[Coffee House Press; 2022]

Sometime in the fall of 2021, I began watching television for the first time in several years. I started with Station 19, knowing what I could expect and count on from the world of a Shondaland show. What I didn’t account for was that during the reckoning of 2020, modern television shows responded in real time to the fear, sequester, and uprisings that historians will one day look to the art across mediums to understand this uncertain time. What I didn’t expect was the psychological and somatic upheaval created by opening time: How could the sensations of reliving events we’d lived or died through mutate or adapt through fictional stories? Could this re-living of time through fiction annotate lived memory? Fictional time and historical time began to weave together into a consistent déjà vu: “tumbling from dreams/ recalling and channeling/ 4/ black dreams and black time/ in a pandemic/ AFTER GEORGE FLOYD/ what could I gather and make this mean?” Gabrielle Civil writes early in the dèjá vu, her performance memoir and archive dedicated to Black time and Black dreams. The author reflects on memories in a way that both opens and closes the complexity of despair, desperation, isolation, and unknowing many of us encountered during the height of 2020: “constellations of positive and negative time.” In the dèjá vu, Gabrielle Civil finds herself in a similar time loop, rewatching the early aughts TV drama Sleeper Cell, while recounting: “How suffered we all were in all these things, what it was like to live inside them.” This book too, lives inside and outside of time: a portal, a dream, a remembering.

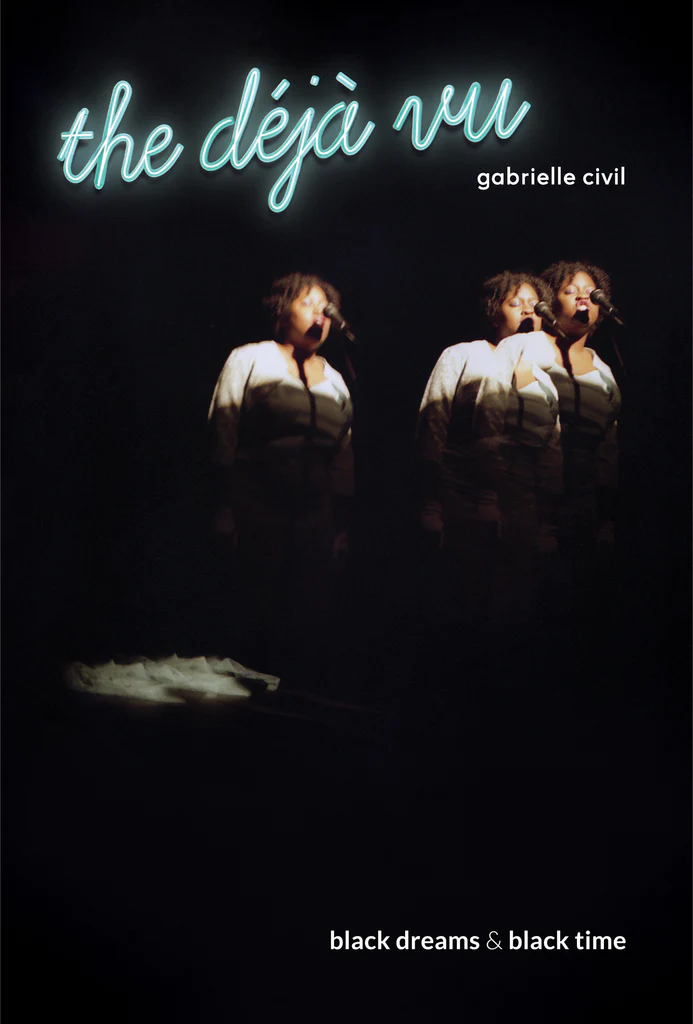

“What if we took our time?” Gabrielle Civil writes. I take my time reading, thumbing, reading backwards, forwards, and sometimes in the middle of Civil’s archive on Black dreams and Black time. I read slowly as if I have returned to the early days of lockdown, delicately, fearfully thumbing pages while in tears. Some of these pages are center aligned and enjambed, others dense blocks of prose, others still snapshots of Civil in performance. In a style I grew to love in swallow the fish, the five meditations that employ many forms to make up the déjà vu are best described in Civil’s words as “a cracking open of space and time/ 8/ an artifact panel/ an electric slide.” As a tour, mapping, archive, and cross-genre reckoning, like her other work, each page of the déjà vu opens up space by addressing time through dreams, memories, archived performances, and visitations to old writings with fresh eyes.

