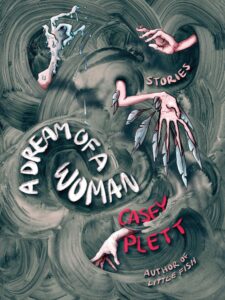

[Arsenal Pulp Press; 2021]

Casey Plett’s A Dream of a Woman is a collection of short stories about transwomen transitioning into early adulthood and seeking relationships, sex, and bodies that align with their sense of self. The stories are character driven, and center the transition of its characters against a backdrop of a country and society that is, likewise, in transition.

In A Dream, Plett lets the characters take over, the language she uses is dictated by their personality, each well-rounded and recognizable. The stories are not all written in first person, but there is a first person flavor to each of them in the sense that the reader views the landscape of the story through one particular character. Plett is able to flesh out each character’s individuality, stressing more on their psychological temperament than their physical characteristics. The reader immediately senses, for instance, Iris’s cheerful gregariousness, David’s go-with-it-ness, and when David transitions, becoming Vera, the reader also quickly notices her new maturity and quiet assertiveness; then there’s Nicole’s loneliness, her self-assuredness and dark humor, Gemma’s desperation, and so on. Each character is unique and complex, which remains Plett’s focus throughout the different stages in the characters’ transitions, in terms of their sex and gender changes, as well as their entry into leading adult lives. Plett knows her characters and she also knows her readers, so she doesn’t try to over-explain anything in the book. There is heavy use of slang that is considered more contemporary, especially to the wider mainstream audience, and may be unfamiliar to people of a different generation, different socio-cultural background, or even from a different country. For instance, Plett writes “Nicole was an honest-to-God switch” when she wants to say that Nicole is into dominant and submissive sex play, and that “Nicole got her D” when referring to her getting sex/dick.

Throughout the book, the author stays hidden, and we read each story in the voice of its protagonist. Take this line: “Also, he’d told Connie he’d gone on hormones and—fucking granddaddy of our patron saint of Mistake Town—had that been the wrong idea.” Here, when reading about an incident, the reader perceives it through David, the character’s voice, and not Plett’s. The reader does not know if the author thinks it was a wrong idea, only that David does so. And David’s voice is very different from the voice of the other protagonists. Here is an excerpt from another story:

Nicole drove home shrieking. Honest-to-God shrieking! How fucking long had it been?! She liked a guy for real, and the guy wanted to see her again. It had been. Such. A long. Time. Since both. Of those things. Had happened. She picked up Burger King on the drive home and ate it in bed watching Netflix, and then glugged NyQuil and hibernated. The next morning, she got ready in a sand-brained haze but was on top of shit the second she rolled in to work. Crushed it. It was a good life. It was a good life.

David’s voice is not the same as Nicole’s, and the reader’s periphery of vision and understanding is dictated by that of David, Nicole, and the other protagonists.

While being unique in characteristics, the protagonists share a similar social background. They share racial (mostly white), age (late 1980s to early 1990s born) and a socio-demographic profile (educated, middle-class, with many growing up in the prairies of the US and Canada, and a lot of Mennonites). As a result, they exhibit a kind of self-awareness and vocabulary to articulate a complexity of feelings and language that is unique to the millennial and post-millennial population growing up within an evolving woke online culture. As someone from the same generation as the characters, reading A Dream of a Woman to me felt like walking round the block from my apartment and entering a Sunday afternoon hang at one of my queer friends’ living rooms, or entering a social media chat. Nicole and David could be one of my Instagram friends, their lives and ways of speaking echo those of others who are living parallel to me. By virtue of its close attention to transwomen inhabiting a specific slice of time and geography—which is roughly between early 2000s to present day COVID-times in North America—the book is an important addition to modern queer literature.

Through the characters, the reader also experiences the external social, economic, and cultural shifts happening in the world around them. When we read about David in his early 20s, we also experience the excitement of Obama’s election, the financial crisis of the 2000s and feel its vibrations amongst David’s circle of friends; and as he grows older, we see the changing discourse and visibility around transness, gender, and queerness. The book, then, also provides a close-up view of modern day America, centering the vantage point of a group that is not part of the mainstream narrative of the country/region.

