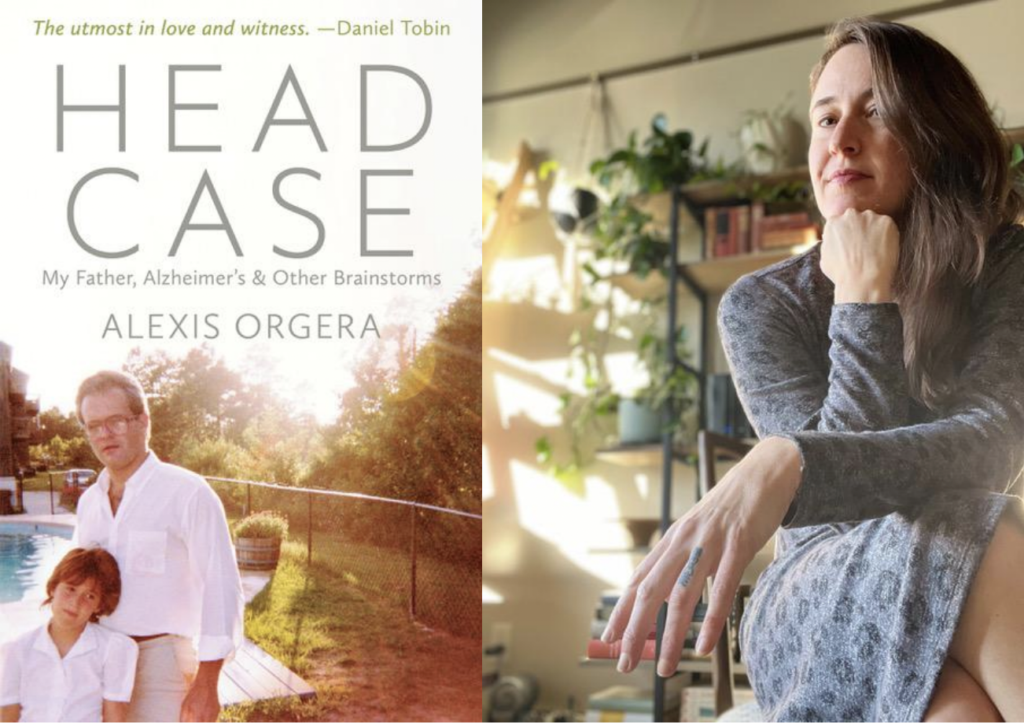

Jeff Alessandrelli: I’ve been a fan of Alexis Orgera’s work for over a decade and I can pinpoint with exactitude the day I first met her: It was on November 3, 2012, when she read in Lincoln, NE, at the reading series I was co-running at the time, The Clean Part. From the start I found Alexis (who, off the page, goes by Lex) to be perceptive, empathetic, and determined. She’s someone that makes those around her better. I realize that’s a cheesy thing to say but it’s true. Head Case: My Father, Alzheimer’s & Other Brainstorms, Lex’s new book, is a poignant and insightful lyric memoir, one that refuses all easy conclusions. Haunting and beautiful, it’s a heavy book. But the language encased within lightens the reader’s load throughout. I was thus excited to talk to Lex about both Head Case and the role that art plays or can play for the average American writer, creating in their average American town, in the midst of very unaverage times.

Lex Orgera: Before we met at his reading series, I’d read Jeff Alessandrelli’s first chapbook, Erik Satie Watusies His Way into Sound, which is this soaring and musical collection inspired by the life and music of Erik Satie, the nineteenth and twentieth century avant-garde composer. I was an instant fan and have loved all of his books since then and up to his latest, And Yet, a work of fiction that lives simultaneously as essay, meditation, and narrative of discovery. In it, Jeff explores shyness—sexual and other—and finding our place in the world as we grow and change. His lens is unique and his voice inquisitive. We’ve been friends for a decade! As we’ve grown up and each changed, Jeff has been a constant, reassuring, and supportive figure in my life. I don’t just admire his writing. He is a determined and kick-ass publisher, a dedicated dog-lover, and one of the kindest, most engaged friends.

