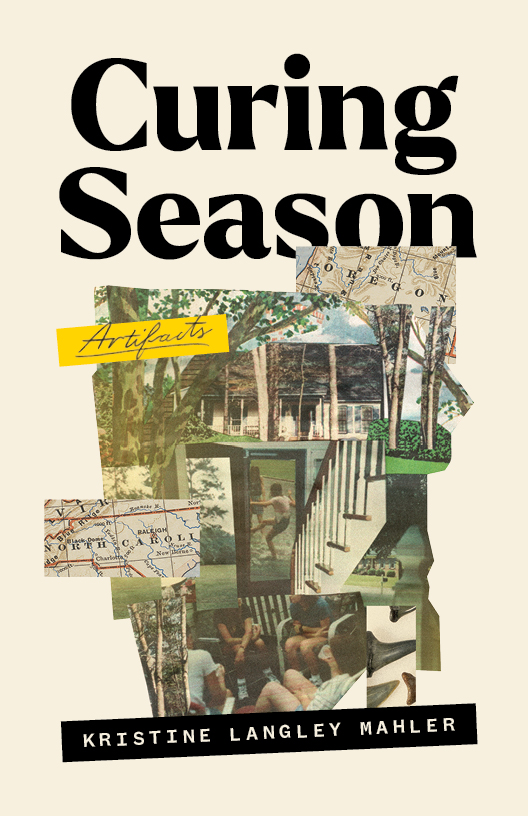

[West Virginia University Press; 2022]

In the third grade of a from-the-cradle Catholic school, we started the year with two new students. This was rare; the majority of us had been stumbling forward as one unit since preschool. One of the kids became my best friend, and still is. The other left in—fifth grade? Seventh? A week after their appearance?

It’s hard to say. I have flickering memories of this person: crying on the playground, a birthday party in a cool basement, a name in the flimsy school directory. There are people who come and go in your life, scattered as barely more than snapshots. If you recall them at all, it isn’t as another human being, but as someone existing only to be recollected when exchanging stories with the friend who stayed.

In Curing Season, Kristine Langley Mahler’s jarring, unusual, and deeply moving collection of artifacts and ruminations, that recollection comes to life. Mahler is the person who briefly flicked through the life of a strange town and classmates, before leaving again. She has been deeply impacted by those short years, even as she questions her impact. What did her life mean there? What did it mean to be in this southern town, with its own deep history, and amidst classmates whose families are intertwined? What does it mean to pass through the lives of others? How do these events shape us?

And throughout, Mahler hints at one persistent thrumming question: What happens to the person who can’t forget what no one else remembers?

Mahler, a memoirist who lives outside of Omaha, grew up in the tall trees of Oregon, living a rustic and idyllic academic childhood (at least in her recall). She was ripped out of that life when her parents moved her across the country, to Greenville, North Carolina, a suburban town that at the time of moving still seemed on the edge of the wild, teetering on the edge of homogenized banality.

The move came at a time in her life when she herself was teetering on the edge—not a small child, not a teenager. While the family only spent a short time in Greenville, it was a crucial point. As she puts it, quickly and brutally, “Nowhere hurts like the place you learned to be hurt.”

I appreciated that on the surface of her story at least, there is nothing so dramatic as to be hurtful. The book opens with an extremely useful bit of formal inventiveness: a series of quick paragraphs about different houses. Her friends, friends of friends, with a memory in each one. For instance, Katy’s house:

Her mom has macaroni and cheese waiting when Katy gets home from school and Katy eats dinner at 4 p.m., sitting at the kitchen round table alone, and I’ve never heard of eating so early and I’ve also never eaten dinner without my parents and siblings. Afterwards, I introduce Dirty Barbies to Katy even though we are ten and I assume she’s played this game before. She has, and she knows new narratives.

Some houses—some people, some moments—are more important, more foundational to her life experience. But everything has an impact, especially at such a young age. Occasionally, the short little bursts intersect, or a moment carries over, but not always. They are stand-alone except for how they have helped shape her childhood and her adulthood.

The formal inventiveness in this quick, dreamlike tour of houses and memories is neither a gimmick nor mere exposition; it’s a very effective reflection of the way memory works. Except for a cursed few, no one remembers everything. Our memory is stitched together by flickering vignettes, moments half-recalled, sense memories of mac and cheese or a house stinking like smoke or finding a mean note from someone who was your best friend.

Mahler’s experiment with form, with the nature of memory, continues throughout the book: She grafts real histories to farming techniques, and she has a section of photos that illustrate the town, juxtaposed with her life. In many parts, it feels like opening a strange chest of drawers, black-and-white clippings fluttering to the ground, scooped up and examined briefly.

