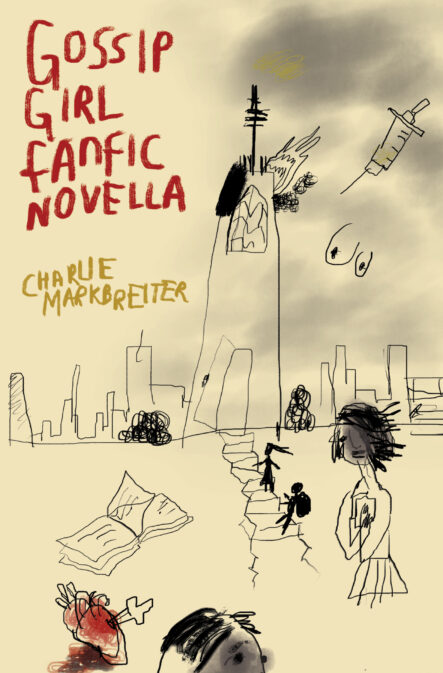

[Kenning Editions; 2022]

You don’t need to have seen Gossip Girl to imagine what it’s like. There is a crew of rich teens (who are sometimes drunk and sometimes in love and often miserable). There are their rich adult parents (who are sometimes drunk and sometimes in love and often miserable). There are a lot of pretty clothes and shots of New York. There are financial crimes and real estate deals and no real mention of politics (unless it’s one main character’s cousin, a senator, cheating on his wife with another main character). But it’s political in the way that many teen dramas are, indexing the currents of American culture in the era of its creation: Here are the good rich, here are the evil rich, here are the not-as-rich, the used-to-be-rich. Charlie Markbreiter’s excellent new book, Gossip Girl Fan Novella, turns that indexing on its head, interrogating the mutually constitutive relationship between culture and consumer.

Gossip Girl Fan Novella consists of three main threads: 1) fanfic of the original show, 2) the story of a trans man named Gordon working on Gossip Girl 3 in the near future, and 3) essayistic blocks covering fandom, trans politics, and celebrity culture in the twenty-first century. The book is wide-ranging in its interests. (Whether you are a fan of Gossip Girl or not, if you are the sort of person who enjoys chasing down citations, as I am, this is for you.) However, at its core, its concern is that of the original show: money.

In the fanfic sections, we find the same super-rich kids (Nate, Chuck, Serena, Blair), the rich-but-less-rich (Dan), and then those who actually have to work to survive (Vanessa and an original character, Dan’s friend Max). One of the first and most attention-grabbing revisions is that Nate (“The beautiful himbo. Bernie Madoff is his dad”) is recast as a trans boy. He’s only able to transition through his family’s wealth and status, since, “getting blockers in 1998 was impossible, not because the chemicals didn’t exist . . . but because trans people didn’t exist yet, at least not in the public eye.” In a section summarizing Jules Gill-Peterson’s Histories of the Transgender Child, Markbreiter reminds the reader that early experiments in childhood transition were “mediated by race and class, as is everything.” Gender plasticity was conceded to white children who could afford treatment; black children were misdiagnosed as schizophrenic. Like everyone in the Gossip-verse, though, Nate is oblivious to the privilege in this. “They say the thing about transitioning young is that you get to be not just normal but regular,” he thinks. Never mind that there is nothing regular about being able to transition young; never mind that, immediately after he thinks this, Nate literally transforms into his father.

The intersection of capital-N Normalcy and money suffuses the book. In the near-future sections, Gordon, who worked on the original Gossip Girl, is successfully shamed into taking a gig writing for the reboot by his friend, Marcus, who always picks up the check when they get lunch together. Gordon reflects that the rest of his family has an “adeptness at being normal” that seems “evenly distributed and natural.” This is, if not purely a function of class, interrelated: “Everyone made more money than him, of course. They always had.” He acquiesces, helping to develop a Gossip Girl reboot for our apocalyptic times: Nate, Dan, and the gang are fighting for resources while the Gossip Girl blog provides tips for where to find clean water.

