Few people in the literary community create as many fun and meaningful opportunities for writers as Ander Monson. From editing the magazines DIAGRAM and Essay Daily, to running New Michigan Press, to hosting an annual March Madness-inspired writing tournament dedicated to essays about music, Monson creates unique spaces for many writers of all stripes to share their work.

Monson’s own work spans three genres: fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. He is the author of eight books, including The Gnome Stories and Other Electricities; poetry collections, Vacationland and The Available World; as well as four works of nonfiction, Neck Deep and Other Predicaments, Vanishing Point, Letter to a Future Lover, and I Will Take the Answer. His awards and recognitions are too many to list but include various prizes and fellowships, from the Annie Dillard Award for Nonfiction to a Guggenheim Fellowship. He is a professor at the University of Arizona.

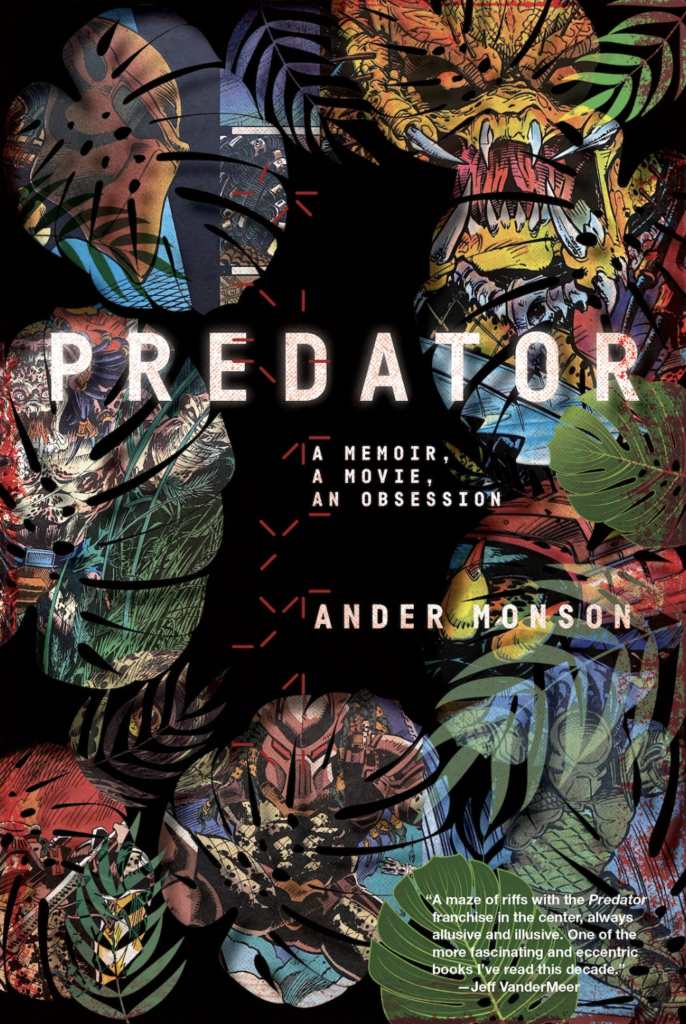

In his new book of nonfiction, Predator: A Movie, A Memoir, An Obsession (Graywolf Press, 2022), Monson explores the culture and fandom surrounding Predator, the 1987 action film starring eventual governors Arnold Schwarzenegger and Jesse “The Body” Ventura. He observes that:

The movie hasn’t left us the way you’d think, like others of its ilk (Commando, for instance, or Raw Deal). Predator is a movie about both the future and the past. It’s a sci-fi movie wrapped in a horror movie wrapped in a war movie wrapped in a space movie. It’s satire wrapped in gun pornography. It’s tenderness wrapped in beefy macho posturing and explosive ballets.

Monson has now seen Predator over 150 times and counting.

To be honest, I’ve always dug Predator well enough, but I’d somewhat forgotten about it since my adolescence. As a life-long sci-fi enthusiast, Predator never stuck with me like Ridley Scott’s 1979 film, Alien. You might think Monson’s memoir has reordered that thinking, but it has not, because promoting Predator isn’t really his intended effect (though he does love talking about Predator and sharing the fandom).

Instead, Predator: A Movie, A Memoir, An Obsession shows what films, books, games, artworks, or sports can reveal through analyzing a thing and the culture around it. Even campy “big dumb movies,” as Monson calls them, offer entry points into deeper understandings of the self and others. When Monson explores why he’s obsessed with Predator, it’s an invitation to ask yourself why you’re obsessed with Slayer, or My Little Pony, or Keith Herring, or The Raiders. What does that obsession say about you? About others? What can an action film teach us about masculinity, violence, eroticism, fear, or love? When the book examines what Monson’s love for Predator reflects, or fails to reflect, about his values now and throughout his nearly life-long relationship to the movie, we can ask the same questions about our obsessions.

