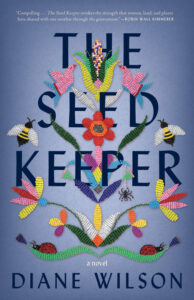

The Seed Keeper: A Novel is Diane Wilson (Dakota)’s first work of fiction in her ongoing career as a writer, as well as an organizer for Native seed rematriation and food sovereignty projects. She is Mdewakanton descendent, enrolled on the Rosebud Reservation.

The story is narrated by four Indigenous women whose lives interweave across generations, but as Wilson emphasized in our conversation, the story is really the seed story. The Seed Keeper is about the loss, recovery, and persistence of seeds as they have long sustained Native peoples in the Americas. And it is about the ways in which Native peoples have been forced to lose, and can gradually reconnect with, their seed relations, in a process of grief and healing.

Wilson and I spoke about how the seed story fundamentally challenges conventional narrative— that is, how seeds reframe the way a story begins and ends, the way a story is spoken and received, how a story reveals its relations, across peoples and towards spaces, and encourages old and new relations through its unfolding. In this way, the seed story is as much historiographic—presenting voices, practices, and past hopes from Native communities violently displaced by settler colonialism—as it is aspirational. Seeds, for Wilson, are an occasion to nurture, and see grow, those hopes, as they are also a means by which individuals and local communities can effectively respond to a climate crisis that has been made to feel too huge to relate to and resolve.

With seeds comes discussion on food, land, Monsanto, bogs, archival research, and love.

Katrina Dzyak: The Seed Keeper has been admired for its polyvocality, as readers follow first-person narratives told by four Indigenous women across several generations. I’m struck, however, by how that polyvocality manifests across the novel’s very first pages. The book opens with a poem called “The Seeds Speak,” and is followed by a “Prologue,” which itself contains the voices of multiple characters who we do not know yet but will soon meet. Chapter One begins in the main narrator Rosalie Iron Wing’s father’s voice, before Rosalie’s voice appears about mid-way through that section. How does that other manifestation of polyvocality, as you position it in this extended opening, disrupt something like origin stories, or complicate how narratives at all get going?

Diane Wilson: Well, I love the way you describe it. It’s always so interesting as a writer to hear your work through another writer’s lens. For me, because that process is so intuitive, I think of it almost like building blocks. There’s a way in which the story ends up starting, when I start writing. I just start, with whatever comes to my mind first, and then I’ll go in different directions with it. It originally was going to be a story told just through Rosalie’s voice, and then I actually developed a writing exercise as a way of trying to really understand and deepen the characters. I come from a background of writing really more in the nonfiction world, so coming to a world of writing about characters was challenging. I came up with this writing exercise of just listening very deeply to the characters. Each one speaks in the first person, and what happened was, different voices emerged out of that exercise. And they were literally different: the tone, the word choice, the character’s voice.

This is something I’ve heard about in fiction writing but had never experienced. So I also applied it to the seeds, because I thought, well, what would they say, what would they want to say? The different voices emerged out of a very organic process of trying to understand what it was I wanted to say about this work, not so much the work of writing, but the work of seeds, the work of cultural recovery, that work of understanding our relationship to plants and animals and seeds. Those layers emerged and I just trusted: I trusted that process and I put it together the way it answered questions for me. And the seeds bookend the story, so that you see, in a way, this is really the seed story. I wanted them to open it and to close it.

The end is a prayer by the seeds, and the prayer is an echo of the form of the opening poem. It is a poem in a different register. In this sense we go back to the beginning, only everything seems different now. I’d like to continue asking about the beginning, especially as a beginning for the story of seeds.

The wintertime is not the most obvious season to open with. You give us a few hints in the first chapter about how to understand the importance of the winter for seeds, when Rosalie’s father describes the season as a time of rest. But then Rosalie herself has a rather vexed relationship to the wintertime in those first scenes. Finally returning to her home on the reservation, she first regrets making the trip during this hard time of year, but only a few pages later, she has embraced the intensity of the winter storm that is unfolding around her. What role does winter play in starting this narrative? What does wintertime perhaps unexpectedly reveal about seeds?

