This essay was originally published in the Full Stop Quarterly “Cynicism” issue (Fall 2022). Subscribe at our Patreon page to get access to this and future issues, also available for purchase here. Your support makes it possible for us to publish work like this.

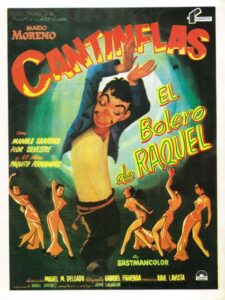

It’s 1957, and, like most of Mexico, Cantinflas needs money. Once content with living hand-to-mouth, the death of his best friend suddenly leaves him in charge of raising his godson. In search of opportunity, he pursues an education while taking on odd jobs, none of which he’s qualified for. He replaces his compadre as a mason by presenting the dead man’s own words as proof of his trustworthiness; the wall he builds is rickety, crooked, and draws the bosses’ ire. Cantinflas defends himself with his novel art-history knowledge: It’s modernism, sir, and the askew doorframe? Gothic, or Romantic.

The boss serves Cantinflas his last paycheck. When Cantinflas’s charge questions his methods, he replies: they need more ignorance.

*

Mario Moreno, stage name Cantinflas, was, and, despite passing away in 1993, is México’s premier comedian. His films have enjoyed several lifetimes of reruns on Televisa, the largest and longest-standing of the nation’s few open air television channels. His presence in Mexican culture is so distinctive yet ubiquitous that he’s denominated the very concept of talking in circles: cantinflear, verb, to speak in an incongruent manner, saying nothing of substance.

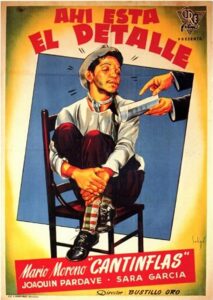

Even Cantinflas’s nonsensical name is a reflection of the working-class origins that would guide the course of his acting career. Like his own characters, Moreno worked a disparate curriculum of jobs. Shoeshine, chemist, boxer, taxi driver, bullfighter, military typist—nothing stuck except the circus. In a late-life interview, Moreno confessed to the meaninglessness of Cantinflas, having coined it to hide his career from his parents, who considered the entertainment business shameful. After learning to dance, “Cantinflas,” already a complete character sporting dirty overalls and a rope for a belt, became an acrobat and comedian. Working on the hard streets of Tepito, a legendarily tough borough of México City, Cantinflas crashed his way into the film industry the same way all his characters would: wit, improvisation, and quick words. By 1936 he’d debuted in the background of the largely unsuccessful Don’t Fool Yourself, Dear, and in 1939 he leaped to his first protagonist film, You’re Missing the Point, the title of which would rapidly become one of his many catchphrases.

Though he may have picked up the act of comedy from his early career as a circus hand, Cantinflas’s early work in cinema had little in the way of face paint and pratfalls. In You’re Missing the Point, Cantinflas is faced with the difficulties of poverty: His girlfriend, a housemaid who lets him steal food out of her employer’s fridge, tasks him with killing his boss’ rabid dog, “Bobby.” Rather than go hungry, Cantinflas shoots the dog. The situation is only humorous for his ability to crack cynical jokes about it.

As You’re Missing the Point develops, Cantinflas’s inability to communicate that “Bobby” is distinct from inheritance-spat murder victim Bobby results in his near imprisonment. This is an early incarnation of the class conflict at the center of Cantinflas’s oeuvre: educated language as a failure point. What would change is his characters’ ability to walk the fault line in their favor. A few years later, in movies like Carnival in the Tropics and Gran Hotel, he’d be playing a near inversion of his first protagonist: characters that know what they want, understand that affording it is impossible, and hatch intricate plans to get the money they need anyhow. Cantinflas enjoys his vacation to the fullest first and worries about paying back the lender who financed his fancies later; he’s confused with a foreign duke and rides the benefits to their end.

Despite all this, Cantinflas is never portrayed as an “antihero” moved by greed and selfishness. All he does is climb his way up the ladder of a rapidly rebuilding country, whose developing economy had promised exactly that: a good life for those who can make it.

*

To understand Cantinflas is to understand the latter half of twentieth century México: so claims Gregorio Luke, former Director of LA’s Museum of Latin American Art. While United States cinema boomed into the golden age of the 1920s, México struggled to rebuild in the ruins of civil war. Twenty years after the war’s end, the nation’s illiteracy rate still sat at 70 percent. However, infrastructure had caught up enough for México to develop its own, crucial film industry.

