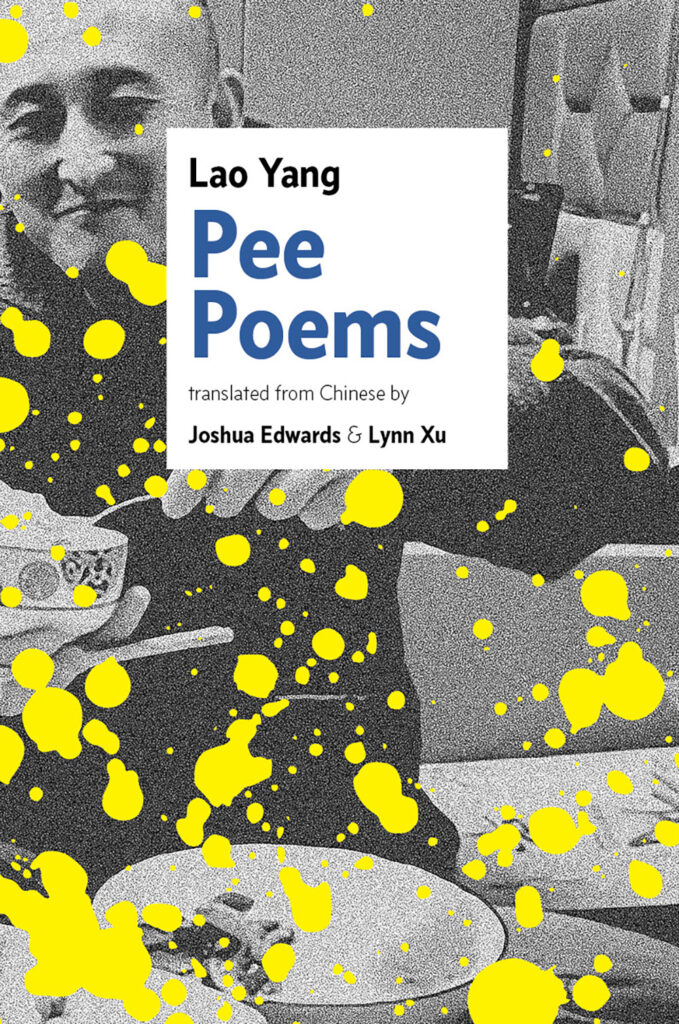

[Circumference Books; 2022]

Tr. from the Chinese by Joshua Edwards and Lynn Xu

In their translator’s note, poets Joshua Edwards and Lynn Xu include a statement by the poet and artist Lao Yang after Chinese authorities destroyed his Beijing-based art studio: “Until we have secured our rights, we cannot practice art, cannot live with art, cannot think artistically or observe this world with an artistic eye.” What, then, is poetry written after art itself no longer feels possible? Completed in the wake of this destruction, Pee Poems is Lao Yang’s answer in verse. It’s a formally bold work of irascible freedom and scathing political commentary, but also, at its core, a poignant lament for human transience.

Irascibility is key to Yang’s voice and manifests as hostility to the traditional lyric. Yang declares in the opening lines of the book, in a preamble: “Suffering from stomach cramps, kidney problems, and muddled thinking, I wrote some pee poems. / Don’t call me a poet, call me a piss person.” The centering of urine rejects poetry’s traditional subjects in favor of a more egalitarian common denominator. At the same time, because the act of urination is essentially solitary, Yang’s emphasis on “pee” and “piss” symbolizes a stubborn individuality.

This stress on the individual is formally mirrored in the “verses” that comprise the basic unit of Yang’s poetry. They are, in some ways, similar to the traditional stanza: Each is relatively short, consisting of one or more lines, and separated by white space. But Yang separates his verses with a star (“*”) in addition to white space, and never enjambs across verses. The effect is of isolation and independence; the verses feel almost as discrete as separate poems. This is underscored by the fact that Yang lists the number of verses on each section’s title page. For example, though the “Pissing Poems” section actually contains four separate poems, each with numerous verses and bearing its own title, Yang chooses to emphasize the granular verse-unit over the poem-unit by enumerating the number of verses in the section:

PART ONE:

PISSING POEMS

36 VERSES

Despite the formal independence of each verse-unit, they interact vividly with each other. Yang’s verses often undermine or comment on preceding verses, or, like a stone tossed in a pond, interrupt a poem with a line of seeming nonsense. The alertness of the verses to each other and their rapid fluctuations in tone and image create a sense of play and vitality. This is illustrated in an example from “UFO”:

I follow your tears all along,

Until I step into that rushing river

. . .

Finally adrift in the salty sea.

*

So many get squashed

In revolution’s revolving door

*

Stay stool stare star

*

You are talking to yourself

The first verse’s elegiac tone is immediately dispelled in the second verse (“squashed / In revolution’s revolving door”). However, the multiplicity of verse one’s “your tears” echoes in the “many” sacrificed for revolution in verse two. And then, as if reacting against the very notion of the poet’s capacity for articulating such immense historical and personal traumas, the third verse is a line of nonsense. (In Mandarin, the four words rhyme, which underscores their nonsensicalness.) Finally, the fourth verse is a wry commentary, challenging the authenticity of verse three’s nonsense by pointing out its premeditated nature and deprecating the speaker’s inability to shed his ego. Yang’s poems abound with such restless moves, which Edwards and Xu attentively chart in their translation.