Alexis Orgera: In And Yet, you use the refrain “and yet” as a driver, but you also include various and morphing definitions of prudery, as your speaker defines it. How does that repetition and accretion work in the text? Second, the definitions of prudery veer from the dictionary definition to varying degrees. What was the impetus for that? And third, what’s your favorite definition of prudery and/or is there one definition that most describes the speaker, or are they meant to represent an expanding consciousness about the word or the speaker’s worldview?

Jeff Alessandrelli: Heavy opening questions–respect. And to just dive right in, I use “and yet” in the book as a kind of continuation phrase, one that drives the narrative forward, definitely. It’s inserted half-ironically at times, and other times earnestly. The below usage occurs early in the text and somewhat sets the tone for all the subsequent usages. For every assertion or postulation there’s inevitably an “and yet.”

Is it a privilege to write about what one fears most? To freely open oneself up to all attendant interior apprehensions and plug ahead anyway?

*

Rapper Young Thug on his sexual inclinations with former fiancée Jerrika Karlae:

‘“We wasn’t doing it on like no it’s too early to have sex shit,’” he explains. ‘“I don’t care for sex that much. I’ve never actually had sex with her. Never ever. Our first time doin’ grown stuff, she did it. She pulled me to the room and was like ‘come here.”’

“‘Karlae stated that initially she thought he was “weird” for not having sex, but went on to explain why that made her more attracted to Thugga.”’

To be fair, Young Thug—born August 16, 1991—has six children by four different women and in 2018 announced a new name change, to SEX.

*

And yet.

As for prudery—it’s a word that from a young age we’re taught to disdain, maybe even fear. To be a prude is to be fundamentally apart from the social, sexualized world. And yet (sorry) one of the paradoxes of the modern twenty-first century technological world is that the more digitally connected we tend to be, the more physically disconnected we tend to feel. Although And Yet focuses on Millennials, across the board people of all ages are having less sex than they used to. (These numbers were tabulated pre-pandemic also—although that definitely hasn’t helped matters.) I wrote the bulk of And Yet in mid-2018—it feels like a lifetime ago—and in December of 2018, The Atlantic published a cover article by Kate Julian entitled “Why Are Young People Having So Little Sex: Despite the easing of taboos and the rise of hookup apps, Americans are in the midst of a sex recession.” That article got a lot of attention and, although my book was largely written before it came out, And Yet touches on some of the same topics as Julian’s piece, especially in terms of selfhood and shyness.

As for my favorite definition of prudery in the book—it’s probably the below one:

One of my own definitions of prudery entails fucking—fucking girlfriends, fucking boyfriends, fucking spouses and strangers and coworkers and bosses—to mask one’s own confusion and insecurity. This is perhaps an antiquated definition of mine, ill-prepared to advance with the times. Nevertheless it feels true—prudery as hyper-sexual so as to not have to directly deal with what one actually feels, who one actually is.

One of the things I try and play around with in the book is that sometimes the more sexualized someone appears on the outside, the more unsure of themselves they are on the inside. There’s a line I reference from the band Daddy Issues’ song “I’m Not” that encapsulates it: “I feel promiscuous but maybe I’m a prude.” I think a lot of people feel that way at times, whether they’re willing to admit it or not.

Your book Head Case also has a refrain of sorts: migraine. On the one hand, Head Case chronicles your father’s death and dissolution from Alzheimer’s, but simultaneous with that narrative is your own continued entanglement with migraine(s). You couch and reframe what it’s like to suffer from migraine/migraine thinking at multiple points throughout the book, writing midway through the text, “I have always been in the wrong place: crisscrossing the country, looking for something I can’t name on the hazy embankment of an imagined life. I have always displaced myself.” Such earned sentiments are reconfigured, even retracted, later in the text, though, when you state:

For years, migraine has held for me what I couldn’t hold myself—it cupped my anxiety, my shyness, my congenital sadness, my intractable night fears. I had swallowed all of it whole, and migraine had allowed me to release them in violent explosions. Without migraine, I might have melted away.

There are no easy answers or allowances, even for something as seemingly negative as migraine. I’m curious how you arrived at that duality in the book, as well as what the process was like threading your personal, insular narrative with your father’s external one. Did you ever question conjoining them or as you wrote did they simply seamlessly (or otherwise) come together?