Déjà vu, Civil notes, comes from the French, meaning “already seen.” More than pure coincidence, déjà vu is a recollection of “previous apparitions.” Wikipedia describes the experience of déjà vu as an “anomaly in memory.” If, in fact, each time we remember something we are simultaneously forgetting it or recreating the memory in a new iteration, all memory comes with a dose of anomaly. What we remember and misremember is often how the unconscious tells us who we are and how we experience the world.

This work’s particular form of dèjá vu plays on “An Accounting of Black Feminist Consciousness,” the name of a lecture Civil was hired to teach for a dream job in California early in 2020 before “calamity struck in March.” What I love about Gabrielle Civil as an artist and academic is the way she dances across communities of various types of discourse—uniting scholars, inspiring artists, opening new visions of ways students can archive performance, memory, and voice on the page. In the first section of Black Dreams entitled “(Banana Traces),” Civil gets honest about teaching through a lecture she gave to students in 2008. The preface is a transparent account of her road to academia: “being a professor was never my dream . . . Both my parents are teachers.” I too, never imagined teaching and now laugh when someone puts “professor” before my name, not knowing it’s a title I haven’t earned. Like many of us, Civil questions which job to take, how it will affect her artistry, and how it might make her life more financially sound and expansive: “So I dug in and stayed. I kept connecting the dots between art and life and poetry and performance. I tackled other dreams on my list too.” She not only encourages holding on to dreams, letting them feed every aspect of life, but also looking at the practicalities of living within the academic institution in a capitalist system by revealing the rules and structures inherently counterintuitive to dreaming. She traces the transformation of dreams both in and out of such limits:

In my sixth year at St. Kate’s, in 2006, I earned tenure, becoming one of the school’s first black tenured professors at the age of thirty-two. When does a dream become another dream? That summer, I gave up my car and my apartment, sold all my furniture, and set off on a yearlong adventure. I didn’t follow Josephine’s banana traces to Paris. I went to Montreal, then off to Mexico, Spain, Morocco, the Gambia, Senegal, and back to New York City, and Chicago.

From here, she begins to unravel some of these experiences in a deconstruction of linear time.

Like her other work, the déjà vu oscillates between fonts, layout, italics, serif, and sans serif; as a result, her distinct voice and style rise from the page. In On Commemoration, she begins in Montreal on the fifth anniversary of 9/11 with a paragraph she’d written in 2006. Returning to these pages in 2021, underlined and annotated, she breaks open each memory, responding to underlines with a host of new memories, reckoning with the way space, time, and culture and language has shifted in the last decades. These annotations range from shifts in political correctness and pop culture to the simplest of gut-wrenching sentiments: “2006: ‘What does it mean in public space?’ 2021: ‘public space? Does this now only exist in dreams?’” This annotation continues through Civil’s wandering in Montreal, ending with the 9/11 slogan “never forget.” She notes that forgetting is inevitable: “It will always slip our minds how the world really was, even in the times we lived through, maybe especially in those times . . .” This reminder not only speaks to the beauty of the déjà vu, but its necessity as an archive of not only Black time and Black memory but of an artist who leaned into her deepest calling during the most isolating time many of us have lived through. Through this text, Civil has recorded time, unraveled memory, and reckoned to create a document that is both of its time and of past/future time.

On the first page of the déjà vu, Civil opens with a list poem, “The Déjà Vu,” perhaps both representing the book and the lecture on Black Feminist Consciousness. This poem lives in the ambiguity between contradiction and paradox. Naming what the déjà vu is and isn’t through double negatives, she references the episode of The Magicians, in which Alice is imprisoned in the Library with a greying bearded black man. She asks if he is Santa Claus. In my memory, with a mischievous twinkle in his eye, he says he’s “not not that.” I’m not saying you need to read the déjà vu, but I am not not saying it.

Amy Bobeda holds an MFA from the Jack Kerouac School at Naropa University, where she serves as the director of the Naropa Writing Center and sometimes teaches art, writing, and pedagogy. Her forthcoming book projects include: Red Memory (Flowersong Press), What Bird Are You? (Finishing Line Press), and Blood to Purify the World (Spuyten Duyvil). She is a founding member of Wisdom Body Collective and works in the cross sections of myth, land, language, and menstruation. @amybobeda on Twitter.

This post may contain affiliate links.