The way we experience seasons here in Minnesota is very distinct. We have extremes of seasonality and there is a way in which seasons also carry kind of an emotional tenor, because of that extreme nature. So I think of winter, it’s that time of dormancy. It’s a time of inward, withdrawing, it’s a contemplative time. There are also important Indigenous teachings around seasons, about the way we live traditionally in accordance with the seasons. And that has to do directly with the foods that we survive on. Winter is the storytelling time. So to see Rosalie in that season is to indicate that she’s come out of what has been her life up to that moment and she has to enter into a dormant period. She has to do that withdrawal, she has to pull the energy back down from what her life has been, down literally into her roots. So it’s very much that metaphor of a tree going dormant, a plant going dormant. And then you’re gathering energy until the next season.

There’s a balance here, where the stories look ahead but are also reflective. Especially with daylight savings, winter can feel like it is itself, time disturbed.

It’s a very long night.

The order in which we do things in any given day seems to shift, even though all the hours are of course the same. Everything feels upended. But that disturbance actually becomes an occasion to slow down, to surrender so to reclaim this complicated time.

It’s a time of such profound transition. A lot of plants just die. They die back or they die completely. So I think of winter as, metaphorically, it’s that small death that happens. Some plants go dormant. Some disappear. And that’s really what Rosalie was dealing with, the losses in her life, and that need to let go of where she has been and what she’s learned and experienced. Grief is one of the subtexts in the book, and so to willingly enter that dormant period, that winter season, allows yourself to also grieve for your losses.

As you have arranged the novel, it is also a story about the role of seeds in how Indigenous women carry and share grief, both generational and individual. And this is also how you introduce love, in opposition to anger. In one scene, Rosalie’s husband and son are discussing their recent investment in the Monsanto-inspired corporation you call Magenta, and how well their farm is predicted to do. Rosalie attempts to offer another perspective to what is becoming corporate agriculture, but her family here ignores her. She says to herself, “Maybe it wasn’t my way to fight from anger. Maybe I needed to learn how to protect what I loved instead.” And then in your Author’s Note at the end, you speak of the Water Protectors at Standing Rock, and how you’ve learned from observing the “complexities of choosing between protesting what is wrong and protecting what you love.” Would you say more about anger and love and how you see the novel representing their dynamic?

The anger is so often at the root of or is part of activism, and there is a righteous anger against injustice that can be very galvanizing, it can be very motivating, it can get a lot of energy into movements. But I think, long term, you have to really look at where your spiritual base is in that work. In order to avoid burning yourself out or re-traumatizing yourself, it needs to come from a place that is restorative. I grew up in the ‘60s and ‘70s, when it was all about the protests, and I was a firm believer and participant in that.

But then going to Standing Rock and seeing how that work was rooted not in protest but in protection, protecting what you love, was kind of mind blowing for me. To me, that’s a very Indigenous way of approaching the work, a way that is sustainable. So if you’re protecting what you love, whether it’s the water, the land, your family, the seeds, you are operating from a place of just doing whatever you need to do to keep them safe. Whereas when you act from anger, then all of your energy is going towards the opposition. Whatever that force is, that is threatening, your focus is there, whereas the other way, it’s with what you love, so you keep your focus on the water here as opposed to your focus on Monsanto. For me, Standing Rock was a huge, huge moment of understanding.

And so I gave Rosalie that question of how was she going to do her work. And then her friend and another of the novel’s narrators Gaby Makespeace, the same question, to come to it from an activism angle. But what’s the cost to your life and your family? Both of them have to answer that in different ways. Both ways are viable, they’re both important, they’re both part of making change and challenging injustice, but you have to find your path. And so that’s what the two of them primarily are showing, the different paths that you can take to being an activist in the world.

