This essay was originally published in the Full Stop Quarterly “Cynicism” issue (Fall 2022). Subscribe at our Patreon page to get access to this and future issues, also available for purchase here. Your support makes it possible for us to publish work like this.

Like so many others, my love of art bloomed while in the throes of a lonely adolescence. Social isolation prompted me to withdraw into myself, hard, as did the dissolution of my religious conviction. I began to seek a silent communion of sorts with the outside world: to observe and contemplate while keeping participation to a minimum. Immersing myself in music, literature, and films provided me with this one-sided communion, elevating my interiority while scrubbing me of my specificity. I grew to regard myself not as a single subject, but a vessel for that lofty, insoluble thing known as the human condition (if not articulated in those exact words). And so I nurtured my aesthetic sensibility, wielding it against the stakes imposed by reality. Through Anna Karenina, I became well-acquainted with passion, jealousy, and pride; through Philip Glass’s compositions, I discovered the value of a slow burn; through Jonas Mekas’s films, I absorbed the subtle but abundant beauty of the quotidian; so on, so forth. All of this I learned from the confines of my childhood bedroom.

Active participation, I assumed, would come later. It did, when I was thrust into adulthood and tasked with creating a life for myself. I discovered that I was ill-equipped; my armor was ineffectual, built for hypotheticals and abstractions. The insights I had gleaned from art dissipated in the presence of the real deal; love, heartbreak, failure, and hypocrisy struck me with the full force of novelty. More disorienting still were the low-level, diffuse indignities and banalities of day-to-day existence. I anticipated the highs and lows, but not the ambivalence that often accompanies them. So when people told me I was mature for my age, I knew it was untrue. I knew that my precociousness was a covert form of naivety: I had wanted to experience beauty, emotion, and sensuality from a safe distance. More acutely, I wanted salvation without the fall; I wanted art to save me from life. In the absence of religion, I looked to art for guidance, solace, and a sense of purpose.

