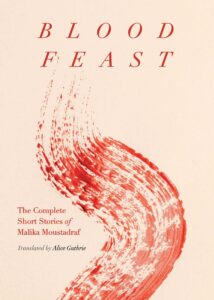

[Feminist Press; 2022]

Tr. from the Arabic by Alice Guthrie

The first thing he did was slap me and say, “The cat dies on day one,” and I knew that, in this context, I was the cat.

Written by the late Moroccan feminist literary activist Malika Moustadraf, and translated from the Arabic by Alice Guthrie, Blood Feast is a collection of fourteen stories that hiss and spit back at forms of unjust authority.

Far from feeling like a one-note, “pussy hat”-wearing diatribe against the patriarchy, however, Blood Feast reveals Moustadraf as a shrewd social observer who manipulates a compelling range of narrative voices and biting narrative techniques, allowing readers to form their own critiques of society. But these stories are not docile. The collection brims with piss and vinegar. Pages belch, fart, sweat, bleed, and moan all over one another, exuding a hot, sticky kind of energy. The characters are regularly nauseous.

Moustadraf shows that what is repulsive can also hold a perversely magnetic allure. “Claustrophobia” features a little boy “savoring his snot feast” on a bus. The young girl in “Thirty Six” is moved to try the dregs of her father’s wretched red wine, which she promptly vomits up. Later, this same girl daydreams about the kofta and onion sandwich she will buy the next day, remarking: “[the foodseller] always looks gross, his big, wobbly belly hanging over his food cart, his fingers up his nose. After he’s done digging for boogers he goes right back to flipping the pieces of kofta and sausage. But it doesn’t matter, his food is delicious.” And in “Death,” the narrator enjoys her dinner as the TV relays news of decaying corpses and decapitated heads, creating a sickening juxtaposition: “I stick my knife and fork into a piece of meat and gobble it up enthusiastically, remarking that the meat is ‘delicious.'”

The simple squeamishness caused by witnessing characters’ enthusiastic consumption of filth-inflected foodstuffs, however, only provokes a fleeting, giddy shiver of disgust. The more deeply unsettling moments in Blood Feast happen when we slip into the deranged perspectives of down-and-out men, who inhabit Casablanca and its outskirts. These characters, known as “slakeets,” or “the bored, unemployed young men who hang around on street corners,” have been disenfranchised by a crumbling state economy, and channel this socio-economic impotence into sexualized rage toward women. In “Delusion,” a man is “filled with rage” at the women he sees in public, who are getting cell phones, cars, and apartments, while he is stuck in his “hellhole” of a house with his parents. Provoked by the “plump buttocks” and “bulging breasts” he sees passing by, the man declares that “what [women] are subjecting us to is violence, that’s what it is. One day I’ll make a placard saying ‘No to violence against men,’ and I’ll march around the streets with it. And they wonder why rapes happen? The world is full of slu–’ He hawked up some phlegm.” In “A Day in the Life of a Married Man,” the male narrator creepily seems to lean out of the page, addressing us directly to say: “Something else I want to whisper in your ear: women are really masochists by nature. Don’t let your mouth hang open like that. A woman loves an evening beating from time to time–these customs have been ingrained in women since the Stone Age.”

While misogynistic ideology is often the target of Moustadraf’s pen, so is the medical apparatus of Morocco. As a person who suffered, and eventually died, from chronic kidney disease, Moustadraf was intimately acquainted with the rank, putrid government hospitals that she describes in the titular story, “Blood Feast.” “You’ll sell off your very bones, your blood drop by drop, to cover the cost of treatment,” remarks a patient in the kidney dialysis ward—a reality for Moustadraf herself, who was unable to fund the entirety of her own treatment. When the narrator of “Raving” awakens in a hospital, she looks around her and asks her mother, “Are we in a butcher’s shop, Mom?”, and in the collection’s opening story, “The Ruse,” a woman slyly comments that “I know a doctor in the building where I work, in Maârif. There’s not one single forbidden procedure he won’t perform. From abortions to hymen restoration, and who knows what other even more shocking things he does in secret too.” The whispered underbelly of Morocco’s medical world materializes in Moustadraf’s stories, in of itself a radical act.

