I first read Harald Voetmann’s novel Awake over a year ago. It almost feels shameful to mention—like I’m letting slip a dirty secret—but, initially, I read the book in fits and starts. It arrived at the end of a strict, four-month lockdown; I was bleary-eyed, fatigued, my brain scrambled, and slowly reacquainting myself with outside. It took me time to adjust to the real world and, by extension, to the machinations of the world Voetmann had created in Awake—I came and went from the text before eventually finding my groove and reading through to the end.

The troubles of the pandemic ebbed and flowed, then seemed to fade, replaced by other worries—such is life. But Awake stayed with me, following me into the new year. I thought of it often, of its formal unorthodoxy as well as Voetmann’s version of Pliny the Elder, an odd and belligerent figure. Unable to shake it, I finally returned to the book again, read it through quickly, and, for reasons I can’t quite explain, felt compelled to hunt down its author.

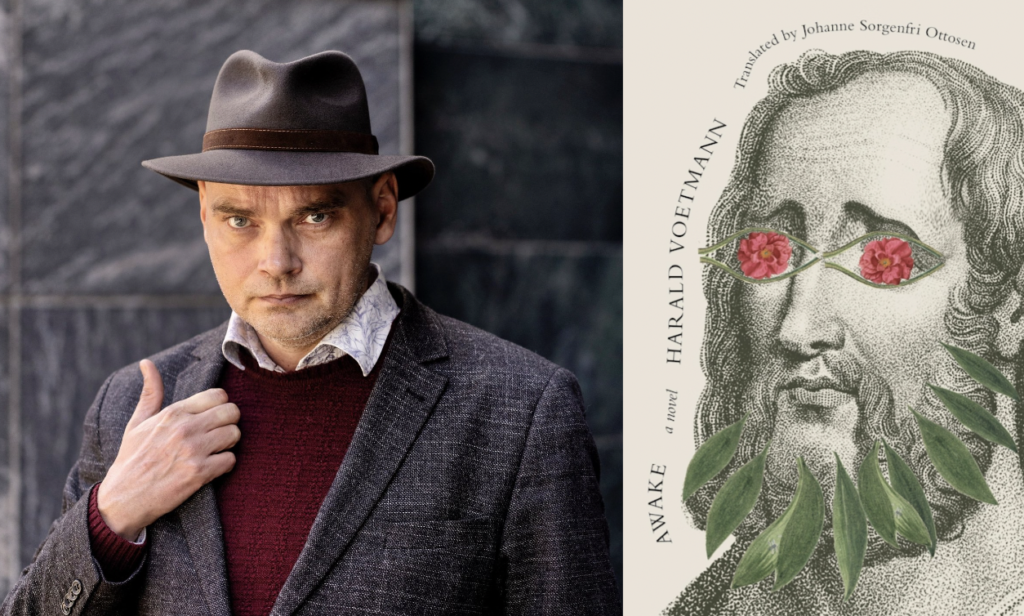

The following is a conversation conducted with Danish writer Harald Voetmann about Awake and its translation into English by Johanne Sorgenfri Ottosen.

Tristan Foster: The Pliny the Elder of Awake is a sort of everyman—remarkable in his attempt to catalogue the knowledge of man, yes, but as aggressively obsessed as the next person with the base elements of existence: sweat, piss, shit, blood, mud, sex, and death. He’s also temperamental and impatient, fearful of the natural world yet eager to catalogue its every atom. This is in contrast to the figure of history, where the centuries typically work to strip away any sort of humanity someone might have. How did this incarnation of Pliny the Elder come to be? Is this how you envisage a Pliny the Elder occupying the Earth at some point or a total figment of imagination?

Harald Voetmann: It is a gift for a writer to have a source like the Naturalis Historia. Pliny strives to catalogue everything in the natural world here. So there is a whole world written down, with its own weird set of natural laws—that goats breathe through their ears, for example. My intention was to write a book set in the world that he described. So this is not realism, but it adheres to his perception of reality and does not try to explain his beliefs when they differ from ours. I believe that there is a lot of Pliny the Elder as a human being—a lot of his personality—contained in his work. For one thing, he seems to have felt that he succeeded in his endeavor. Many later writers have dreamed of the work that is all-encompassing, but they have also been aware of the impossibility of it. The French Encyclopédistes, for example, they might have had some of Pliny’s pomposity, but they also knew that they were only scratching the surface. But Pliny’s prose is full of personality. Like Schopenhauer’s, it is pessimistic and melancholy, brooding over the suffering of all living beings, but also lively and imaginative and sometimes very funny. I was interested in his sometimes compassionate pessimism, which for me seems to be miles away from most of the Roman writers of his time. But I was also struck by how much he hates Nature. Nature as a goddess causing endless suffering on Earth for the sake of her own entertainment. His work was also an attempt to overcome Nature by gaining and collecting complete knowledge of her, and in the final sentence, proud and desperate, he tells Nature that now she must respect him. It interested me that there was such an outspoken hatred against Nature to be found near the root of the Western scientific tradition.

