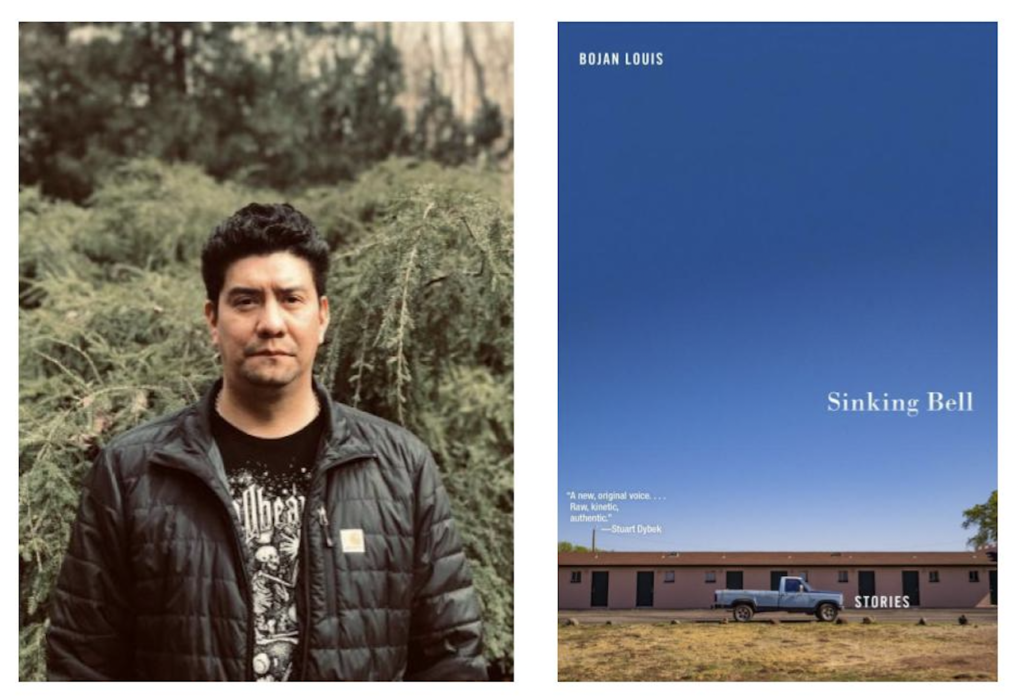

Bojan Louis (Diné) is the author of the poetry collection Currents (BkMk Press, 2017), which received a 2018 American Book Award, and the nonfiction chapbook Troubleshooting Silence in Arizona (The Guillotine Series, 2012). He is an assistant professor in the Creative Writing and American Indian Studies programs at the University of Arizona. Bojan’s new story collection, Sinking Bell (Graywolf Press), will be available in September 2022.

In this interview, I pose some questions to Bojan about the stories in Sinking Bell to better understand the people represented in his book. Metalheads and skilled tradespeople, rich and poor racists, addicts in various stages of recovery, abandoned children and well-meaning families, settlers and Native Americans, the characters of Sinking Bell reflect Bojan’s sharp insights about individuals and their communities. Sometimes cynical, often hopeful, his stories capture the multivariate nature of struggle with realism and empathy.

Bojan’s responses add background, depth, and context to the collection. He was even kind enough to provide a playlist inspired by the book.

Eric Aldrich: Sinking Bell is an allusion to the song “The Sinking Belle (Blue Sheep),” a collaboration between Japanese metal band, Boris, and drone metal legends, Sunn-O))). Several of the characters, like the narrators of “Trickster Myths” and “As Meaningless as the Origin,” and Karl in “Before the Burnings,” describe themselves as metalheads or discuss metal music/culture. These lines from “As Meaningless as the Origin,” for example:

The conversation shifts to metal genres and mosh-pitting, the three of us differentiating the nuances of satanic, black, thrash, satanic-black, gore, gore-thrash, sludge, grind, dirty-black, and experimental. Conroy’s inability to understand anything beyond satanic-black metal bands, generally from Nordic regions, leads him to tell us that his girlfriend is stripping tonight, and that we should watch her because she’ll strip to anything metal, and he wants to hear some metal.

A metalhead reader will understand nuances here that communicate a lot about the characters, information that may elude those unfamiliar with metal subculture. Can you provide a quick primer, or advise readers in some way, to help make the metal nuances accessible?

