[Duke University Press; 2022]

What is a gathering? How does the poem gather? How does the poem bring together or apart?

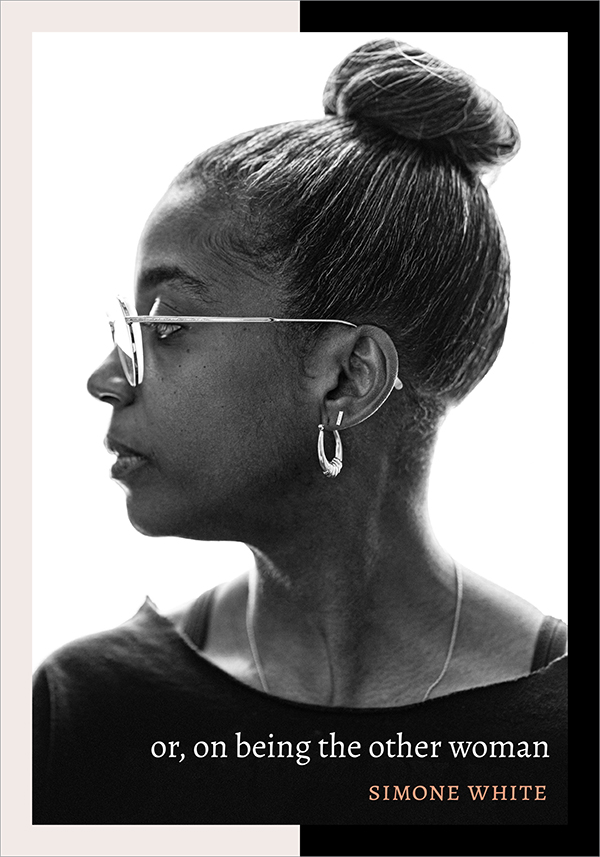

“We go to the room for stories, nestled / lumped or thrown together we and things,” Simone White writes in the opening of her book-length poem or, on being the other woman. The collection, published last month by Duke University Press, is a precisely and powerfully wielded account of the self—as a Black woman, mother, theorist, and lover—who emerges in the tension between her own singularity and the relational nature of her becoming.

The poem starts in the house, where White and her son find themselves amidst an atmosphere of everyday things; objects that have accumulated loosely and persistently around them. White maintains a powerful ambivalence towards these things: a love of things, an interest in thingliness, and at the same time anxiety about their persistence and disorder. “i have things a sense of things that belong to me that i have clung to,” she writes early on. Her language documents the ways things can be joined together: Words like “nestled,” “lumped,” “thrown together,” “heaped,” and “piled” dot the text as forms of gathering the lost “devices,” “empty water glasses,” and “unmatched socks” that populate the home she shares with her son. Living with others is especially messy, and difficult for White whose need for “certain kinds of privacy, tidiness” (as if they are the same) compels her into continual cycles of arranging and rearranging. She describes her son’s regard for their home as “an undifferentiated space in which to pile expensive junk.” To arrange things within the home becomes not just a domestic task, but a way of articulating a field of meaning. “Effective means of housekeeping categorically interest me,” White writes in a line that exemplifies the blending of abstraction and “the low” characteristic of her project. The house is less a noun than an activity as it is sustained through these cycles of messing and unmessing, its being “kept” together and its coming apart.

The poem is like the house: a field of meaning articulated in the arrangements of its materials. White’s language is distinctly physical, its materiality made prominent in the play with lettering and the distinctive structuring of her logic, or “compositional attitude.” She writes: “in my guise as woman work and insomnia / rumble through they are girders money / worries girding my whole body such job interviews / sayjng intoleraB / le / kinds of nothing about how all of it came / to pass.” In moments like these, lines become like architectonic structures as unfamiliar line breaks, capitalization, and syntax bring attention to the poem’s distinctive mechanics. Its logic feels not just written, but constructed, or rather, deconstructed. As in the house, those processes of coming together and apart converge in the poem, its “constructed unpile.”

or, on being the other woman does not move in a straight line. Its action is multidirectional and cumulative, cultivated in the relational dynamic between its parts. Meaning, or “the field articulated as has been,” White claims, as a linear and determined trajectory, fails to account for what she calls the “quantum wilderness” of being alive. That is, conventional narrative does not comprehensively articulate the multidimensional nature of being alive, its waywardness and interrelational chaos. “The poem’s time,” in contrast to the time of linear narrative, White writes, is “both long and never, the poem surrounds or bends or encircles the characteristic of being one.”

It’s in this sense of nonlinear movement that the collection resembles White’s characterization of trap music. “i think of an engulfing curve,” she writes of Mike WiLL’s trap base, “nondirectional and therefore multidimensional, large enough to disturb conceptions of forward motion.” Like the poem, trap is not a straight line of meaning, but rather becomes a kind of textured wave in the multidimensional and interrelational signaling of its elements. In a question that could be equally applied to her own work, White asks of trap, “what happens when a linguistic field is generated by high energy signs across a flat plane of signification,” and answers, “there’s no need for logical progression or . . . ‘narrative.’”