In your interview with Denise Rose Hansen, you mention that the book takes the form of an antique drama. This is instructive, though for me, the book reads as a collection of dialogues—Pliny The Elder with his text, Pliny the Younger with Pliny the Elder’s legacy, Pliny The Elder’s slave and scribe Diocles with his master via the act of writing. To my mind, the success of the execution of Awake is a matter of voice. What was the thinking behind the formal choices you made with the novel?

The literary voices of Pliny the Elder and Pliny the Younger are so different. Compared to his uncle with all these obsessions and delusions, but also real interest in the world, deep pessimism but seemingly real compassion, Pliny the Younger appears to me more like a bland, elegant courtier, absorbed in the fashions and machinations of his bubble-world. That might be harsh, as is my portrayal of him in the book. But one of them is obsessed, the other in control, and I will always be more interested in the obsessed one. Letting the voices stand next to each other and sometimes engage directly with each other highlights them both. I did use the antique drama as a template, mostly in the way it shifts between episodes with some action and more reflective passages. And the Hybris/Nemesis-theme is also there of course: What happens to the man that demands respect from the goddess Nature? An erupting volcano is the only appropriate response. But no, it is not drama in a straightforward sense and it would never work on a stage.

Before its publication in Johanne Sorgenfri Ottosen’s English translation, Awake originally appeared in Danish in 2010. I’m curious to know how a work changes for you over time, especially in light of the process of translation. Does it remain fixed in your mind or does it evolve? What is gained and what is lost?

It came out in Danish twelve years ago, and I have written a lot since then. This was my fourth book, but, as I see it now, it was also the real beginning. The previous books were only sketches. I don’t usually pick up my books again once they are finished—except for when I have to read excerpts on stage—so when I read Johanne’s translation it was the first time in more than a decade that I actually read it from beginning to end, and now in a different language. And I was impressed by the way she had made it come alive. I could remember most of it, my ideas, and where I was when I wrote it. But still it was darker and much more brutal than I remembered. I would have written it differently now, but that would not necessarily have made it better. It was written by a young man. It seems to be screaming from start to finish and I stopped doing that long ago and probably could not pull it off if I wanted to. But I do remember why I felt the urge back then.

“The urge to name and classify the world’s miseries. Why else should we have been placed in their midst with this talent, this gift?” Pliny the Elder, fictional character but also historical figure, is painfully aware of his mortality. He is aware of the passage of time and of the limitations of human existence—indeed, he refuses to sleep because there is too much to see, read and record. Is Pliny the Elder one in a long line of people—Aristotle, Cato, Diderot, today’s Wikipedians—who experienced a burning desire to record human knowledge or is there something else at play in his impulse?

One difference is that he seems to have felt that he succeeded. Even though he does admit faults and doubts in a few places: “I have no doubt that much has been omitted,” and: “A few things still need to be said about the world”. There are also many hints that he is motivated by this desire to conquer Nature by being the first to know all about her. Again, Nature seen as a goddess. He tries to muster some heroic masculinity against what he perceives as the feminine cruelty of the natural world. And this view of the goddess Nature is completely in line with the way he writes about women in general, with equal parts fear and contempt.

Speaking of impulses, I’m curious about your impulse to write. Why writing, and why writing in a world which seems to be turning more and more to visual media?

I am not very good at cooperating. I did write a play recently; it was performed in Copenhagen this summer, and I watched some of the rehearsals and tried not to interfere too much. Although the feeling of community was alluring, I am too used to playing God. There is an idea that visual media have completely revolutionized the art of storytelling, but I am not so sure. Few would feel the need to write page after page describing the dusty furniture in a boarding-house in Paris like Balzac did. I think that has to do with visual media, and also just the amount of noise, information, light, and distraction everywhere. But right now I am trying to translate Catullus into Danish. It is frustrating and lonely work, but it also gives me the opportunity to really dive into his poems. And looking at Catullus’s poems 63, 64, or 68 is breathtaking, these complex landscapes, carefully constructed two millennia ago. That is some of the most technically sophisticated and complex storytelling I have ever experienced, and my so-called translation will of course fall short. And, in my opinion, so does visual media in comparison.