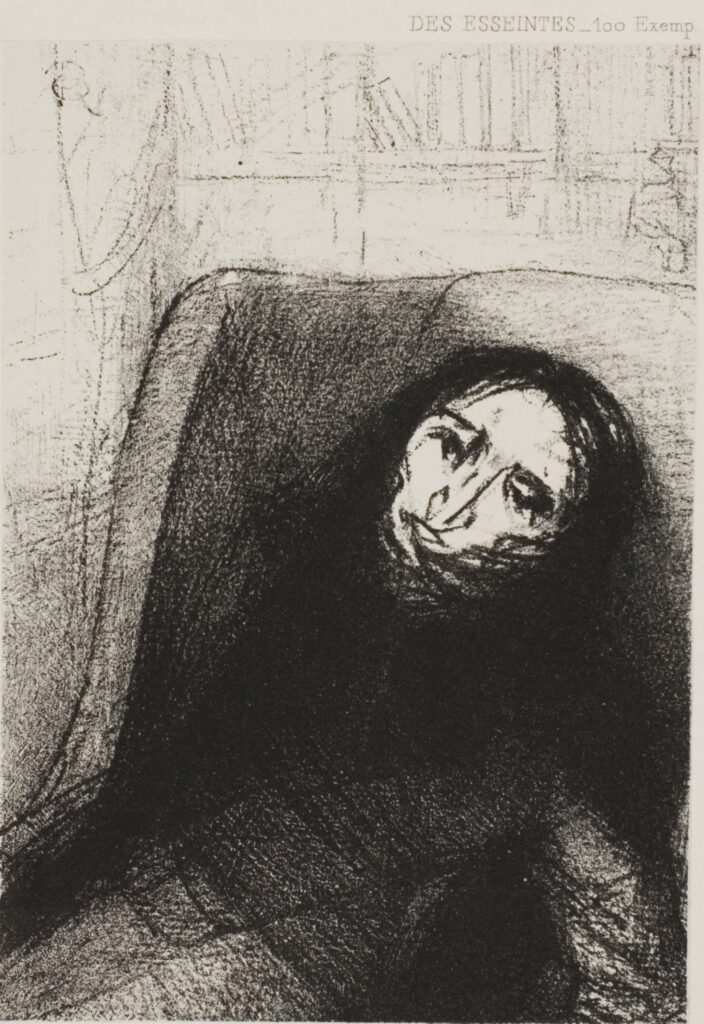

This mindset is common enough among the young and bookish. It is less common for an adult to disavow life and retreat into art. Jean des Esseintes, the main and sole character of Joris-Karl Huysmans’s infamous novel Against Nature (1884), does exactly this, removing himself from society by transforming an estate on the outskirts of Paris into a solitary fortress of aesthetic revelry. His exodus is driven by vehement misanthropy—by the crude and petty pursuits people preoccupy themselves with — by their inexorable hypocrisy and greed and delusion. Although Des Esseintes critiques human behavior, his contempt is fueled not by moral indignation but distaste; other people categorically affront his delicate sensibilities. Lack of originality and insight sends him into an inconsolable rage.

As far as Des Esseintes is concerned, he has done everything in his power to resist misanthropy, succumbing to it only after exhausting all alternative options. He tried to find fellowship with others, observing the customs and values of different social groups and classes; he dabbled in religion, scholarship, social climbing, and romance. Hedonism proved to be his most enduring pursuit, yielding the most consistent rewards. Over the course of many years, he sought out increasingly perverse, idiosyncratic pleasures in sordid corners of Paris.

After becoming a connoisseur of Parisian brothels, Des Esseintes took to soliciting women from the theater and circus, drawn to their expertise in performance. In one striking recollection, he propositioned a young ventriloquist, asking her to give voice to the Chimera and the Sphinx statues he brought into his bedroom. As she recited Flaubert’s dialogue, lying still next to Des Esseintes, a fire crackled and hissed, casting the statues in an amber glow. The scene was a success: Des Esseintes fell into rapture, utterly transported by his private theatrical production and transfixed by his mistress insofar as she contributed to his aesthetic sensation.

This escapade is paradigmatic of Des Esseintes’s specific brand of perversion: thorough manipulation of his surroundings until he is sufficiently convinced that the world is anew, created in his distinct vision. All fantasies are about control, amongst other things, but Des Esseintes’s are particularly chimeric; he is unmoved by authenticity, and, as such, intimacy. But eventually even hedonism fails him, and his carnal adventures sour into repetitive empty gestures. His body recoils from over-indulgence and shuts down, rendering him sexually impotent.

Des Esseintes deduces that people are the common denominator in his troubles, in the waning potency of debauchery. Others spoil his pleasure by failing to grasp its depth and quality. The pleasures of others, conversely, are too crass; he is repelled by the men who hole up in taverns, drinking themselves into a stupor while sloppily flirting with barmaids; he derides their sexual “conquests,” which are not conquests at all but transactions in which men and women play studied roles. He is equally repelled by his supposed peers, aristocrats and men-of-letters—the aristocrats are boring; the men-of-letters, pretentious opportunists.

After discerning that nobody takes aesthetics as seriously as himself, Des Esseintes seeks existential refuge in solitude. In a suburban estate designed to his eccentric preferences, he continues to indulge in a plethora of sensual experiences, but now, he enjoys them within a controlled environment. Des Esseintes is fastidious in his efforts to seal himself off from society: He takes only two servants from his previous home and requires that they be silent, issuing them slippers and oiling the door hinges so that their movements are imperceptible. Otherwise, he accepts no visitors (not that he was particularly popular anyways). This hermetic existence provides him with total freedom to follow his bliss, unobstructed, but not without cost: His health further deteriorates from lack of social and physical activity, exacerbating his hypochondria.

