[Lolli Editions; 2022]

Tr. from the Danish by Denise Newman

- In the century since the publication of his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (TLP), which first appeared in English in the summer of 1922, Ludwig Wittgenstein has become, in the words of Marjorie Perloff, something of “a patron saint of artists and poets,” with literary tributes and responses both oblique and obvious (Wittgenstein’s Nephew, Wittgenstein’s Mistress, Wittgenstein Elegy, etc).

- Signe Gjessing’s Tractatus Philosophico-Poeticus (TPP), translated from the Danish by Denise Newman and appearing in English last spring, is the latest instance of a work whose title and presentation mark it as self-consciously “Wittgensteinian.”

- This status as patron saint may have come as a surprise to Wittgenstein, who by most accounts had little to no interest in contemporary art or literature, and whose work seems to contain no clear or systematic aesthetic theory or poetics. And yet it was he who once described his own TLP as “strictly philosophical and at the same time literary,” later prescribing that all philosophy “should really be written only as one would write poetry.”

- Gjessing, in many ways, flips Wittgenstein’s directive on its head, writing poetry as one might write philosophy. The book-length poem is comprised of numbered aphoristic statements, many of which have the same crystalline density—sometimes opaque, sometimes illuminating—as those in Wittgenstein’s TLP:

1.11

Being expects the world, that is all.

3.5111

Transcendence: Holding a space for the world in the infinitely many places.

5.412

The world is the only explanation for the height-differences of the universes.

- At first, I found the book a bit unclear. Or, I was not clear about how it wanted me to read it. I think some of this uncertainty was due to the set of highly abstract and expansive nouns that get repeated throughout: World, Reality, Possibility, Being, the Universe / Cosmic, the Beyond Distance, etc. Reading them as concepts, trying to determine how each was being used or what it signified, or even tracing their relations with each other (is the Universe the World’s Beyond? Is Reality the Possibility of Being?) never held together long; the book seemed to pull away from any systematic sense. And Gjessing’s sometimes playful tone and imagery—“The universe joins the silk team. . . . The world is #1”—made this kind of reading feel pedantic, too literal.

- “I do not think he would love my book,” says Gjessing about Wittgenstein, “but perhaps he would laugh a little.”

- At the same time, the book consciously presents itself as a logical sequence, both formally and in the author’s foreword. The numbered structure clearly reflects Wittgensttein’s famously subdivided sentences, his attempt, writes Gjessing in the foreword, “to create a language of logic.” For her own book, she describes the goal as creating “propositions that self-create into poetry, while still possessing the logical consistency of philosophy,” adding later that the poem can be considered “an accumulation of logical units.”

- I don’t generally think of poems as logical accumulations: logical feels too directive, too closed off, to describe the kind of openness or ambiguity that interests me. Maybe an accumulation in the sense of just before an avalanche. Maybe more like an occurrence, as in how a thought occurs to us, not as the final word but leading to a new encounter somewhere else.

- I’m not here to argue with the book’s poetics, though, only to point out how much the foreword charged my expectations. And I question if the foreword really needed to be there, or whether the reader would be better off encountering the poem itself and working through the meanings of the sequence on their own.

- I’m also not sure how much Gjessing believes in her own declaration of logical consistency. Between many of the propositions I sense the movement of a mind that is less syllogistic and more restless, looping:

2.2

No, no, being disturbs nothing at all.

2.3

Being belongs to no one.

2.4

Being is mitigating circumstances: Nothing. And yet.

- Despite my first uncertainties, I started to find pleasure in the leaps between each proposition, and more so in the little shifts and slips of register (in phrases like “no, no” or “and yet”) that pointed toward a subject or interiority somewhere behind the drafty landscape of this abstract World. In those moments when that subject spoke directly (“Yes, we’re in the world in question, yes, we are in it.”), this pleasure was amplified.

- There’s something similar that happens with the scarcity of concrete imagery. It seems mostly orthodox to champion the concrete (“no ideas but in things”), or sensual, over the conceptual and abstract in contemporary poetry. Without raising the whole debate, it’s worth saying that this rule can and should be pushed against. But I still confess my own relief when bumping up against an object in the language of the poem. To the point that, because of their scarcity, these objects became strangely vivid, almost unfamiliar:

3.6

The world exports a shampoo based on stars and longing.

5.5

I don’t have a steady universe but I have a steady rose.

6.21

Has the world completely given up on transcending without silk?

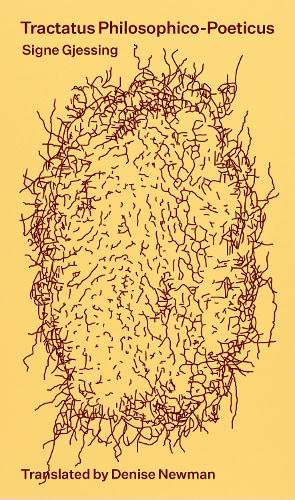

- Silk is one image that threads through the work, surfacing here and there. It wasn’t until after I had read through once or twice that I interpreted the illustration on the cover as a silkworm’s cocoon. Before the title page there is an image of the caterpillar and, on the past page, of the silk moth, completing the image of self-transformation.

- In a talk posted on YouTube, Gjessing comments on the silk motif: “It’s a picture of the poem itself. . . . You can never know on which side you are. So the sentences would be like linen or silk, that you cannot grasp.” I think part of what the poem wants to describe is this sense of grasping an idea or trying to, the slipperiness of reaching after fact or reason, and what gets lost and found in the attempt to speak about the meaning of the world outside oneself.

- At the same time, perhaps through this speaking voice, a self starts to emerge from the tangle of abstractions, one ultimately driven, I think, by questions of love and creativity. And part of how this self is made or discovered is by running into or beyond its own boundaries.

- Here I think of Wittgenstein, who in Philosophical Investigations, published posthumously and seen by many as a disavowal of his earlier Tractatus, describes the process of philosophy as “the uncovering of one or another piece of plain nonsense and bumps that the understanding has got by running its head up against the limits of language.”

- In Gjessing’s case, it might be said that it is the speaking subject of the poem who, in the darkness, bumps against the nonsense of the world, and in that way can start to see a little bit beyond itself.

James Scales is a writer and artist based in New York City’s oldest house. His writing has appeared in Kenyon Review and Yes Poetry, and is forthcoming with The Hopkins Review.

This post may contain affiliate links.