Bojan Louis: Yeah, the title of the collection is certainly an allusion to the Boris/Sunn O))) collaborative album Altar, and specifically the “The Sinking Belle” track, but it also took inspiration from other things such as the film/memoir, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly. I had a side interest in fashion and fashion magazines, and maybe held some naive illusions that I could write in that world. Completely far-fetched, but inspiration and illusion can be intertwined. I really went down the associative bell rabbit hole, and it’s uncertain whether or not I’ve emerged. But metal music, in its myriad of genres, is a leitmotif that is woven through the collection. Personally, I love all metal but the genres I listen to most would probably be thrash, doom/drone, and black metal. Thrash for the speedy riffs and technicality, doom/drone for its doom and drone, and black metal for the cold, sometimes ugly, and cacophonous sound. As far as a primer is concerned: in 2000 I walked into a record store to buy Deicide’s Insinerhatehymn and the guy on shift was my bro’s, not Biblically but in a Native way, brother and he asked me, “you in it for lyrics or the riffs, the riffs right?” And, of course, that struck and has stayed with me. While I was certainly in it for the riffs, humored by the brutal Satanic lyrics, I realized that there was a fan base who was in it for the ethos and the lyrics. These people are silly or completely crazy, I thought, but they’re probably just like me. Metal is an ever-expanding web, its subgenres infinite, and its fanbase even more complex. The bit of the character’s discussion that you bring up both pokes fun at and celebrates some nuances and subgenres of metal while also pointing out another character’s simplicity or narrow-mindedness, his forte if you will, but which also shows his desire for some kind of connection or acknowledgement. He wants to control the interaction after his comments that lead up to the metal conversation are met with dismissal.

EA: Pair each story with a song readers should listen to while reading or a song you think communicates the atmosphere you feel associated with the story. I can share mine, too, but I don’t want to influence you and share it here.

BL:

- “Trickster Myths” – “Death Blooms” by Mudvayne

- “Make No Sound to Wake” – “Princess Margaret’s Man In The D’Jamalfna” by Coil

- “Volcano” – “Territory (Live)” by Sepultura

- “As Meaningless as the Origin” – “A Sun That Never Sets” by Neurosis

- “A New Place to Hide” – “It Took the Night to Believe” by Sunn O)))

- “Silence” – “Brujerizmo” by Brujeria

- “Before the Burnings” – “Deliverance” by Opeth

- “Usefulness” – “Native Blood” by Testament

For most of these, I wrote what song came to mind. For two of them the paired songs are ones I repeatedly listened to through various drafts, and for one of them I had a band in mind from a specific region and corresponding genre. A Sinking Bell playlist might go on forever.

Flagstaff, AZ, where most of the stories occur, is a border town on the edge of the Navajo Nation and many of the characters in Sinking Bell are Diné (Navajo). The collection shows how Navajo culture interacts with the majority white settler culture of northern Arizona in revealing ways. For example, in “A New Place to Hide,” the narrator recounts how he became an illegal chauffeur when he was twelve or thirteen years old in part because he learned to drive on the rez where it’s common to teach young kids to drive on the open back roads. In Flagstaff, he ends up as a designated driver for his cousin and her friends and eventually a driver for a drug dealing pimp. An underage kid’s ability to drive means something different in Flagstaff than it means in the space around his family’s hogan.

As a Diné writer, do you worry that stories about Diné characters will face a similar risk of being co-opted or harmfully appropriated by a majority white settler reading audience? Choosing Flagstaff as a setting for the collection, and encountering racism and appropriation head-on in the stories, strikes me as a strong hedge against appropriation risk, but I’m curious how you conceptualized this challenge.

I do worry about Diné stories and experiences being co-opted because of the long history of settler colonial culture erasing and presenting hyperbolic stereotypes of Native and Indigenous peoples, bastardizing our narratives and often rendering them obsolete. The soul and meaning ripped from them so only sensationalized tropes remain—artificial artifacts and decoys, stand ins. Tony Hillerman has done this and continues to do so with every film adaptation, despite any efforts to bring in Natives. Why is it so hard to produce Native and Indigenous stories written by Native and Indigenous peoples? Perhaps it’s guilt, lack of imagination, or by using stories written through a lens of settler-colonialism there is a harnessing of power and control where authenticity, reciprocity, or honoring of the past is ignored for brand recognition or comfortability, which is laziness and ignorance. It’s the American way.

The stories in the collection were culled from my imagination and experience, from the stories, experiences, and imagination of my family and my ancestors. The point of view or lens or soul of my work is Diné. There are themes and metaphors of silencing and shame in the collection. Each character is a survivor to some degree, hoping and working towards a better version of life that they have in mind. Native and Indigenous peoples aren’t allowed to struggle and succeed in the American lack of imagination. We’ve been categorized as subhuman, as freeloaders, as pests. The Declaration of Independence calls us “merciless Indian savages.” There’s been no revision, no change, no update. It’s a lack of recognition, reciprocation, and imagination. So, simply existing, writing through doubt and degradation, is a Native way of being in literature.

Long hours, stolen tools, disorganized job sites, racist coworkers and clients, the collection’s conflicts are often propelled by the characters working as contractors. Though many people work in skilled trades, fiction tends to overlook those professions. Why do you think fiction so often ignores trade work? Is it a class distinction—i.e., most who are trained to write well enough to publish their fiction don’t work in trades?