By turning away from anger and towards protection, activism dislodges its energy from the framework of opposing parties. This distance, here, becomes an Indigenous space, and allows for the presence of indigeneity as unrelated to any settler colonial constraints. Loving seeds, returning to one’s relations, neither is a response to a settler framework that would keep individuals and relations embroiled within that violent system. Love, as a vector for reclaiming space and community, is an active way of being separate from settler colonialism. But it’s messy, too, since we see Rosalie and Gaby flicker in and out of both those registers of anger and love.

You can go out and protest in a march against Monsanto and/or you can be at home, planting seeds and doing the work to maintain them, and preserve them, and share them with your community. They don’t have to be mutually exclusive, but, where is your foundation, where’s your root in that work?

In not being mutually exclusive, this work ends up demanding relationship-building, whether through the renewal of kinship networks or through other ally-ship networks. One approach needs the other. In the novel, the deliberation between approaches manifests on an individual level, through Rosalie and Gaby. As they grapple with issues of stewardship, family, and politics, they demonstrate how possible it is for a single person to make decisions about issues that reach global scales. In fact, that kind of localized deliberation is critical to sustainable activist work.

Work, in a broader sense, poses another question in the novel. Rosalie seldom frames her gardening as work, but after her first failed attempt to start a garden, she turns to a how-to book and realizes, “I learned that the seeds would be dependent on me, the gardener, for many of their needs. In exchange, we’d have a bounty of food to eat and can. Hmm. That seemed fair, although a lot of work.” And near the end of the novel, Rosalie is planting with Ida, a neighbor on the reservation, and Ida describes how “There’s something so tedious about the work” of gardening. How do you see work signifying in the novel? And, if you are interested in dislodging work from questions about seed stewardship, seed rematriation, and biodiversity in foods, where does work go, in that narrative?

That’s a tough one. I think in a traditional lifestyle, your work was food and your food was your work. Your food and your shelter were your daily commitments and it was easily full-time, to actually feed and clothe and shelter your family. And then we went through this exchange where we no longer pursue our own food and shelter, we do it in exchange for compensation for other work. So one of the challenges in restoring this relationship to our food and plants is, where does that time come from. Because we’ve already exchanged most of that time for compensation, so where does gardening and hunting and fishing, where does it fit, how does that find a place of priority again in people’s lives when we’ve already made these exchanges?

The theme of work too, though, was also a comment on how it is hard work. If you garden, in July, when its sweaty-hot and buggy and you’re out there weeding, it’s just a lot of work. And then somebody comes along, you know, a rabbit, and wipes out your crop. It can just be really tedious, hot, and thankless, when you don’t even get a harvest of it. It’s kind of a commentary that way. But with our focus on climate change and the devastation that’s happening every day, one of the things that I see is this lack of relationship on almost any level with not only your food but with the plants and animals and insects around you. If you don’t have that kind of relationship, then how can you possibly have the motivation to actually steward what needs to be done, to be that protector of the planet? I think we have globalized climate change to a point where we all feel helpless: I’m not going to be able to go and save the ocean, I can’t go there and clean out the plastic, I can’t, myself, do much about the carbon footprint. Maybe one of the reasons why this was allowed to happened was that initial exchange of our labor for compensation, as opposed to remaining in relationship.

So part of the book was to ask, how do we, given our modern-day lives, get back into relationship, and I think the way we do it is on any level. It’s in your backyard first and foremost, it’s what’s outside your door and your window, or on your balcony, if that’s all you have, or if you don’t have any of those options, it’s walking outside and feeling gratitude for what’s around you. To me, this work is all about relationship and that’s really what the book was about.

It seems like any imbrication of work and gardening is one owing to colonization. Work comes into the formula when encroaching communities use agriculture to make claims on land. But work doesn’t exist in this other sense of relationship. Certainly exhaustion and fatigue and worry, all of that is still there, but it needn’t be called work. It’s more dynamic.