After rewatching Predator (twice), reading Paul Monette’s novelization of the film and, unfortunately, watching Alien vs Predator, I came up with some questions that Monson was kind enough to answer. His responses demonstrate the same iconoclastic insight as his memoir.

Eric Aldrich: Part way through the book, you write, “I believe that if you look hard and long enough at what you loved best at fourteen and how you lived then and what you saw in the world, it will reveal both the world and you. Or maybe you’ll exhaust it, or it’ll exhaust you.”

Predator is heavy. Campy as the violence and death may be, skinned bodies and soldiers burning alive make for gruesome content. I mean, I enjoyed listening to the band Napalm Death when I was fourteen and I still do, but I can only listen to so much Napalm Death. It crowds out room for more rejuvenating and hopeful thoughts. I guess it exhausts me. Now that you’ve written the book, is your relationship with Predator waning? Deepening? Are you exhausted by the film, or will you hit two hundred viewings in the future?

Ander Monson: I never could get into Napalm Death, however much their artwork and the shock and awe of the band name spoke to me; I found them then—and find them now—exhausting, but when I listen to, say, The Real Thing or, even better, Angel Dust by Faith No More or really almost any AC/DC, I find it invigorating. I returned to “Surprise, You’re Dead” on The Real Thing a lot over the last couple years. It’s the perfect song for playing, say, N64 Goldeneye in Death Match mode, just fucking up your friends. It’s among the more adolescent songs I can imagine, listening to it now, but it’s so satisfyingly adolescent. It’s not exhausting: It kinda turns me on. I’m embarrassed that it does, but it does. I thought that was a lyric from the song, in fact, and when I looked it up to confirm it, I was surprised to learn that it’s not “I’ve drank and swallowed, and it turns me on” but “I’ve drank and swallowed, but it’s just begun.” I listened to it a couple more times to be sure, and I guess I can hear that, but I still don’t believe that’s the actual lyric. I think what you probably need to do, though, is to go deeper into it or cultivate a more expansive view of it if you’re going to let it reveal you. Like it’s not just the thing itself but all the stuff around the thing, adjacent to it. The thing itself may be boring, but if you zoom in or zoom out you’ll start to see adjacencies and all these other compelling resonances. I love Predator but I’m much more interested by the culture that made Predator and the culture that continues to make and continues to watch and rewatch Predator. If I was just looking at the movie I wouldn’t see that.

I mean, there were certainly times when I got tired of Predator. There are still times when I watch it where I realize I’m bored by one part, like the rote action sequence of the guerrilla camp or the kinda dumb and anticlimactic Dutch vs Predator Rocky fight at the end, but when I go deeper into the world of Predator, say its fandom or the novelization, my excitement comes back up. So part of the job of looking is, especially when you find yourself exhausted by the thing, to move closer to it, move further back from it, and look at the stuff around it. I mean I understand Predator in a different way when I read the novelization or when I read Archie vs Predator or when I talk to guys who DIY their own suits. When I see how others see Predator I learn to see it in a more faceted and expansive way.

I would be surprised if I don’t get to two hundred in the next year or two, especially with the thrill of watching it on the big screen again, which I’ve only done three times now, and which I’ll be doing at a lot of the book tour events. It’s thrilling in a different way watching Predator in a shared space with other people, because the experience changes with the people. Am I done writing about Predator is the harder question, and I don’t yet know the answer to that. For me it keeps unlocking other doors, and as long as those doors are interesting ones I’ll probably keep writing at it.

One thing watching Predator seems to have revealed about the world and about you is the conflicted relationship to masculinity many men share, including discomfort reflecting on how we performed masculinity in our youth. You write, “As men, we’re almost watching ourselves watching ourselves when we watch action movies: we know their grammar, and know how we respond, and how we’re meant to get pumped up about getting pumped up.” Violence, bravado, shirtless glistening, explosions, beautiful women in handcuffs, these things get men “pumped up.” Masculinity is campy, like the film Predator, but it is also irrational, deadly, and predatory.

The memoir exposes a contrast between the events on screen and the events in your life with your daughter. You describe doing a Turkey Trot 5K in a tiger suit while pushing Athena (also in a tiger suit) in a stroller through a water obstacle. You write about protecting her from seeing the violence of first-person shooter video games. You mention Christina Taylor, the nine-year-old girl murdered by Jared Loughner in Tucson, several times and it’s clear her death is empathetically imprinted on you. The memoir explores the struggle between the violent, pumped-up machismo represented by Predator and the peaceful, equitable, and safe world we wish for today’s children and future generations. But, as you point out by citing January 6th rioters and mass shooters, we still live in a world more Predator than utopia.