It is possible that your influences are clearer for those who can access your body of work in Danish, but given that, so far, we only have access to one of your books in English, I’d like to know: Who do you consider your influences?

There are so many, and of course many contemporary Danish and Scandinavian authors. A couple of years ago I wrote a short book—about the same length as Awake—that was a Covid-era pastiche of Hans Christian Andersen. I think most Danish writers would be able to make a decent impression of him on the spot. They do not necessarily read his works, but his voice is instantly recognizable. But when I was younger, it was only the heavy stuff. Djuna Barnes and Samuel Beckett both made a deep impression. García Lorca’s Poet in New York as well, although it is very different. The past twenty years I have read a lot of pre-modern literature and much of it in Latin. Also to keep practicing the language and learning more. And I can sometimes find raw material and building blocks there, but very rarely direct artistic inspiration. It is no fun talking to the dead.

Something I’m forever intrigued by is the relationship writing and literature has with fun. Part of that is the fact that the act of writing is often framed as being very difficult, and part of it is due to the seriousness with which literature is discussed, as if it is this sacred and weighty thing—these discussions can border on the ecclesiastical, and rarely does a sense of fun or play get a mention. Yet it almost goes without saying that literature can be a lot of fun, and be very playful; indeed, there are entire literary movements that have play at their heart. And so one of the things I’m deeply attracted to in your writing is its playfulness. Is writing fun for you?

The Hans Christian Andersen book was a lot of fun to write. But that was also a conscious decision: This time I need to have a blast. The book I had written before that had to do my father’s death and it was a horrible process, emotionally exhausting. And I felt like giving up writing completely after that. I didn’t feel it was worth the effort. But I decided that the next thing I wrote had to be fun for me, no matter what the reader might think. It was written in about three weeks and is overtly sentimental, sticky and sweet and with Hollywood strings. Which was probably a bigger shock for some of my readers than the brutality of Awake. And it did give me the energy I needed to continue, knowing that I can always throw another party when necessary.

I first read Awake almost back to back with When We Cease to Understand the World by Benjamín Labatut. This was purely incidental, and while the intent of each book is totally different, they entered into neat dialogue with one another in that both books endeavor to enter the imagined world of significant moments in history, allowing the reader to share the personal space of historical figures. Awake is the first in a loose trilogy of novels retelling the lives of important historical figures; next is Sublunar, due out in English translation in 2023, followed by Visions & Temptations—both of these novels are set in other moments in history. What is the attraction to exploring the past in this way?

So many stories try to deal with the present by looking at the near or distant past. We always hear that exploring the past widens our understanding of what it means to be human. Or something like that. History is fascinating and we do need it to understand ourselves, but looking back is inevitably also looking into a pit of pointless suffering. And literature has a different set of tools for dealing with that than history books. Not better, but different. It can offer the illusion of time travel and bring the senses to life so we feel we can catch glimpses of a different world from a safe distance. But my interest is not so much with the genre. I am not sure I will ever write another historical novel. These just felt like the right thing to write at the time. With Awake I was interested in letting the proto-scientist Pliny speak of his hatred towards nature now, in a time of ecological disaster. Let him applaud us. With Sublunar I was interested in Tycho Brahe’s unwitting and unintentional destruction of the concept of eternity, and the way that exact modern science (chemistry, astronomy) germinated in a swamp of messed up hermetic mysticism. With Visions and Temptations I tried to write about Medieval Christianity in a world that is still so affected by all sorts of religious extremism. I think if you look at the three books together they might also be about the different systems of thought we construct: philosophical, religious, scientific, and our lives within these systems. We tend to build them and they always tend to crush the humanity out of us.

Tristan Foster is a writer from Sydney, Australia. He is the author of Letter to the Author of the Letter to the Father and 926 Years, co-authored with Kyle Coma-Thompson. Midnight Grotesques, with Michelle Lynn Dyrness, is forthcoming from Sublunary Editions in 2023.

This post may contain affiliate links.