AO: I think this idea of prudery as hypersexuality is so interesting. In fact, I think it’s worth thinking about the dictionary definition of prude: a person who is excessively attentive to what is socially acceptable. So if you’re adhering to certain social norms, you could easily be having a lot of sex, which, as you say, could mask how you actually feel—private, shy, reticent.

As with my migraine journey, prudery is a sort of displacement, a scaffolding that both protects us and separates us from ourselves and others.

It didn’t occur to me that “I have always displaced myself” and “migraine held for me what I couldn’t hold myself . . . without migraine I might have melted away” lived in different spaces. But I see it! I’m simultaneously moving and being held in place. I do feel both ways about, well, everything. Being alive really is about straddling those contradictions.

This is part of living with migraine—it’s not a headache but a neurological disorder that fucks you up in various ways days before and days after the “headache” part—you have to learn to live within a certain precarity. I think that’s why Gregory Orr’s essay, “The Edge as Threshold” has always been so meaningful to me. The “ceaseless interplay of disorder and order in our daily lives” is something we all have to figure out, right? The fact that a poet might live in the space between chaos and order; well, that just feels right and good—and sometimes I think migraine made me a poet. During a migraine you live in a liminal space.

So, to answer your question, the duality of migraine is a natural state, and I think that’s why it’s reflected as such in Head Case. Though I might also call it a multiplicity. And that’s why my personal migraine narrative got mixed up in this book about my father’s Alzheimer’s. Let’s face it. This is a memoir about me, not my dad, about how I interpreted someone else’s death through my lens. Migraine’s a part of me, maybe the piece of my narrative that has most defined me, the way I feel my way through the world, the way my brain works. And there are actual memories—Dad stopping the car on the highway so I could throw up during a migraine as a kid. Or during Alzheimer’s, figuring out how I was gonna babysit him when I literally can do nothing if I have a migraine—that link the two.

As I was writing, I frequently asked myself if it was fair of me—if I was somehow trying to compare migraines with Alzheimer’s. In earlier drafts of the book, I think I did try to make a few more direct comparisons vis-à-vis suffering and sick person’s guilt, but that was forced. It’s not about comparison, obviously, but about how interwoven our lives were, inextricably linked via lived experience.

It’s uncomfortable and scary for me to admit that migraines have shaped me, and in many ways limited me, since I was four. There are things I’ve never been able to do, like get through a reading without getting a migraine. We’ve talked over the phone about how we’ve each written books that feel more personal and intimate to share (particularly at readings) than we expected. Yours is semi-autobiographical fiction, mine is lyric memoir. It’s interesting that we both feel naked in front of the classroom, so to speak. I, for one, feel much more fortified in the world of poems, even though poems aren’t any less personal or intimate, just maybe more nuanced and layered.

Can you talk a little more about the source of your own discomfort? I think this is closely related to the discomfort of being (and finding) ourselves in the context of the larger world—the one outside of our heads—which is a topic And Yet also plumbs.

JA: I primarily identify as a poet and definitely feel more at home reading my poems out loud than I do my prose. As a reader of poetry, I’m able to inhabit a certain shifting rhythm from poem to poem and I like the brevity aspect of it too, that I’m not stuck in something for an extended period of time. With prose, that’s not the case. For it to be effective to a listener there also has to be a narrative thread, something for that listener to grasp onto . . . and I’m not always great at teasing those threads out. What represents narrative to one person, moreover, is self-indulgent, rampantly I-centric word vomit to another.

Which brings me to the actual content of And Yet, which I know is what your question is directly referencing. As noted above, I wrote the book in 2018, and I’d be lying if I didn’t think of it as dated in places now. It’s not just Millennials who are having less sex now—it’s Gen Z, it’s Gen X, it’s pretty much everyone. The protagonist’s focus on that generational divide or difference simply reads as erroneous to me now. But, just as important, I do think of the book as fiction. Essayistic fiction, speculative fiction, maybe semi-autobiographical fiction—but fiction. The I in the book is unnamed, and that was a purposeful decision on my part, as I’m really hard on him. (I wrote more about this at Heavy Feather Review.) His geographical trajectory does loosely follow my own, but there are significant differences between the protagonist’s life and Jeff Alessandrelli’s life. Reading from the book in front of people, though, the I character is instantly rendered as me/myself/I—which makes sense. I do that, too, when I hear someone read. I = the reader. And I guess I’ve struggled with that in a way I never have in the past. Being seen in one way and read in another—with my poems, it’s never been an issue.