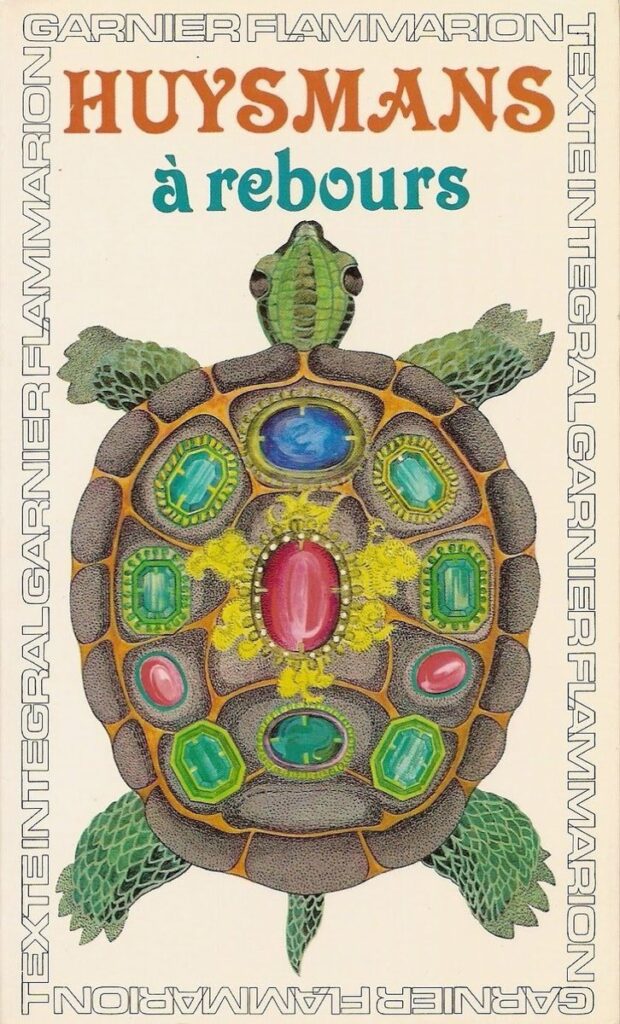

Much of the book is dedicated to interior design, detailing the extreme measures Des Esseintes takes in order to form a satisfactory living space—one which stimulates all five senses, catalyzing flights of imagination. In one of the most absurd scenes, Des Esseintes purchases a turtle to resolve a color palette dilemma, surmising that the swampy green of the turtle’s roving shell would offset his iridescent oriental rug. This plan fails, so he course-corrects, deciding instead to attenuate the rug’s shine by contrast of an even more brilliant object; he has his tortoise glazed with gold and embellished with precious gemstones. This plan succeeds, providing the desired contrast, but the success is short-lived—literally. The turtle collapses under the weight of its adornments. The metaphor at work here is plain: Nature cannot bear the pressure of artifice. This message is less humanist (man conquers nature through his distinct intelligence) than pessimistic (nature disappoints for it cannot accommodate man’s wildest dreams).

Aside from fussing with decor, he spends most of his time contemplating and critiquing art. Long chapters are dedicated to Des Esseintes pontificating about his aesthetic preferences, particularly in regard to literature. His tastes run counter to the mainstream opinions of his day: He dismisses the Latin authors of the “Golden Age” and the French Romanticists; he embraces the “Silver Age” Latin authors as well as early Christian texts, Realism, the nascent Symbolist movement, and the work of Catholic mystics. He essentially rejects art that contains “moralizing inanities” and attempts to neutralize the cruelties of life. (Naturally, his favorite philosopher is Schopenhauer, whose theory of Pessimism “saves you from disillusionment by teaching you to expect as little as possible.”)

Des Esseintes’s survey of Latin and French literature reveals a breadth of artistic knowledge and a considered point of view. His expertise is impressive—slightly less so when accounting for his social position as a wealthy aristocrat. He possesses the resources and time to access and contemplate art; this is a privilege but also, as Des Esseintes laments, a curse. During one of his more philosophical meditations, he equates the level of suffering of the worker with that of the aristocrat: The worker suffers from hard labor while the aristocrat suffers from ennui. Art buttresses Des Esseintes from discontentment but only temporarily; he cannot keep life out. Memories interrupt his aesthetic reveries with bouts of melancholia swiftly following suit. His ennui manifests in physical symptoms, and by the end of the book, his health is in dire condition. A doctor prescribes re-immersion into society, warning Des Esseintes that if he doesn’t start acting like a normal person, he will probably die. Des Esseintes reluctantly agrees to reenter the social world and compares his predicament to that of a non-believer attempting to cultivate religious faith: “He would have liked to force himself to possess the faith, to glue it down as soon as he had it, to fasten it with clamps to his soul, in short to protect it against all those reflections that tend to shake and dislodge it.”