Throughout this first section and others, the deliberately childlike memories shift a bit, opening up some absolutely bravura writing. A short chapter, titled “She’ll Only Come Out At Night,” begins:

Our guts churned as Shelly dared us into a game of “Who’s Got the Nerve to Hit Me” on those viscous, smothered summer nights at the park behind our neighborhood, our parents encased in air-conditioned houses . . . but we melted out our front doors and swiped our kickstands with our insteps and the yellow streetlights streamed off our exposed shoulder blades as we cut swathes through the swelter, merging, drawn together to the park.

This is more than just great writing, though it is also very much that. It’s evocative of those youthful summer nights where freedom seemed possible and terrifying. It captures a perfect moment where swiping kickstands feels less like real movement and more a step toward actually growing up. It’s a thrilling and scary moonlit moment, sweat and nervous laughter and show-offishness covering nerves. The world glimmers with potential. But that comes with the terrible fact of change.

Her best friend is Annie, and the fallout from their falling out is the central thrust of Mahler’s book. A long middle section, addressed to Annie while using Margaret Atwood as a guide, explores what the falling out meant, how it hurt Mahler, how it was, indeed, the locus of her life’s hurt. Even in this, Mahler demonstrates how, while memory shapes our emotions, emotions can easily distort memory.

At which I dare not look because it is easier to blur the lines of the narrative into a convenient truth: I do not stare directly at our friendship but amplify the glare of my isolation and your part in it. I start to lose touch with the real events. The constructions take over. . . . It was easier to ignore the upheaval and inconsistency that must have rattled you and focus, instead, on the role I needed you to fill as the cause of my pain, that cherished, tender bruise I’d slam against a corner when it started to yellow. You provided an explanation for my adolescent distrust, my well-building: you did this to me.

The details of Annie’s life after she, too, moved away from Pitt County deny the chance at solace or healing. The entire section is an emotionally confused jumble of past and present, a rising aria of grief that settles into the bones of the reader. You feel the loss, and you feel the knowledge of that loss. Loss creates a memory that has nowhere to go.

Being lost in time is, if not a recurring theme in Curing Season, a constant idea. Greenville, in Pitt County is, even in a growing and changing North Carolina, a southern town with southern problems. Race plays a large role in the life of the town, and a small but distinct role in Mahler’s life.

It is somewhat surprising, after such intense personal stories, to look at these issues at a high adult level, but her memories of how she interacted with race and racially motivated events are some of the book’s most vivid and visceral moments. A story of Black teenagers causing normal teenage trouble in the neighborhood from a childhood perspective, with both fear and a nauseating guilt about the fear, navigates the burdens our nation’s sick history places on minoritized people.

What is most interesting is how Curing Season slowly evolves into being more and more about these burdens and histories, about how they are still present in the rich, tobacco-stained soil. It is in these later sections that Mahler plays faster and looser with form, to great impact.

Mahler looks at the family stories collected as hand-me-downs in The History of Pitt County, grafting short stories and old mythologies, all of which make clear that there were rulers and the ruled, with a guidebook about agriculture, and, eventually her own ferocious thoughts.

In talking about how she “wanted to belong to that county harder than I’ve ever wanted anything before,” Mahler dives deep into questions of ownership and belonging. Lineage, she says, ruled everything. Nothing new could grow; if one didn’t have roots—if your family didn’t have graves in the town, white graves—the town would eat you up. As she says, talking about fertilizer: “the soil ate it up, the native plants ate it up, consuming anything new and leaving nothing behind once the harvest is over.”

The effect is stunning, as it truly ties together the way that the history of a town is grown: It is molded and shaped, it is created like a new plant. The story of a person, and a town, is as much about what we pretend to remember and decide to forget.

In the end, that is the thread that runs through the book. We’re a collection of our memories: where we’ve been, and the people we’ve interacted with. It could be a town going through changes, mirroring our own—one of the most evocative images is an old graveyard around which a mall, now closed and useless, has been built, a perfect encapsulation of the throat-clearing respect we pay to history as we grind it to dust.

Mahler remembers things that no one else does. The town forgets her, just as it works to forget the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow that still shapes the lives of its people. It is, like so many other places, a town of smiling amnesia for those lucky enough to forget.

Some people can’t. Some people have to remember what no one else does. They don’t have a choice. Mahler holds a mirror to memory, that inconstant force, that unsteady driver of everyday. The book is long on impeccable writing and devoid of easy answers. We might be reading a story of a short handful of years in a life, but we’re experiencing memory itself.

Brian O’Neill is a freelance writer who mostly enjoys writing about books—small press fiction, memoirs, the Midwest, and international politics. Also, baseball. He tweets about all of that @oneillofchicago.

This post may contain affiliate links.