Since this book is about delicate, oft-not-discussed-out-loud issues (at least not amongst my own friends/family) such as sex and shyness and selfhood, I’ve felt reticent doing readings from the book, to be sure. I’ve done three of them thus far here in Portland, OR (where I live) and they went . . . alright. It’s my own hangup rather than the audience’s. I guess it goes back to what I think Montaigne (maybe?) said, that what he would never say out loud anyone could go in a bookstore and read about in depth. It’s the intimacy of the private page vs. the public world and where the two meet in the middle. When I write most things—and certainly this was the case with And Yet—I don’t think about audience or who might read it down the line. I instead simply focus on articulation and precision. How to translate what’s in my head to what ends up on the page . . . which, as you know, can be inordinately difficult.

With Head Case you’re also speaking for your father in a lot of ways, so that’s an added responsibility and a serious one at that. And Yet doesn’t have that—it’s largely I-focused. Does part of your own discomfort revolve around the fact that you aren’t the only person involved in the story of the book—and that the other main character is your deceased father? Or is it more the intimate nature of the content? Or both of those things, or something else entirely?

AO: Just a couple days ago, when I saw the news that the legend Bill Russell had died, I had a good cry, and then I found myself asking my dad to say hi to him for me. Now, I’m not someone who believes in the afterlife in that way, so it was doubly odd. But, yes, I talk to my dad sometimes, as I do quite a bit in the book. I like to pretend his consciousness is still floating around where he can hear me. I believe in those words A. R. Ammons wrote in “Hymn”: “You are everywhere partial and entire / You are on the inside of everything and on the outside.”

I did have to get over the “are you using your father’s illness as fodder for a book?” stage of writing. The truth is, I’m a writer. I write. I wrote my way through his Alzheimer’s disease, partly as a coping mechanism and partly because I needed something to do with all of the information, torment, and sadness.

I am concerned about being whiny or self-indulgent in memoir, more than with poetry. As you say, what one person thinks is narrative, another person thinks of as word vomit. Though, I’d argue that’s the case for, well, all writing. There’s a more straightforward confessional mode in Head Case—getting anointed by the elder and deacon at a church picnic or my mom having visions of the devil at the foot of her bed for a year or my father smearing shit all over the wall—and it’s a real-time representation of one of the most traumatic experiences of my life, one that led to a nervous breakdown. Painful stuff to share with strangers. I gave a reading in Florida, in the town where my dad was born and died (but he didn’t live there in between), to a roomful of mostly family and friends, and that was less stressful, actually. They, at least, had gone through it with me the first time. My mom interrupted a few times to add a story or disagree with me—which could have gone badly but ended up being quite touching.

I wonder if, in part, the essayistic nature of And Yet makes the divide between the narrator and writer more hazy. Readers are accustomed to this style of writing, in general, being nonfiction, so we just assume the “I” is you. You are messing with and re/mixing genre; we both are. Is this something you set out to do, or did it just happen naturally?

JA: I think at the end of the day I’m simultaneously interested in being open and candid and also protecting myself to the utmost degree. The “essayistic semi fiction”—that phrase was previously used in categorizing W. G. Sebald’s work, not that I’m comparing my work to his (I’m not, for real)—nature of And Yet derived from limitation rather than choice. I can’t write fiction in the way that, say, Ben Lerner or Julie Iromuanya or Janice Lee or Amy Fusselman can, to name four youngish contemporary fiction/hybrid writers that I like. I wish I could, but I can’t. I can’t even write fiction in the way that a competent second year MFA student can. Plot, character construction, narrative arc, and overall structure, the building of tension and the gradual lightening of it—those aren’t my strong suits. I can use a lot of different sources and citations and digressions and I can bend the truth. I can lie, can fib. I can invoke emotion in an autofictional way, even if that emotion doesn’t wholly reside in my autobiography. And, like you, I’m also interested in vulnerability, in linguistically parsing out how and why I feel the way that I do. I admire a thing both deeply felt and seen.