In many respects, Des Esseintes is a despicable—if often comic—figure. Amoral, apolitical, and antisocial, he repudiates love, empathy, and respect. But he is not a mere hedonist, and while his attitude towards humanity is textbook cynicism, his earnestness with regard to art and aesthetics is distinctly uncynical; unlike other dilettantes, dandies, and men-of-letters, he has relinquished the desire to use art as a pathway to social distinction. He values art as an end in itself, not as a means to bolster his status or construct a public persona. Des Esseintes’s motives are pure—or, interpreted another way, mad. He believes in art, fully and blindly, conveying his “genuine fellow-feeling for those who were shut up in religious houses.” This perceived kinship extends beyond the impulse to self-isolate. He approaches aesthetics with a religious-like devotion; transcendence is his preeminent aim:

He wanted, in short, a work of art both for what it was in itself and for what it allowed him to bestow on it; he wanted to go along with it and on it, as if supported by a friend or carried by a vehicle, into a sphere where sublimated sensations would arouse within him an unexpected commotion, the causes of which he would strive patiently and even vainly to analyse.

For Des Esseintes, salvation is found, if only temporarily, through exquisite contemplation. He treats the refinement of his aesthetic sensibility as a quasi-spiritual process of purification.

This solipsistic conception of art is appalling, particularly clashing with contemporary sensibilities. Understandably so. Art brings people together; it engenders conversation and collaboration. To shut one’s self off in a methodically managed pleasure dome is to deny an integral part of art’s value. But during a time in which art and commerce, aesthetics and identity, are enmeshed to the point of inextricability, Des Esseintes’s utopic “life of the mind” experiment is something of a salve. Though it founders, his imaginative capacity awes. Today, we call upon art to help solve political ills and, ultimately, transform the world into a better place. Then we watch, dull-eyed and disillusioned, as the awareness that politically-charged art raises does not translate into meaningful change—often translating into lucrative investments for the ultra-wealthy or fodder for self-righteous posturing instead. Des Esseintes asks nothing of art. Or rather, he does not expect it to alter external circumstances. He dedicates himself to it completely anyways, exercising faith in its palliative effects. It is this faith in art’s intrinsic value that is so refreshing: no justifications necessary.

But given that faith is antithetical to cynicism, it is confounding that Des Esseintes holds faith in art, but not humanity. The two are inextricably linked. (Need I say that art is made by people and draws from human experience?) Sure, art is human experience sublimated—raw material kneaded into a separate being, a portal to a richer mode of existence—but it is still born from a person’s experience of reality, regardless of how fantastical the finished product. Like my adolescent self, Des Esseintes seeks to bypass the crude parts of life and skip ahead to a state of steady inspiration and revelation. This proves impossible, and the momentum he has directed towards upholding this extreme, contradictory stance culminates in implosion. Aesthetic immersion could not save Des Esseintes, just like it could not save me.

Upon its release, Against Nature was met with a polarizing response, scandalizing and electrifying in turn. It continues to provoke both responses (if scandalizing in a different way); author Michel Houellebecq and punk singer Richard Hell both cite the book as a major source of inspiration. Hell has even drawn parallels between the decadence of Des Esseintes and the punk ethos. The book’s author, Joris Karl-Huysmans, lived a relatively mild life himself; he wasn’t a debauched aristocrat but a civil servant, who worked steadily for the French ministry for thirty-two years. He was, however, an aesthete who grappled with intense spells of melancholia. And like Des Esseintes, he longed to “possess faith.” So he did, returning to the Catholic church after Against Nature’s publication. Art wasn’t enough; he adopted a more collective and structured form of belief. Yet, he continued to write novels, to build new worlds that reality can’t accommodate. He retreated into art, then emerged into the world, again and again—a dance that may not save but certainly enriches, merging with the undulations of existence and, dare I say, nature.

Caroline Reagan reads and writes in New York.

This post may contain affiliate links.