There are some common threads and recurring themes throughout the book. The friendship between transwomen is one of them. This friendship encompasses intimacy, parenting, partnerships, mutual support, and so much more. It is these friendships that model radical empathy, consent, love, transparency, intentionality and presence. We see it between Cleo and Nicole in “Rose City, City of Roses,” between Gemma, Ava, and Olive in “Enough Trouble,” and between Vera and all the transwomen friends, mentors, and lovers she meets in her journey in “Obsolution.” Here are some snippets of exchanges between Cleo and Nicole as example:

“Then she said, “Do you want to make out?” That was another first for me: the idea that you’d ask.”

And later on in the story:

“She said, What’s your compatibility with bars?

This intentionality of communication, a very delicate and pointed openness. Queers like to talk shit about being terrible communicators, but I don’t think that’s always true. I’m trying to say I loved it when Cleo said this to me.

My compatibility with bars is great, I said.”

These friendships and conversations between the transwomen are also used to untangle tricky knots and to offer meaning and insights throughout the book. Since the narrator never offers her own opinion or analysis of the events, she uses these conversations as useful tools to convey to the reader a deeper meaning behind the plot of the story. One instance is an exchange between Vera and the two transwoman that frequent her bar about gender as a transaction. Here is an excerpt:

“No, she’s right Vera,” said Lucy. “All right, listen, I am old, okay, and I’m pretty done with this shit, but I came out in 2001, right? That time, I was only gendered correctly by the homeless people. . . . Later I realized, that period of my life, they were the only ones who needed something from me.”

“Maybe I mean communication, too,” Anne added . . . Gender’s just a way of getting something across. It’s a way of telling the world what you need. What you want. What you can’t handle. And the world responds accordingly . . .”

Even though the book is itself very specific in its scope, existential realizations like these are universal in their reach. It’s these little lights strung across the book that makes the stories stick to the reader, no matter what their own gender, age, and cultural demography may be. Here is another example: “It made me think: Maybe virginity is real, and it can be lost, but it can also be given. Maybe there’s something beautiful in the concept and not just . . . ruinous. Maybe the truth is just that virginities are malleable, personal, and there are lots of them. And maybe you can even do them over again if you don’t get it right the first time.” This is part of an exchange between Hazel and Christopher, and you don’t have to be trans, American, or millennial to feel a sense of wonder at this idea of renewal of virginities.

Alcohol is another thread that runs through the stories. Many of the characters in the book are alcoholics, at the verge of becoming alcoholics, recovering from alcoholism, or just at different points on the spectrum of an unstable relationship with alcohol. Alcohol is used as a crutch by many of the characters, used to ease into a day, and as a result, many moments and memories black out in the haze of alcohol. Sometimes, the alcoholism is acknowledged, and sometimes not, and repeatedly the reader watches uncomfortably, as the characters drink too much or are coerced into drinking too much.

And then there is sex, the anticipation of it, the experience of it, and the memories of it. Plett is able to show sex in all its awkwardness, hotness and intimacy. Here is one of my favorite scenes from the book:

They get in the elevator. The doors close and Gemma tilts up her chin. “Hey.”

Ava leans down and they kiss. Gemma lifts her hand to Ava’s hair, gently wraps her fingers in it, then wrenches it back. “I missed you, you fucking slut.”

Ava strains at her. “I—”

Gemma pulls harder. “Shut up.”

Ava shakes and Gemma’s clit pulses. Ava’s brown eyes are convulsing pools. Gemma holds Ava like this for a long time. Ava lives on the thirty-eighth floor.

In just a few lines, Plett deftly brings out the personality of Gemma and Ava, their sexual tension, and transfers that tension to the reader. The reader can feel the hotness of that elevator as it ascends through thirty-eight floors with Gemma pulling at Ava’s hair.

Not all scenes are as hot though. Some are uncomfortable, some disappointing (in the way that in-real-life sex can be uncomfortable or disappointing), but Plett tactfully shows the messiness and awkwardness of sex in a way that is very refreshing, and which once again centers the characters and their vulnerabilities, so that it never feels overly sensationalized or eroticized. Sex is not superfluous in the book, but feels essential in understanding the characters’ transitioning into self-affirmation and adulthood.