That all being said, most of And Yet was written four-and-a-half years ago and . . . I don’t know. I suppose I simply feel like a different person and writer now. Both the book’s protagonist and its subject matter seem distant, which isn’t to say they don’t seem necessary or important to our current world and contemporary cultural climate. The urgency that I felt when I was writing and revising And Yet in 2018 and 2019, though, just isn’t there for me circa 2022.

You touched on this a bit, but since your Dad’s passing what is your own relationship to Head Case? I guess the deeper question I’m asking is—how important is art when compared with your own sense of stable self and well-being? I think with age I’ve realized that literature isn’t as important to me as I thought it was when I was 22 or 28 or 31. I want to write moving and worthwhile things, to be sure. But, as corny as it sounds, I want to be a good person first. I want to be kind, mindful, and empathetic. If I’m not those things I don’t think writing and publishing matters that much, at least not to me.

AO: I wish I could write any sort of fiction, but I’ve always wanted to write a mystery, like a good Tana French mystery. I have absolutely no grasp of narrative movement. Did I ever tell you the story of the in-progress nonfiction contest Head Case was a finalist in? I got a note from one of the editors that said something to the effect of, “We would publish this if it had more of a narrative arc.” So what did I do? I fragmented it even more. And listen, this wasn’t a conscious rebellion. I simply didn’t know how to do it any other way. Poems teach you to think about shape. Poetry manuscripts too. What’s the implied narrative? That’s what I ask when I’m putting together a collection. What echoes are there? What silences?

My relationship with Head Case is, as I think I said, pretty tied up in the trauma of Alzheimer’s, and of course a whole life history that led up to a nervous breakdown. When I was first writing it, over a decade ago, it was coming home after being with my dad and doing a sort of word vomit on the page. Then after he died, I tinkered with it for a year or two, sent it out for a few years, won a grant/residency where I totally re-envisioned it—during the nervous breakdown and medication that made me feel like I was walking around underwater—and then I put it away. I pulled it back out a few years later, tinkered some more, and sent it out again. Turned it into poems two different times, even tried to sell my publisher on the poem version, but they weren’t interested.

In the end, my relationship with art is that it’s something I want to do most days. Writing, poems in particular, keeps me alert and excited about life. I love the spark of an idea or how words rub up against each other and sing. But I don’t think it sounds corny to want to be a good person first. It makes me proud to call you a friend, and I think you’re making a pretty good run at living that life. And I’m with you—who wants to be a great writer who people will remember as an asshole? As I get older, I realize I’m probably writing to understand the metaphysics of my worldview, which in turn helps me to be better in the day-to-day because, well, we’re all gonna die without knowing what’s next or what’s behind the curtain. I’m in the process of changing careers because I realized a few years back that I thought I was supposed to teach or edit or be a publisher if I wanted to be a writer. But those things can be very draining for me. Actually, a poet friend told me something wonderful once, and I’ve carried it with me. This poet had been teaching for a decade or so and decided to go back to school for a career change. In addition to the more obvious reasons one might pursue a new career, my friend said something to the effect of, “I wanted to find something that would create space for my poems.” On the heels of my forty-fifth birthday, I’m taking a leap.

I think your narrator actually comes to a similar understanding at the end of And Yet. There are a few interconnected epiphanies, but they boil down to the fact that our purpose is to change and grow, and that we’re basically all in the same boat. Our problems are not exceptional. You quote Sir Thomas Browne’s seventeenth century Religio Medici, “Every man is not only himself. Men are lived over again,” which sort of encapsulates both ideas. Interestingly, at this point in the book, you harken back to Mary Ruefle’s daimon, in On Imagination, which you quoted at the beginning of And Yet. Can you talk about what role imagination plays in all of this and what the daimon’s purpose is?

JA: I think that allowing yourself the means to change—the ability to change—is super important, especially as you grow older. Some people burrow into stagnation and/or lack the energy to believe that they can be a different person (or different type of person) in the near or far future. That you’re actively working against those “yesterday is today is tomorrow” mindsets is important. I think it’ll bear significant fruit for you. I’m glad you’re changing careers and still changing as a person generally. Not everyone does that, but, with the passing of time, it’s 100% necessary to make those shifts.