Gordon is neither normal nor cool. “People don’t take me seriously,” he complains to Marcus. “Being a writer is glam. Writing is uncool.” In working on Gossip Girl 3, though, he develops a close friendship with Nia, a trans girl ten years his junior who is definitionally cool. She also writes for the show, but Nia’s true job is, “to be cool professionally, to generate a persona that her fans, collectors, readers, and Onlyfans subscribers, could para-socially attach to and consume, cannibalistically.” She stands in contrast, not only to Gordon, but to the rich twenty-something children on Gossip Girl. She’s sweet, down to earth. Despite being a decade younger, she and Gordon are at similar stages of transition. “I tried not to be bitter about the life she’d get to have, the one that had been impossible for me,” Gordon thinks. “I tried to be happy that, whatever real life was, someone was living it.”

What becomes clear over the course of Gossip Girl Fan Novella is that no one has a very good grasp on what constitutes “normalcy” or “real life.” Or maybe that’s not fair; maybe the real point is that everyone is constructing their ideas of normalcy out of the pop culture visions they absorb, the “substratum of the hive mind’s dream,” as Nate calls TV. Normalcy is necessarily constructed in opposition to the unglamorous, the poor. On the 2002 film Minority Report, Markbreiter writes that Tom Cruise’s talent is, “looking so normal that he seems fake. He exposes the plasticky manufactured sheen of norms, not by cleaving from them, but by sticking to the rules with a serial killer’s rigor. The norm is revealed to be what it is: a fake, a statistical average, disaggregating into its disparate parts.”

It’s this fake normalcy, then, that is Nate’s, is Dan’s, is even—to a lesser extent—Nia’s, at least from Gordon’s perspective. It’s Nate who becomes the most deeply wrapped in, and warped by, it. It’s revealed eventually that it’s the bootleg puberty blockers his parents managed to afford—through wealth and influence—that have transformed him into his father. (This information is revealed by the ghost of Lauren Berlant, who talks to him through the TV; this seems, if not clearly thematically relevant, at the very least worth mentioning.) It’s not so much his desire to be Normal, as the way that wealth gives one command of the world, that embroils him in this Oedipal, Teen Wolf-y transformation.

In the book’s earliest essay section, Markbreiter analyzes the career of Cory Kennedy, the “first Internet It Girl.” Her period of It Girl-dom falls between the introduction of US Weekly’s “Stars: They’re Just Like Us” column (which suggests that you can be immensely wealthy but just like everyone else because you pump gas) and the early-10s rise of influencers. “You could argue that Cory wasn’t selling anything, at least not at first,” Markbreiter writes, “and that this was her magic . . . she was just being herself and getting paid for it. As everyone should be.” This is juxtaposed against later sections, such as “Fans,” which details the work of Steve Vander Ark, the creator of the Harry Potter Lexicon—a fan resource so thorough that J.K. Rowling herself is quoted as using it to refresh herself on details of her own universe. When the Harry Potter series ends, Vander Ark reportedly hates the series’ epilogue so much that he suggests fans “throw it away; it [isn’t] real.” “We’re taking over,” he says, and is caught short when he tries to publish the Lexicon. Sued by Rowling, the fandom turns on him, its “parallel lines . . . collapsing under fandom’s ultimately hierarchical structure.”

Again, a question of money: who is or isn’t selling what, who is allowed to sell it, to whom does any of it belong? No matter how much Vander Ark wants to reject the series’ ending, or to economically benefit from his labor, J.K. Rowling is a billionaire protective of her intellectual property, with legions of fans eager to close ranks around her. (After all, this, too, is a form of fan participation.) Rowling holds the authority of sole authorship, and copyright; there is no theme park in Florida based on Harry Potter fanfic. “However seriously fan fiction authors take their own work,” Markbreiter writes, “their writing is still considered minor by the broader reading public, not just because it pulls from existing intellectual property, but precisely because it is built communally.” It is made as a form of community participation, not monetary profit. (Nia, in Gordon’s sections, as an autistic teen, “made [her] first friends” on Gossip Girl forums.) To be clear, the book does not seem against Vander Ark for attempting to publish the Lexicon; rather, it’s remarkable how easily fan and creator push and pull against each other in Vander Ark’s saga. The mutual admiration and trust and benefit betrayed; the fan rejection of the canon work, the creator’s rejection of the fan’s labor the moment it stands to financially benefit him.

