? If an MFA even counts.

Well that’s the other thing—that’s the big joke of it. Is that six-word Ernest Hemingway story really that academic? “For sale: baby shoes, never worn.” It’s not so scary. We do this everyday. We talk. We talk in metaphor. The big joke to me is, What is academic language? That story isn’t allusive. None of it is allusive if you want to know it. I want to make a joke about hierarchy, about what is deemed high or low art. Mixing it all together and seeing what we get.

When you went off to get your degree, was there ever a nervousness that you were leaving that community at home?

There was up until one point, while discussing Valeria Luiselli’s The Story of My Teeth. We started reading that maybe two months into my first semester, so I was still getting used to things like calling the instructor by their first name or having only six people in a classroom. It felt like the name “Brown” should be causing me anxiety. But when we were reading the book, one of my peers said that it was cultural appropriation. That factory workers could write their own books. That’s when the whole thing stopped being so scary to me, because I was just like, Wow. It’s very hard to work and do anything else at the same time. There is knowledge and experience I have that is important and that needs to be added to these conversations.

My experience is of coming from two blue collar workers who did not have time for much else but blue collar work, and knowing that they had dreams, but that they also had children, and had to go to work. Again, not thinking myself exceptional, I come from people who are hard workers and have never had the opportunity to go the places I’ve gotten to go. My parents were geniuses. Just because they put on a uniform everyday didn’t mean they weren’t. And it was just so funny having that experience, being a part of the community that I am a part of, and then seeing Valeria Luiselli—someone who was actually trying to talk about work—be critiqued because they weren’t talking about it from their personal experience. What are we even defining as personal experience?

That is something that comes up in the book, when the character of Chanté Reid is talking to someone about the “accessibility” of certain texts. And that is a word that I definitely struggle with. Why can’t the working class have an avant-garde?

That’s it exactly. When someone’s using the word “accessible,” I ask, Accessible to whom? Who is making those distinctions? In the book, I stayed away from conversations with clear power dynamics, with professors or with students, because I was more interested in showing how one talks to one’s equals, or one’s peers. The question remains, What is authority? Who has it? Who has the right to it?

I see the book as a kind of fishbowl. I’ve started going to a lot of these. Two people sit in the center of an audience and have a conversation; the audience gets to listen to that private conversation as a community. Who are you talking to? I’m talking to me. And “me” is so many things.

I remember a line from the book, where an interlocutor criticizes your work by saying, “I would never write anything my sister couldn’t read.” And it’s like, Why do you think your sister can’t read?

Exactly. Have a little faith in your sister. Yes, write towards your sister. Write towards yourself. You should consider your sister to be part of yourself. That’s who I’m writing to, that’s who I make work accessible for: It’s me. All of me.

Kyle Francis Williams is a writer living in Brooklyn and Austin. He is an MFA Candidate at UT Austin’s Michener Center and Interviews Editor for Full Stop. His fiction has appeared in A Public Space, Southern Humanities Review, and Epiphany, and is forthcoming from Southampton Review and Joyland. He is on Twitter @kylefwill.

This post may contain affiliate links.