The protagonists making up A Dream are the so-called “lucky” transwoman—the ones who don’t get killed, the ones who don’t commit suicide, the ones who are not shunned by society. Being mostly white, middle class, and having a community that at best champions them and at worst tolerates them, these transwomen have a chance unlike some others around them to make it. The discrimination, rejections, and disappointments they face are subtle, less obvious. As a result, there is the theme of guilt that the protagonists across stories feel—guilt for not being happy enough or grateful enough. Plett is able to bring out the complexity of this position to the readers, even to the cis readers who may empathize with the well-meaning friend, mother, step-father, girlfriend, etc. that is trying to understand and yet is repeatedly failing to be supportive; as well as feel the hurt of the transwomen experiencing that rejection. For instance, in “Obsolution,” when David asked his mother if he can wear a dress for Thanksgiving to his grandmother’s, and she slowly shook her head no, and was uncharacteristically quiet later, changing the subject . . . I felt his hurt, made worse for the courage it took to ask that question in the first place, but I also understood his mother’s inability to offer that permission. His mother who accepted and loved her son that cross-dressed, but could not rattle the social fabric she is part of by bringing that son in a dress in front of her own mother. The stories show the micro-aggressions and subtler kinds of discrimination that the so called well-meaning friends and family do, the kind that goes unnoticed, unacknowledged by many, and may even be done in the garb of helping, and yet, still cause extreme pain.

“Obsolution” is the longest story amongst the collection, written in six parts, each part alternating with another story in between. It is also the only story where we see the before transition period of the protagonist. The reader is introduced to David, who sometimes wears women’s clothes and underwear, and who then slowly starts to introduce this side of himself in his sexual, romantic, and familial lives. We witness him slowly opening up to the idea of sex change, and also his increasing disconnection with his own body and the joys of the body. And then, years later, when he decides to move to New York and begin the process of transitioning to Vera, the process is gradual, and her reconnecting with her body is also slow. At some point during the story, the pronoun changes; it doesn’t happen after any momentous event, not immediately after she starts taking hormones but just in the middle of the day one day, the pronoun shifts. This echoed the pace of transition that Vera went through, it was not a sudden change from one to the other, but a slow softening, expanding and aligning. Here are excerpts that highlight her gradual reacquaintance with her body.

His internal self was no longer solely some blank oval of maleness; it was like now, suddenly, he had flesh and muscles and he could feel them and it wasn’t bad. His chest became tender, his skin softer. His mood swings were different, organic somehow, like they belonged to the rhythm of the earth…” and then later on when he became she “Oh – it was then she realized – this is what it’s actually like to be touched.

On Goodreads, when answering a reader’s question, Plett said this about the story: “I like to think of Obsolution as sort of being in conversation with the other stories but I think it can work being read either all at once or broken up.” This conversation between the stories is another craft tool that Plett uses to shed meaning to the stories and offer the readers greater understanding of the characters’ inner conflicts. For instance, watching Vera’s journey with her body in “Obsolution” helped me better understand Nicole’s dissociation with hers in “Perfect Places,” and witnessing the “intentionality of conversation” mentioned above in “Rose City, City of Roses” helped me understand what David needed even when he himself was not able to articulate it. Since the stories are written from the characters’ points of view, and because the protagonists sometimes felt distanced from what they were feeling or unable to voice their feelings at the moment, the stories often had instances which perplexed me. And my confusion was a subdued echo of the confusion of the protagonists themselves, and it is the conversation between the different stories that helped dispel it in many cases. The stories in A Dream, much like the characters, thus hold each other up.

In A Dream, the stories do not have a moment of crisis or climax, but just a slow tapering away. A kind of settling. The best case scenario that the characters seemed to hope for, and some at the brink of achieving, was just that—to settle into something ordinary, to have access to ease. The ability to have a job, to afford a place to stay, to go out for coffee and drinks, to have people who are kind to them—these are the basic things that the characters wanted and aimed for. What A Dream does, in the end, is to show the ordinariness of the dream of these transwomen, and how that dream is made of things that cis-men and women take for granted. That even the so-called “lucky” ones still pine for it; and even when or if they attain it, which some of the characters do in a slow and undramatic way, they don’t trust it to stay, so the stories as all good short stories do, do not offer a closure, but just a glimpse into a meandering towards or away from it. The stories in A Dream of a Woman are ultimately about the precariousness and preciousness of the dreams of these women.

Saheli Khastagir is a painter, writer, and development professional from India, based in New Orleans. Her recent work has appeared in Current Affairs, Prairie Fire, The Globe Post, Guftugu, Economic and Political Weekly, The Alipore Post, Nether Quarterly and other publications and anthologies. You can find her creative experiments on her website: www.sahelikhastagir.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.