[Dzanc Books; 2022]

In his collection Abandoned, the photographer Daniel Regan wanders around the remains of Victorian asylums scattered across the United Kingdom. The photographs still testify to remnants abandoned since the 1980s: beds with their linen, rags of shower curtains, even labelled drawers where the records were once kept. In one photo, Regan (himself a psychiatric patient), poses himself in a grand mirror. As these old asylums gently dim from recent past into history, Regan seems to pose the question to himself: how does he fit within their disappearance? There can be a sense that we “owe” something to this past: There’s something sentimental here, even nostalgic. But also, Regan raises the question of how we fit into the past, how we sit within it, how it sits with us.

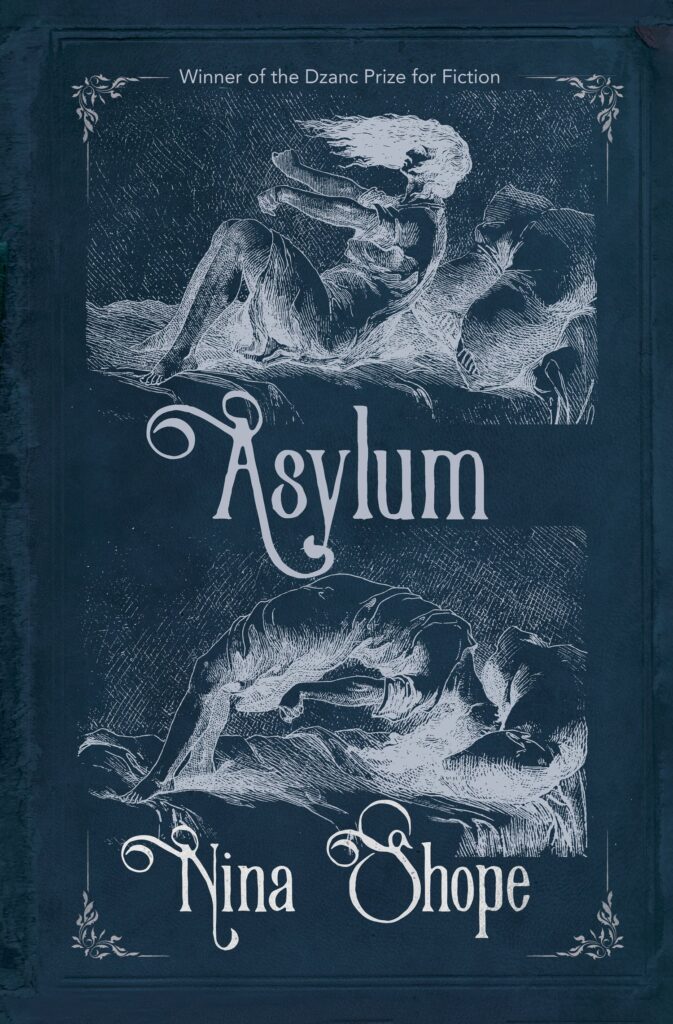

The Asylum of Nina Shope is less one of labyrinthine walls than the asylum as experienced by patient Louise “Augustine” Gleizes. The work is an enthralling, sometimes giddy, evocation of hysteria, the diagnosis with the famous etymology of the “wandering womb.” It is set in the Salpétrière in Paris of the late nineteenth century, at the height of the public fascination with La Grande Hysterie and the ability of psychiatry to explain and define its madness. At the center of this psychiatric circus were the renowned neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot and Augustine, his patient, hysteric, and his muse. Charcot would run famous public leçons, available to the wider public; Edgar Degas, Sarah Bernhardt, and a young Sigmund Freud would be some of the most famous attendees. A central star of these seminars would be Augustine, who would “perform” the seizures, convulsions, and myriad symptoms. Charcot, as a sort of master of ceremonies, would seek to delineate each stage of the hysterical process: epileptoid fits, contortions, “passionate attitudes,” and delirium. In her time at the Salpétrière, Augustine would be photographed, hypnotized, confined. Eventually, she would escape the institution, dressed in the clothes of a man.

Augustine stands, alongside Anna O and Dora, as one of the women used as fuel for the emergence of modern psychiatry. Asylum’s strength is to never look for the cause or an understanding of hysteria, to transfigure into a contemporary case study. Nor does it provide simple solutions to the old question of its veracity, whether hysteria was in some sense “real” or a fiction. We are never quite sure to what extent hysteria emerges through volition or compulsion for Augustine. Shope, instead, gives shape to the psychological force and thrust of hysteria itself.