For White, trap is inextricably linked to who she is. Her analysis of the genre, filled with the kind of conceptual ingenuity and linguistic play that characterizes the poem as a whole, begins to unveil the layers of ambivalence that characterize her relationship with herself as a Black woman. “I am the songs and they are me,” she writes, “although I do not make / them and cannot and the songs say they hate me, anyway, although I must and do love / them, and are even so, the truth of the surround.” Trap’s physical properties, the weave of bounce, voice, and rhythm, vibrate with a kind of undeniable human vulnerability difficult to pin down. Despite its employment of often misogynistic language, trap embodies the coextensive realities of survival, sex, and horror that make life as a Black body. “I have used this music, its metaphorical aliveness,” White explains, “as a proxy for the unbearable ways my body declares itself irrepressible or central to anything that is.”

White looks for a way out of herself, beyond the confines of her body, and the systems of oppression meant to control her. Her language makes stark the terms of survival in what she unmistakably describes as “(the economic / emotional and racial matrix that forms black women as persons who carry, fuck never / tire, and remain impoverished).” She describes an existence that persists despite forces of subjugation, erasure, and exploitation enacted on her by white patriarchal society, both structurally and personally. White seeks liberation from the confines of these terms, freedom from her own formation, from her body. “Men as they exist in their bodies are not the subject of my interest so i do not “rail / against” them,” she writes after her lover accuses her of just that, adding, “that is a misrepresentation of the whole of my aesthetic and phenomenological project / which involves taking up the vision i have been given of my own freedom / i have been given a vision of it, life beyond use.”

The early interest in the relationships between things in the home becomes transferred to the relative, and changing, position of people. The collection is interwoven into White’s relationships as a mother and lover to men, and documents the layered histories of her attachments. Her son, and an unnamed “you,” become the central figures of White’s attention as she continues to explore what it means to come together and apart, to be with and without.

From a young age, she describes a position of apartness: her “strangeness” as a child, and the pressure to conform to middle-class norms. “i had already been warned,” she writes, “i would affect the aggregation if i refused.” Her difference becomes a threat to the collective body of the status quo, or the “aggregation,” another kind of pile or gathering, from which White seeks freedom. In adulthood, at the “‘height of [her] [emotional] power,’” White finds herself again on the outside. “I call myself ethically to account for “dependency,” she writes. “I brought this term to describe a / quality of femininity from which I have broken, not by choice, yet broken absolutely, / anyway.”

As a young boy, her son is almost entirely dependent on her and their attachment is deep. White describes the “anxious detachment” she felt when survival made it necessary for her to work away from her infant son, the words she teaches him to call her near, and the loss of solitude, of privacy, that comes with having a child. White is certainly depended upon. What she has come to refuse is the infliction of dependency upon her by both structural and personal agents.

She draws from feminist poet Alice Notley in her conception of a new “spiritual and ethical position” of self-reliance based on the recognition of the other’s, even unconscious, will to control or subject her as a woman. White has become what she calls a “free radical,” having broken free from “the aggregate.” The toll of this liberation and its maintenance is not to be underestimated. “We are in a realm of absolute violence,” she writes. “not self-care / bald survivalism / i have been nearer to the gestures of survival than i would like.” Her independence is forged arduously, as work that is never separate from her body:

if i keep looking at the word independent i can see it surrounded by practices of sex work / it is always pussy that gives me value and this, fact of undeniable facticity, / must also enter my estimation of the state of my own excess. the forms my life takes / have berserk intensity. / dissolute facticity / whatever means i use to accomplish liberation will lead inevitably to the destruction of / someone’s marriage

The poem’s “you,” and the collection’s title, become clarified in this moment of reflection: He’s married. White ponders over the destructive consequences of the pursuit of personal freedom when she asks later on, “what is the difference between the figure that destroys and the figure that breaks away.” She discovers an inextricable link between the actions of being apart and being with. Even the pursuit of independence, of a kind of apartness, is achieved through intimacy, or at least, physical proximity. Its effects reverberate in a fabric of relations, impossible to escape from.

White continues to negotiate the play between proximity and distance in her relationship with her lover. The relationship is pained, filled with agonized waiting, self-questioning, and moments of profound connection. White describes a concomitance of profound intimacy (“a form of intimacy i / had not been taught to hope for”) and tormented distance in what she calls the “the possibly violent dance of being gathered as minimally / two.” She is particularly attuned to the way relationships are constituted by distance and difference, “the fundamental mag- / netism where two bodies do not touch.”

To be with includes the distance between constituent parts, in fact, requires it. But when does distance terminate the bond where “with” becomes “without”? When does the poem no longer hold together, or the house become unkept? White’s relationship with her lover ends in a reinterpretation of that distance, its turn, at least for him, from one that unites to one that alienates. “months spent agonizing and dumb,” White explains, “end suddenly in a text message that includes the / phrase ‘this weird distance between us’ wherein i learn of the distance as such.”

White becomes herself through these cycles of proximity and distance. “If i have anything like a materiality, see,” she writes, “i experience it in the discovery of how ‘distance’ means between us, and disturbs the thing i am, with all things.” Much like the poem itself, she finds herself within a field of relations that is sustained by the simultaneous activities of its breaking apart and coming together. She becomes as the poem becomes, not in a straight line but as a vibrant texture of relations. In the end, White achieves a stunning and important feat in the articulation of the material dynamics of being and the pursuit of freedom. or, on being the other woman pulses with the vitality of a woman who has made her own language for love.

Tess Michaelson is a writer, editor, and artist based in New York.

This post may contain affiliate links.