One of the most devastating concepts to be introduced to Indigenous peoples was what happened once land ownership was introduced and the impact that had on breaking down a communal approach to food. That was one of the pivotal moments, I think, in history, was that introduction of agriculture, and that was another point I wanted the book to make. The book looks at what was a traditional way of growing and caring for seeds and what that meant to human beings and seeds and all of the related systems. Then it asks, what is the impact of this shift to corporate agriculture? Once you’ve disconnected people from their food, it seems like they can pretty much do with impunity whatever they want with the soil, to the water, to the plants themselves, and that people don’t even know. So you walk into the grocery store and there is your perfectly packaged food item. It’s fine, you take that home. But it’s that relationship piece that brings us back into a sense of both responsibility and agency to do something about it.

And maybe work comes in again, in as far as it’s critical to make that corporate work and the exploited labor that it relies on visible, to reveal those damaging processes for what they are beyond the nicely-packaged foods. With relationships regained as you’re describing, the distribution of food comes more instinctually and sustainably, when, say, there’s an especially large yield from the garden this year and its products should be shared, to prevent rot, or maybe something can’t be canned. In this way, relationships with plants naturally give way to relationships with people too, and this is all separate from notions of work.

And not everybody gardens, but know who’s your gardener, know who’s growing your food and how they’re doing it. That in turn supports those small farmers, the organic farmers, the people who are really trying to make changes. If you take those small changes and then broaden them out exponentially, we would have a movement, we could have a huge impact.

You directed the Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance (NAFSA) for several years. One of the organizations’s goals, alongside seed rematriation and youth engagement, is the reopening of Indigenous trade routes, which returns us to this idea of how strange it is, to compartmentalize space through land ownership. The seeds are a means of those other routes, of Indigenous geographies.

The work with organizations, both NAFSA and Dream of Wild Health and my own gardening, it all went into the novel. I learned so much from the people that I worked with, from the farmers and the seeds and the youth and the elders. They’re the ones who gave me what I needed to know in order to write the book and then I put the story around it. But I couldn’t have written it without spending all those years working for organizations and understanding the impact on the ground, in families and communities, of what this work means. Big shout out to both organizations for doing phenomenal work.

One of the things that did not get into the novel was your bog stewardship, which you talk about on your website. Can I ask you about that?

Yes, well, I used to live in St. Paul, right in the city, in a little bungalow, with a backyard that had a tamarack tree in it. That was thirty years ago, and I had never seen a tamarack tree before, so when I moved into that house, I thought I had this big, dead tree in the back yard, because I didn’t know that tamaracks dropped all their needles. I fell in love with that tree, living there. You know it’s so odd to see a single tree in an urban area. The tamarack in particular tends to live up north and in communal settings but, just to see one in the backyard was very odd, which I didn’t realize until years later.

And then about twenty years ago, my husband and I were looking for a place, we needed studio space, because he’s a painter and I needed a writing studio, and we heard about this place up about an hour north of the Twin Cities and it had a tamarack bog. I just thought, oh my god, we have to move there. So we drove up the next day, right after an ice storm in January, and of course the bog looked like just a whole collection of tall, dead trees. But we bought the place on the spot. [laughter]

The tamarack bog that I live with is one of the original habitats to this land, one of the remaining habitats. It goes back thousands of years. So much of this area is now farmed, but the land that I’m on was a little too hilly, so it was grazed instead. So the bog has persevered; it has remained intact. I feel as the person living here now, that this is my watch, this is my responsibility for ensuring that no harm comes. I don’t really know what that means. But that’s part of the next project I have, which is mapping this land, and trying to understand who’s living here now, how did it come to be what it is after grazing. There’s buckthorn, which is horribly invasive, and there’s another native plant called prickly ash, which is, we’ll just say really enthusiastic, as well.

How does all this relate to the bog and then what can I do as a good guest on this land, to not make things worse, to not disturb it further, even in well intentioned attempts to reestablish balance? That’s the process I’m in right now, is to go out and, with my phone ID app, look at who are all the plants, what are the insects, what birds are still coming here, and then look at each, what do the plants provide, and try to understand the relationships. Again, it’s a system. So, not to do it with blinders on, not to think, I’m just going to remove this, without thinking through, to the extent that I can, the impact. So the bog to me is like the jewel in the midst of this ten acres and I have to figure this out so that I can be a good steward.