The magic of mass media: Easily reproducible, undemanding of literacy, it can reach those most isolated, with little discrimination. From the ‘20s to the ‘40s, México went from being the first Spanish-speaking country to introduce television (and color television) to a twenty-years delayed golden age of cinema. It was the perfect storm for Mario Moreno’s verbal genius to take over the nation.

In the tradition of the great early-century American comedians like Charlie Chaplin, Mario Moreno plays more or less the same character in every movie: Cantinflas is a working-class easygoer, with the gift of gab and the singular modus operandi of talking his way into and out of every hairy situation. He is the sum of the aspirations of a nation of laborers that have been denied access to basic education: the dream that one can, indeed, work smarter, not harder.

Cantinflas comes to a peak in 1957’s El Bolero de Raquel. Rather than climbing the ranks, his newfound education enables him to run ever-larger circles around his employers. It’s not that he is unambitious, much less simple: No man with such an ability for neologisms could ever be described that way. It’s rather that he understands that no talent in the world, or at least in México, will ever make the worker a boss. Rather than aim for the impossible, Cantinflas works as little as possible.

In this manner, Cantinflas is the inheritor of millennia of cynicism, a philosophy “pioneered” by the barrel-living, work-scoffing Diogenes. There is, however, a distinctly haute spin on Diogenes in the modern era. Academic tradition has enshrined him as a great thinker, a sort of paragon of naysaying, in an ironic twist on his refusal to be academicized: No writings penned by Diogenes himself have survived, and he exists primarily thanks to the memoirs of the philosophers he owned.

Modern cynicism is the privilege of academia. A good cynic writes in thick, indigestible prose, gets published by way of an instant Great Novel, and categorically declines to watch television unless it’s to mock it. Diogenes’s barrel is a symbol of enlightenment only retroactively; today’s houseless are lazy bums, and if they’re dissatisfied with society, they should just work harder.

Starting in the 1940s, America was in great need of reinforcing this idea. A snappy war economy required a workforce that refused to listen to itself; questioning where and why the war was going was treason, not just to the nation, but to your fellow worker. Thus grew the artificial divide between thinker and laborer, a divide which found its way through México’s geographical and socioeconomic entanglements to root itself into the labor ethics of a “developing” economy. Take a look at 1951’s ¡Ay, amor, cómo me has puesto!, starring the equally enduring actor-singer-comedian Tin Tan: A poor baker earns the approval of his lover’s middle-class family. His relative command of language acts only in the service of highlighting what a presentable, hardworking young man he is. He can earn middle-classness.

Cantinflas’s opus is a distinctly Mexican testament against the myth of hard work. By appropriating the florid language ascribed to academia, crafting with it sentences both meaningless and slippery, Cantinflas manages to raise his godson, and enchant the titular Raquel. In an exploitative society, the great victory of cynicism is not to transcend, but to avoid lending your labor to be transcended upon.

*

Like Diogenes before him, of course, Cantinflas transcended anyway. He’s the first in a still too-short line of Mexican television cynics, a title inherited by El Chavo del Ocho’s Don Ramón, and, as Televisa’s national monopoly on attention thinned out with the introduction of the internet, gone up in smoke.

Entangled as it is with the US’s economy, México has again inherited American modes of communication. Now is the era of abject sincerity: diputado candidates picking fights with replyguys, blue checkmarks with pretentions of journalism who can’t be bothered to investigate slang, a daily parade of low-effort digs at the political villain du jour. Hyper-speed communication has roped us all into the Spectacle: Dropping the perfect pithy line about the world’s ever-worsening conditions feels like contributing to slowing down civilizational degradation, even when all we’re doing is spitting in the wind. It’s daily bread. It’s work.

Revisiting Cantinflas today is a reminder of what true cynicism looks like. Maybe the most shocking part is what a kind character he is. After all, the modern perma-cancelled Netflix special comedian is callous, cruel, detached from the state of the working class. It’s the coup de grace of a media class that thrives on scandal: The conviction that workers should be cynical about each other.

The answer to this cannot be aspirations of abstract, doe-eyed hope, at least not by itself. A good, true Diogenic dig serves to delineate the exploiter from the exploited. Through his refusal to settle anywhere and do a good job, Cantinflas is a happy man. Cynicism exists for the oppressed to defeat their oppressor.

Julia Norza is interested in borders: between countries, genders and minds. First-hand witnesses have described her work being featured in WEBTOON, An Injustice! Magazine, and Deconreconstruction.

This post may contain affiliate links.