Things do happen in this book—many of them fun or funny (whomst among us, who have watched the original show, doesn’t want to see Chuck Bass listening to Sufjan Stevens while getting his prostate blasted with a water jet?). Gossip Girl 3 is a success and renewed for a second season; Gordon gets a bonus and attains some level of financial stability. (Though, at the same time, Nia becomes the star of her own show, far outstripping the level of success or cool that Gordon can achieve.) In the fanfic, the world is ending, and Chuck Bass’s no-longer-dead father is going to take Chuck and his girlfriend to Mars. Nate has long, stoned conversations with the ghost of Lauren Berlant, and eventually runs into them in a coffee shop (after all, they died only last year, long past the ending of the original show). This is all enjoyable, but it is Nate and Berlant’s conversations, the joy with which he greets them in the café on finding them alive, that stand out among the book’s plottier elements. There is a clear, deep love of Berlant—as a theorist and a person—on display, which is genuinely moving.

Gossip Girl Fan Novella is many things but, as is probably clear by now, straightforward is not one of them. Though there are complications in Nate’s desire to be Normal, there’s no finger-wagging about that desire; it’s not as though Nate is somehow in the wrong for transitioning when most people couldn’t. Autism comes up multiple times, most notably in a short fanfic about pop artists Dua Lipa and Charli XCX. Dua Lipa, “nothing if not a hard worker, decided to obsessively learn every social cue ever.” (Gordon is envious of Nia’s coolness but she insists she “just figured out how to be hot” as well as being a nerd. It is a series of steps to learn, codes to enact.) Normalcy, like pretty much everything else, is socially constructed; it pays socially to heed it. Analyzing its causes won’t change that.

This deconstructive tendency, as in Nate’s desperate pursuit for normalcy taking him further from the normal, recurs throughout Gossip Girl Fan Novella. “Every cliché is fake and true,” Nate says near the book’s end. “Love and hate are the same,” says Penn Badgley in You, “just a different way of knowing someone.” As Dan’s sister Jenny, actress Taylor Momsen was, “trying to access the real and she was running from it.” Trans theorist Colby Gordon is quoted as tweeting that dysphoria is a combo of dissociation and hyper vigilance, “inhabiting a state of not-knowing, a preventative strategy of cultivating a fog that occludes the obvious.” Jules Gill-Peterson describes giving up autonomy, “in the hope that power will govern us from the inside out and relieve us of the burden of being ourselves.” Early on, Markbreiter quotes Berlant’s definition of “cruel optimism” as that which “exists when something you desire is actually an obstacle to your flourishing.” While Nate and Berlant watch Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind in Nate’s hotel room, the narrator suggests that the problem is, “wanting at all. Wanting to want. But not being able to. Every fresh soda you open is somehow already flat.” It is want, desire, that undergird all of these dualities. A love for someone that sours; the yearning to transition cut with the awareness that you cannot change the size of your hands.

And it’s following Gossip Girl Fan Novella’s themes of desire that we return to love. Love does not counter the book’s conception of money/labor. Love isn’t a force stronger than wealth; it isn’t going to buy you hormones in the 90s, or save you from the apocalypse, or make you Normal. It isn’t going to save you when the most famous living writer sues you. But it is an act of love when Steve Vander Ark makes the Harry Potter Lexicon—even if it eventually sours. It is a kind of love that draws Nia to the Gossip Girl forums, or draws Gordon into his own fanfic about the podcast Nymphowars. These acts that are both individuating and communal, the pursuit of personhood and the disappearance into something larger than oneself. It isn’t fundamentally utopian; fandom, as Vander Ark’s story shows, is not necessarily more democratizing than any other contemporary community. That desire can always turn; “to have,” as Nate’s child psychiatrist tells him, “is only possible via the potential for loss.” But while it lasts it can be, as any love can, remarkable.

Katherine Packert Burke lives in Austin, TX. You can find more of her work at katherinepackertburke.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.