I have a little trouble pinning down your thoughts on violent media in the memoir. You play the games you acknowledge are problematic enough to protect your daughter from and see the Predator commandos in January 6th rioters. Is violent masculinity inescapable in the art/life dialectic? Can self-reflection and cultural analysis of the type you present in Predator influence behavior and values, or are the people most in need of self-reflection beyond reading and critically engaging with films in the ways you have?

What I’m trying to do in the book is make and try to model a case for a larger masculinity. The kind that’s more permeable, thoughtful, and capable of self-reflection, though no less thrilling; the kind that’s more able to see itself and acknowledge its own contradictions, to enjoy Predator AND to be able to look at itself enjoying Predator; the kind not freaked out about its own vulnerability and forays into femininity. I want a capacious masculinity, a masculinity that’s able to look and laugh at itself. I don’t want to eliminate Predator: I love Predator. I can’t not love Predator. But I do want to hopefully lead some people to look at Predator a little differently and understand it—not just Predator but the act of looking—as the tool it is, and I hope show them how to use that tool. There’s a moment in the newest iteration of the franchise, Prey, where our protagonist witnesses the Predator use one of its cool alien tools, and she figures out what it does and how it works, and—spoiler alert—deploys it later against the thing to help her finally kill it. I absolutely think that watching Predator is a tool we can use to better ourselves, to become at least fractionally bigger in our conception of masculinity and to understand its power and its contradictions and its flaws. And to expand that line of thinking to let us think more capaciously about humanity, too, because what we’re doing right now isn’t working that well, is it? As Gary Busey notes in a press interview for Predator 2, we seem to keep warming our planet; it’s getting pretty hot! And if these things only come in the hottest years, as Anna says in Predator, soon they’re going to be coming all the time. That is, as we all arm ourselves and heat our world, we’re bringing these creatures on ourselves. I’m not for getting rid of the tools we need to see ourselves; I’m for using them. So maybe try them out before we’re all superheated and hunted to extinction?

In the novelization of Predator, Paul Monette decouples the alien from its humanoid form for much of the book, instead depicting it as a disembodied shapeshifter haunting the jungle. In the movie, the Predator is humanoid, falling somewhere between Conehead and Wookie on the human similarity scale. You say, “He is us but he is alien.” Furthermore, sport hunting is a very human behavior with masculine motivations. As you put it, “What’s hunting us is us, Predator tells us. It’s a version of us—male, equipped, single-minded, armed, aggressive, showy, and powerful—but in all of these prized male qualities it’s more amped than us. It kicks our asses.”

This issue of the Predator’s body seems like a critical difference between Monette’s novelization and the Schwarzenegger film. How different can bipedal, bi-brachial creatures with bilaterally symmetrical faces on neck-mounted heads be, right? Is the Predator just a mirror to Schwarzenegger’s character, Dutch? How much does the alien’s infrared perspective we enjoy in the film take us out of our human point of view? And do you have a theory why Monette changed the alien’s corporeal nature?

Novelizations are typically written based on earlier versions of the script because the book has to be timed to come out with the movie’s release, so that’s the difference: The shape-shifting nature of the creature is from an early script; it isn’t (I don’t think) a Monette invention. But it is a radical difference. What I do think is his invention is the idea that the Predator gets obsessed with humans because we are the only creature it encounters on this planet where it cannot assume its form—because, in the novelization, only humans have souls. This raises more questions than it answers. The one thing that’s sure in both novelization and movie is that the creature is curious about us, which is why it watches our men and listens to their jokes and tries to figure out the way they interact. It does weaponize these things, but beyond that, its curiosity still hits me. It hit me when I was twelve, I think, though I wouldn’t have been able to articulate it then. But that idea stuck, that we could be it. And being it, getting to look at ourselves as it, through its eyes, is a sweet deal. This obviously resonated for a shitload of other people, because getting to be the Predator is the killer app of the movie and the franchise, and the centerpiece of the whole AVP fan universe is cosplay as the Predators. Getting to be the Predator is also the most fun thing about any of the video games in the series, though that doesn’t really come to fruition until the AVP crossover, because while the tagline for AVP was “whoever wins, we lose,” that isn’t quite true: The Predator may be alien, it’s at least understandable. The xenomorph (the alien from Alien for the uninitiated), however, is totally unknowable, and if it wins, everything’s over for humans. So the human and the Predator are much more closely aligned.

The first video game where you could play the Predator is Alien vs Predator: the Last of His Clan for Game Boy (1993), but the genre really hits its stride in 1994’s Alien vs Predator for Atari Jaguar, which offered one of the more memorable gaming experiences of my life, and let that idea grow in me: In it, you can play as the xenomorph or you can play as the colonial marines or you can play as the Predator. The thing obviously is a mirror for Dutch, as they get to trade their iconic lines at the movie’s end: What in the hell are you / what in the hell are you? But more than that, it’s also an invitation, maybe an easier one to take up for most of us. Though it’s alien, it’s not that alien.