If there is one story that is the collection’s standout, it is “Just Different.” The intersex and/or trans narrator of “Just Different” simply wants to get off the cold street where they are working, and get home to a plate of mussels and hot pepper. Beyond “giving voice” to an intersex and/or trans character (“a first,” Guthrie comments in her Translator’s Note, “in modern Arabic literary fiction”), the story is remarkable for its description of how language can enact violence on the body. Throughout “Just Different,” the narrator has flashbacks to their childhood, when their father “gripped the Quran in both hands and smashed it down onto my head,” for acting like “a fucking sissy,” then forced them to write out “I’m a man” over and over. (All the while, the narrator thinks to themself: “I’m a woman. Man, woman, m–woman”). The flashbacks continue, taking them back to Arabic grammar class, where “they mix up male and female pronouns so their sentences come out sounding ugly, all muddled up and wrong.” The narrator’s violent experience of having gendered language forced upon them is countered through the simple and non-judgmental prose of the story. At the end, the narrator goes home to drink a little beer, and have a plate of mussels with hot pepper.

But Blood Feast isn’t just made up of short stories. Almost a third of the whisper-slim book (51 out of 168 pages) is paratext written by Guthrie. A sweeping Translator’s Note offers a sympathetic sketch of Moustadraf’s life, and gives commentary on the translation challenges posed by idiomatic Moroccan expressions, as well as analysis of Moustadraf’s style and content. Guthrie seems tortured by the fact that she was not able to commune with Moustadraf in life: “I would have certainly visited her in Casablanca over these last six years that I’ve been reading and translating her work, and would have gotten to know her,” she writes, lamenting that she was never able to directly speak to the author. “What would [Moustadraf] want me to say on her behalf? The translator of a dead author faces many such unanswerable questions.”

In order to combat a sensationalistic presentation of Moustadraf’s life (her tragic early death, the alleged sexual abuse she suffered as a child, the famed Moroccan writer Mohamed Zafzaf’s so-called “mentorship” of her work), Guthrie focuses on small, humanizing details about the writer: she had a “ringing, infectious laugh,” “she loved music,” “she was an early adopter of MSN Messenger,” “She loved the color blue.” The effect is simultaneously moving and overwrought, evoking the same feeling one might expect to have while listening to a eulogy, or reading a particularly lyrical obituary, not when consuming a simple biographical sketch. Guthrie seems emotionally close to Moustadraf, lamenting her early death in 2006 as one would the passing of a close friend: “Malika, the dear friend I never had the chance to meet.” It is Guthrie’s explicit goal to enact a “long overdue resurrection of Malika Moustadraf” by means of her re-publication in Arabic, and translation into English.

Guthrie’s devotion to Moustadraf’s work comes through in the energetic language of the translated short stories. Just as Moustadraf carried herself with exuberance and a righteous fire in life, so do Guthrie’s translations exude a provocative confidence, unfettered by mitigating footnotes or obviously filled with glosses (that is, the translator’s explanations of concepts in the Arabic original that may be unfamiliar to anglophone readers, integrated into the translated text). Instead, the language of Blood Feast bites, innervates, and challenges the reader in much the same way that Moustadraf accosted the patriarchal norms of her society.

In addition to the Translator’s Note (footnoted and complete with an extended stream of MLA citations at the end), Guthrie has also created a glossary to illuminate key words from Moustadraf’s stories. For the translation nerds among us, Guthrie’s extensive Note and glossary will titillate and excite. How else would we learn that the phrase “having worms,” in Moroccan slang, means “feeling horny”? What could be more delightful than gaining more context about a “grotesque” parody wedding that occurs between a man and a cat in the story “Briwat”? And I, for one, am very glad to know that “a garish multicolored candy shaped like a giant pole” exists, and is known as jabaan kul obaan in Morocco.

For those less inclined to chuckle with glee at Guthrie’s additional contextualization of Moustadraf’s writing, however, the choice is yours to skip the paratext altogether. These stories stand on their own—delectable bites of literary brilliance.

Anna Learn is a PhD student of contemporary Persian and Spanish-language literatures at the University of Washington. She received her MA in Comparative Literature in 2019 from the Universidad de Salamanca, in Spain. She is particularly interested in short fiction, women’s writing, and translation studies.

This post may contain affiliate links.