In the same way that Yang’s verses occupy the border between stanza and poem, Yang’s individual poems straddle poem and poetic sequence. These poems have the expansiveness of poetic sequences but the formal homogeneity of individual poems (by being composed entirely of roughly equally sized verses). The greater length of these verse-sequences creates a sense of cumulative impact. For example, the poem “This Country” opens with a one-line verse that throws down the gauntlet, giving a provocative definition of the titular “country:” “A measure of territory, a degree of illness.” What follows is a series of coldly pessimistic epigrams:

Wherever darkness controls the land

Everyone suffers from insomnia

*

They regard darkness as a womb

You bake darkness into black paper

*

Wolves come and come again

Until the sheep are utterly exhausted

The bitter tone and short verse-length remains consistent throughout the poem. The extended length of the poem-poem sequence enables Yang to build a sense of rhythm and lasting duration, impossible in a shorter poem. Yang avoids monotony, however, by skillfully varying the images and metaphors from verse to verse. Later in the poem, the speaker tries to summon optimism with a more hopeful set of images: “Grass grows on earth / The dew gathers on grass / On the dewdrop the sun gleams.” However, the speaker soon undermines this brighter tone, as if unable to believe his own attempt at optimism: “In the sun the black hole grows[.]” The sheer repetition of bleakness, followed by a modulation towards fragile hopefulness, gives the final verse particular power. This has the form of a list poem, which reads like a roster of crimes pronounced by a judge during a sentencing. Each line begins with the refrain “Into,” and most reference a specific tragedy or incident in contemporary China. For example, “Into baby formula add kidney stones” likely refers to a 2008 scandal in which infant formula manufacturers illegally adulterated their product with a cheaper material, leading to tens of thousands of hospitalizations. This last verse is both a compressed litany and a rapid-fire damnation of contemporary China, giving the final answer to the speaker’s sequence-length attempt to define “This country.”

Beneath the scabrous exterior of Yang’s speaker, however, is a palpable sense of loneliness and estrangement. This comes to the fore in the middle section of the book, “This Person.” The poem “To a Poet Who Hasn’t Replied for a Long Time” utilizes the tradition of Tang dynasty poets writing poems to and about each other (the most famous example being Du Fu’s poem, 天末懷李白 or “Thinking of Li Bai at the End of the Sky”). War and politics often forced these poets into unfamiliar lands. Likewise, Yang writes: “To a complete stranger / Everywhere is a foreign country.” Uprootedness mingles with a strong awareness of transience, informed by a Buddhist understanding of emptiness. The poem “Imitation of Autobiography” does not attempt to transcend, justify, scorn, or judge the human world; instead, it ends with a poignant exclamation that simply acknowledges the reality of change and transience:

After removing the hard outer shell

I discover the beauty of humans

All words arrested by a glimpse

In perpetual motion!

In perpetual motion!

It’s a testament to the translators’ choices that Lao Yang’s freedom and urgency leap off the page. Edwards and Xu discuss, in their notes, the difficulties in translating Lao Yang into English. For example, though Edwards and Xu accurately translate the meaning of the line “人 从 众 /众 从 人” with “One of many / many of one,” the pictorial wordplay of the character “人” (person) aggregating and then isolating from “众” (many) is lost. Yang’s use of logographic elements is perhaps the most salient example of the gap between the original and translation, but equally important is the plethora of cultural and historical references. I almost wished for a notes section to alert readers to the depth of Yang’s engagement with Chinese culture, but these freewheeling pieces are probably not the type of poems that suit footnotes. As it is, even readers with a passing understanding of China’s history and geopolitics will appreciate Pee Poems. Perhaps my favorite untranslated reference is the last poem, an envoi titled “Invincible East” (“東方不敗”). The title is loaded with enough irony for the casual reader to appreciate, but “Invincible East” is also the nom de plume of a famous character in Chinese pulp fiction: a powerful but villainous cross-dressing eunuch who is a figure of both LGBTQ+ erasure and empowerment. With characteristic irreverence, Yang parodies China’s geopolitical goals by comparing them to the ambitions of a fictional transvestite. The sheer breadth of Yang’s references, from classical Chinese poetry to pop culture and politics, is exhilarating. But at its core, Pee Poems is a chronicle of how a poet, through his medium, survives and transcends the hardships of displacement and stark sociopolitical realities, without ever losing a stubborn, scabrous sense of vitality.

Angelo Mao is a biomedical scientist and writer. His first book of poems is Abattoir (Burnside Review Press, 2021). His poetry and reviews have appeared in Poetry, Georgia Review, Lana Turner, The Adroit Journal, and elsewhere. He is also a poetry editor for DIALOGIST.

This post may contain affiliate links.