You spent time in Paul Monette’s archives in Los Angeles researching the author’s journals during the time he novelized Predator. In the memoir, you describe his connection to the novel as somewhat perfunctory, hemmed in by contractual obligations to portray the script and overshadowed by the final days of Monette’s partner, Rog, who was succumbing to AIDS-related illness as Monette wrote the book.

How much are the novelization and the film blended in your mind? Do you have a distinct awareness of the differences separating them or do you graft relationships and character traits from the book into the film, or vice versa?

I can’t not think of both of them, but the central experience is the movie. The novelization functioned for me as a lens. It cued me to the queer reading of the film. It also gave me permission to understand and write into and about beauty as a subject in itself, which once you start paying attention to it, is everywhere in the film, but I never thought about the movie in this way until I read the book. That’s the permission the poet gives us. That’s the permission good poets give us in looking at everything, which is why poets should write all of the novelizations and a lot more of the movies.

Having said that, it’s also worth saying that the film is much deeper than the novelization in most of the ways that matter: The characters and their relationships are far better and more nuanced (the casual racism of the novelization and the lack of imagination it implies is pretty hard to ignore, reading it thirty-five years later). So the book remains ancillary to the film, an oddity for sure, and not just because its substantial differences from the film take it out of canon.

If he was alive, what do you think Paul Monette would think of your book?

A wild thought. I hope he’d respect the work, or if not the work, then at least the quest.

Can I pose a critique of the film and get your take on it? I get the Predator is an extraterrestrial and that is an asterisk beside this reading of the film.

Predator resembles fears spread about Indigenous people since European colonialism began—Indigenous hunters silently stalk and kill white soldiers in the forest and do so out of “savage” fear, for sport, cannibalism, or motivations beyond colonial understanding. The skull-collecting Predator embodies a “primal” fear, with “primal” taking on significant colonial overtones. It hunts European, white, and African-descended soldiers, the colonial demographics of the Colombian Exchange, as they interlope in a deep “New World” jungle. The people of color die and the European not only lives, but defeats the indigenous “alien,” and even rescues a damsel in the process. The film wraps colonialism in the post-Vietnam era and appeared at a time when jungle commandos ran actual missions in Central America, so the immediate historical content eclipses deeper history. But still, to what extent do you think Predator is a colonial “Heart of Darkness” story?

Yeah, that’s here, I think, but it’s also a story largely about betrayal by the American government. The team is sent here by the military under false pretenses and seems entirely aware of the fucked-up nature of American expeditionary wars. They’re maximally geared up in the American way, and all of that technology is totally useless, at least when confronted by a more badass thing than the badass things we’ve been following through the jungle and been rooting for. The more I watch Predator, the more I find plausible the reading that the predator is the protagonist. I just watched it for the first time with my nine-year-old daughter tonight, for instance (viewing number 154), and that was 100% her read. She was visibly disappointed when we get the requisite Hollywood ending, where Dutch survives. I think the invitation is very much there to root for the Predator as a kind of consequence for and corrective to the historically horrific behavior of humans—maybe not these individual humans—but what they represent, as you point out: the colonizing force, the civilizations that have been largely responsible for heating and arming and destabilizing and fucking the world to the point we’re at. Sure, Dutch survives, but barely. There’s no triumph in the end of the movie: I barely even see relief in that last shot. Dude looks broken. His whole team: wiped out. All his friends: gone. Whatever ethos he had about the kind of work he and his were doing: destroyed. Whatever sense he had of humans’ place in the world is just completely gone. McTiernan even notes this in his director’s commentary. He tells us that the movie ends on such a sad note he wanted to give everyone a curtain call in the credits where they were all smiling. All of them except for Schwarzenegger, at least.

Would it have been a better movie if it centered the Indigenous over the European? More admirable and interesting, especially by the standards of the time? Totally! The newest one in the franchise, Prey, does this very well, and as such changes the nature of the franchise. But no way do I think it would have been possible to make that movie in Hollywood in 1987, or even 2017 for that matter, and not just because of the lack of imagination of all involved, but because of the forces that made—and still make—movies. I do find that read of the film plausible, but I also find plenty of evidence that the movie is subtly interested in dismantling, undermining, and satirizing the structures and agendas that made the movie possible to make in the first place. This set of contradictions is partly why I find the movie so rich and rewarding to return to 154 times and counting. I mean, that and the men and the guns and the explosions.

You can read Eric Aldrich‘s recent work in Terrain.org, Euphony, Essay Daily, and Deep Wild. He lives in Tucson, Arizona; ericaldrich.net; @EricJAldrich on Twitter.

This post may contain affiliate links.