Shope’s strength is marking the marginal shifts and mechanisms of power between patient and doctor. Who will be remembered or forgotten? Who is the author of hysteria, Augustine or Charcot? Even knowing the eventual outcome —Charcot’s death and Augustine’s escape—the sense of who will “win,” or even what victory would look like, remains in suspension throughout. At points, Augustine is defeated and depleted by Charcot’s actions—when she is too unobliging in the seminars, she is confined; at other times, she is encased, marked around, denoted. Yet Augustine, even in the thralls of hysteria, resists full enclosure: “Her body draped and cunningly concealed—withholding, even when naked, some essential part of herself.” Charcot struggles to control Augustine. In the beginning, he ushers in her convulsions through a touch, as if it were some kind of device. But, later, this touch fails to elicit the desired response. Across the novel, each method of control, from touch to hypnosis to the photograph, is questioned and found wanting, slowly evaporating his desired professional prestige. The novel even hints towards Augustine leading Charcot into pseudoscience and his gradually diminishing reputation, “I encourage you, pushing you towards the margins of scientific study, responding to your most outrageous ideas with alacrity.”

If sometimes even overwhelming, there’s something appropriately heady and disorientating about Shope’s prose. At points, it holds the technical sharpness of psychiatry through sharp metaphors of confinement and control. Noting of Charcot, Shope writes, “in the laboratory, he wires women like lamps.” Elsewhere, Augustine’s hysteria leans to vivid mythology, as she variously figures herself as Galatea, Syrinx, and at her most potent, “she resembles a maenad, plunged in Bacchic ravings, possessed.” The language even seems part of the terrain of Charcot and Augustine’s battle. The technical precision of the Salpétrière seeks to isolate and denote, counting in an epileptic attack: “18 seconds of menace, 10 seconds of appeal, 14 of lewdness, 24 of ecstasy, 22 in which rats are seen, 17 in which music is heard, 13 seconds of snapping in time with the shutter of the camera, followed by 23 seconds of lamentation.” It stands against the visceral warmth of hysteria, which resists the clinical framing, recasting Charcot’s methods in longer and crueller lineages of violence to women in myth, “I am Medusa with her crown of snakes, the camera’s mirrored lens refracting my gaze.”

Why do we return to hysteria? For this book, part of the answer, I suppose, is we’re always called to the past. There is a sense of retrieving the incipient resistance of hysteria, doing justice to a figure in the way she exceeds her psychiatric bracketing, bursting out of the shell of the case study. Therefore, the novel functions as an act of historical restitution. But beyond this moral calling of memory, Shope performs a sort of imaginative retrieval, to understand and provide framing for power and its possibilities. Much like the myths that Augustine evokes, hysteria still stands as one of the foundational mythologies of psychiatry, one that offers the image of an ever-knowing doctor, gesticulating to the patient in hand. “Hysteria” has slowly been erased from the diagnostic manuals, an embarrassment to the profession, a clear vestige of patriarchy in psychiatry’s roots. We might applaud the deletion of such a violent diagnosis—but with such erasures can come a forgetting of a past that could illuminate present acts of violence.

I don’t want to make any wide claims of equivalence—that the abuses of Charcot and the Grande Hysterie are simply repeated in the now. But at a time of mental health crisis, where there is increasing focus on the “expert-by-experience,” there’s something fascinating in a book that leans on the quiet (and loud) violence of diagnosis and psychiatric control. This book speaks to a time where expertise was purely the province of the diagnostician. Augustine’s experiences are ignored and passed over. We’ve seen a recent rise in concern for the voices of those deemed mad and care that must include recognition of their experiences. Augustine’s narrative reminds us of the longevity of this injustice. But also, as she resists, and her experiences slip from each measurement, there’s a suggestion of how patients have always exceeded their psychiatric framing, should we just take a closer look. The chief pleasure of this book is the portrayal of the power play between patient and doctor and to what extent either one can seize control.

Shope leans into the past—its archives and remains, its records, its photos, its drawings, and its statues. She listens, and she imagines. And in a whirlwind of language, she imagines a voice, and the hysteric speaks back.

Jon Venn teaches at the University of Birmingham, UK. His research is about the cultural representations of madness and psychiatry. He is the author of Madness in Contemporary British Theatre: Resistances and Representations. He tweets at @jonvenn.

This post may contain affiliate links.