It’s out there, but you certainly have to go and find it. Perhaps readers find the inner machinations of their dwelling and living spaces arbitrary, beneath them, or mysterious and alien. Or, maybe it speaks to one’s anxiety and self-worth not being “handy,” lacking the skills and experience to troubleshoot a residential, or commercial, issue. Maybe it’s not glamorous enough? Also, working in the skilled trades is exhausting, whether you’re the numbskull digging ditches or the master electrician who’s running crews all day, fixing fuck ups with an aged and overused body. It isn’t always easy to churn out a story or novel at the end of the day. Largely why I switched professions or, at least, desired the opportunity to do so. Also, if someone is trained or has trained to write, that doesn’t necessarily mean they’re good or that they’ll be published or whatever. Same goes for the trades too. Some folks have training and years of experience and are still dumb as hell. Same goes for academia.

Both the narrator of “Trickster Myths” and Tony in “Silence” experience relapse into addiction. In “As Meaningless as the Origin,” the arc of the story follows the characters through a drunken, drug-fueled night. Otter in “Usefulness” is an alcoholic. The characters have well-developed backgrounds to explain their substance abuse; at the same time, substance abuse is also a catalyst for the action in the stories. When writing about addiction and drug abuse, do you more often conceptualize the addiction as a symptom of a fundamental conflict or as a cause of conflict itself?

Addiction is a disease, so both. Does a person, or character, know that they’ll be or become an addict? I don’t think so. Each character’s addiction is different and nuanced, idiosyncratic to their characteristics. They are forced to live with it. The narrator of “Trickster Myths” and the character of Tony from “Silence” are mirrors of one another, though each one’s addiction and the substances they abuse are different. One is a divorcee in their 40s forced to eke out a living that doesn’t bring him happiness, and the thing that he believes will bring about his happiness has arrived too late, or he’s too old to attain it, which brings about a relapse. We don’t know how long he’s been sober, but each day he’s on the precipice of using, and he does, but it isn’t a failure, it’s fact and reality of recovery. Tony is also coming to terms with a reason for his substance abuse and he will have to make a choice of how to confront it, the path of which isn’t clear or linear or one of seclusion. He is, or could be, on the verge of paradise. For the unnamed narrator of “Trickster Myths” he’s in his early 20s and in the throes of addiction, has yet to admit that he’s an addict, and struggles being truthful. He’s in denial of his overdose and the suicidal ideations that led him there, even through his narration, and thinks love could save him if he only he could figure out what that is and means. But he’s chasing the wrong thing, placing the illusion of his wellness or self-worth into another person, and blaming the factors of his life that perhaps bring about the most guilt and doubt, which can be one’s family and culture. People in AA or NA might call this a newbie mistake: a guy new to the program who, rather than get himself right, places his focus on another person as the goal of his recovery. He gets stuck in purgatory, ultimately. Otter is in the inferno. Selfish, dumb, dangerous, and self-loathing. Not everyone makes it through this thing.

“Make No Sound to Wake,” the second story in the collection, juggles many interlocking elements and layers. The story is narrated by a ghost invoked by a grandmother telling children a story about the ghost to scare them. The ghost, a woman who cannibalized her own children, remembers when the Diné were displaced by settlers, events that led to her tragic story. The family she observes presents a mixture of Navajo and settler culture that the ghost must try to interpret. The family has their own dynamics between the boy and girl, their mother, their grandmother, and the mother’s new boyfriend. This summary does not do justice to the complexity of the story. As sort of a craft question, how did you approach writing a story with so many moving parts and how did you know when you struck the right balance between each element?

When it felt multidimensional, aligned with the cosmos. That’s the short answer. But a more thorough one might be: multiple revisions and drafts. At one point, the ghost and the Santa stories were separate, written from different points of view, and with a different cast of characters. For instance, the mother told the story in first person and the other was in third person from the perspective of the grandmother. Then, some drafts were from the boy’s perspective in the first person, then they were combined and restructured and repopulated, the end and narrative continually changing. None of it was working until I drafted everything in the third person from the perspective of the ghost. Ultimately, I came to know the terror that the boy felt when I drafted the story in the voice of the ghost. It was probably ten more drafts/revisions after that before it felt right. I went through similar processes with ninety percent of the stories in the collection. For example, I wrote two stories from Bella’s point of view in “Trickster Myths” that went through multiple drafts before I abandoned them in a box. And, I was three chapters into a novel version of “Before the Burnings” from a different character’s perspective before I thought better of what I was doing and returned to the story. I write a lot to cut to a lot and constantly reorganize and reshuffle, saving a working hardcopy of each draft. I like to see my pages bleed with ink. It’s a way to converse and interact with the page in a physical and thoughtful way.

You can read Eric Aldrich‘s recent work in Terrain.org, Euphony, Essay Daily, and Deep Wild. He lives in Tucson, Arizona; ericaldrich.net; @EricJAldrich on Twitter.

This post may contain affiliate links.