The Ruefle quote that I reference from her chapbook On Imagination reads, in its entirety: “I have lived with my imagination, and in my imagination, for so long that I have no memory of any time on earth without it. It is my daimon if there ever was one.” Ruefle goes on to assert that “The daimon is a kind of twin that prowls alongside, is most often vivid when things are tough, that pushes you toward the life you signed up to live before you fell into the amnesia of birth and forgot the whole affair.”

I think the role of the imagination—in And Yet and all of my writing—is seminal. A lot of writers and artists think this, of course. What’s most important for me to remember is that so much of our sense of self is a fabricated imagination. We are who we believe ourselves to be, and, via changing our belief systems, can renegotiate what we feel and how we act. The nature of the placebo effect has always fascinated me—simply believing a pill or medicine helpful makes that pill or medicine helpful, even if it intrinsically has no healing properties of any kind. Our minds are far more powerful than we give them credit for, at least most of the time. To simply believe in the imaginative power of change is to, on some level, activate that change. I sound like a bad motivational speaker now, but I sincerely believe it’s true. By the end of the text the protagonist of And Yet has put himself in a position to get out of his head and into the active, waking world. This might seem like a small step, but it’s a big one for him.

Final question: I’ve been thinking about time a lot recently, maybe because, like everyone, I’m getting older (hairs that were once black are now gray, etc.). It’s inspiring to me that as you move deeper into your forties, art is as important to you now as it was then. I’ve struggled with that in my late thirties, I can’t lie. The thrill of writing a new piece of work isn’t what it was in my twenties and early thirties. How have you been able to stay engaged and immersed? Via simply writing new things, in new forms that are exciting to you? Publishing different works in different venues? Or? I want the enthusiasm that you seem to have, 100%.

AO: You know, I think getting out of our heads and into the waking world isn’t so easy for anyone, but particularly not for those of us who spend a lot of time in our imagination. That daimon can be a blessing and a curse, if we let it. But, as you say, we are who we think we are (or, as James Allen’s 1903 self-help book is titled, As a Man Thinketh), so to answer your question, I’ve spent the last few years, in particular, actively remembering why I love to write, to make art. I haven’t seen a ton of external validation for my work in recent years—partially this is my own doing, and I also might be writing outside of the zeitgeist of our era—so embracing my own internal validation in the form of joy has been so important. I love to make poems. I love the visceral and auditory experience of it. I love being guided by instinct, which is also duende, which is also collective consciousness, which is also automatic, which is also spirituality. I also have this childlike wonder that, for better or worse, keeps me interested. Also gets me in trouble because I feel perpetually naive! But, yeah, writing new things . . . I have five books of unpublished poems sitting around. I am, if nothing else, prolific. I also enjoy tinkering and revising, but it’s a different muscle. I see that excitement in you in the form of publishing right now, so it’s still there. You’re just using it to amplify other voices right now. These things all come in waves and seasons. I worked hard to reignite the fire after a few years of utter despair. I see you doing important, exciting work, whatever form it’s taking right now.

Jeff Alessandrelli is the author of the poetry collection Fur Not Light (2019), which The Kenyon Review called an “example of radical humility . . . its poems enact a quiet but persistent empathy in the world of creative writing.” Just out from [PANK], Jeff’s latest book is And Yet. In addition to his writing, Jeff also directs the nonprofit book press/record label Fonograf Editions. He’s at jeffalessandrelli.net/.

Lex Orgera is a poet, essayist, book editor, and studying herbalist living in North Carolina. She’s the author of two poetry collections, How Like Foreign Objects, which Ploughshares called profound, engaging, and sincere, and Dust Jacket, as well as a memoir-in-fragments, Head Case: My Father, Alzheimer’s & Other Brainstorms (Kore Press, 2021), a finalist for prizes from Graywolf, CSU Poetry Center, and others that Buzzfeed called “an unflinching look at suffering that is also suffused with beauty.” Recent work can be found in Cimarron Review, Conduit, Hotel Amerika, Indianapolis Review, Interim, Massachusetts Review, Passages North, and elsewhere. More at lexorgera.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.