Do you envision the project being solely cartographic, or will you include narrative?

It might not be a literally accurate map, it could be thematic, it could be a creative project. It could be a map of relationships. Something I observed today was prickly ash that has completely taken over a hill, it’s almost impenetrable. But what I think it may be doing is actually throwing back the buckthorn. So then it’s like, Wow, I didn’t consider that. We have these two really powerful plant forms. There is a stasis there.

Your description is making me think about how adaptation works. Invasive species adapt to wreak utter havoc but there are also amazing moments of endemic adaptation among organisms and systems, for example, to climate change. The Earth is suffering, but also adapting, enduring, persisting.

You know the monarch butterfly is now on the endangered species list. The fact that we are losing so many species every day, it’s a horrible thing to absorb as a human being and there’s a lot of grief that comes with that. At the same time, all the more reason to be grateful to all of the species that are still here and struggling to survive. What can we do to help support them to make it through?

I’m rooting for the bogs.

You know, once you get hooked on bogs, it’s like being part of a cult. We find each other, the bog people. You know Robin Wall Kimmerer’s books? Aren’t mosses a perfect example of adaptation? This tiny little plant, it somehow finds a way to survive almost anywhere. It adapts more than almost any other species

So astonishing to me about mosses, and also lichen and liverworts, is that they exist everywhere, but they’re different everywhere. There’s very little biodiversity in a single space, but globally, bryophytic biodiversity is almost unparalleled. If bogs and mosses are one kind of space that holds history as your new project is drawing out, I’d like to conclude by speaking about your approach to historical research and archives more broadly.

In your Author’s Note, you mention Buffalo Bird Woman’s Garden, which is a transcribed text, by a US American anthropologist, of Hidatsa Native Waheenee’s descriptions of seeds, planting, and harvesting in the upper midwest. How do you tune into voices that are not always immediately available in the archive, for example, here, through the inevitable cuts, edits, or paraphrasing of a transcription? Or voices that have been either elided or reframed by settler voiceovers or by dominating settler stories? And how have the literary forms you’ve taken up over the course of your career—this is your first novel—help you negotiate this process?

It’s a huge challenge no matter what form you’re working in, to try to sift out what is useful information from what is that subjective interpretation of the viewer. Since those were so often white males, in historical records, then it does become problematic, trying to sift out what’s useable. Back when I was working on my first book, which was a memoir, I had a conversation with a terrific writer, LeAnn Howe, who introduced that concept of “intuitive anthropology.” So you go into a record, you have to look at who’s telling it, what’s their filter, and then what’s not there. So there is an intuitive excavation process that is part of looking beyond what’s present in that record. And merely the fact that that’s who was keeping the record, is a statement.

What I love about Buffalo Bird Woman’s story is that it is such a detailed description of traditional gardening practices. It’s invaluable to me that we have a record of what are amazingly sophisticated tools and practices for someone who understood so profoundly how to work with soil and plants and create your own food sources. So I relied on her to understand, for example how a cache pit was built, which becomes important at the end of The Seed Keeper.

The tricky part for me was verifying that this was a practice that Dakhóta people would have used, and so that took more work. Since it’s fiction, and I’m not having to footnote, necessarily, what I’m creating, if I can at least verify that the story I’m telling is accurate, then I can use her description as a way to flesh out how it was built. It’s just an invaluable tool to see the distance we have traveled in our gardening practices. How much brilliance there is in what she was doing.

How do you go about verifying? How did you know when you would feel comfortable or confident in what you knew about how to build a cache pit, for example?

Multiple sources. That’s where it was helpful having come from nonfiction and creative nonfiction. I do like research, and I did a lot of background research, to ensure that I was telling a true story. Especially if I’m working with online sources, always multiple sources. I always feel better if I can see one thing in more than one place and from more than one perspective.

I think we can frame The Seed Keeper as part of the literary lineage that includes Buffalo Bird Woman’s Garden. One of the problems with asking a question about archives and research, is the suggestion that it’s a done deal, that the archive is a monolithic and closed entity. You and others are contributing to what gets put in there now, but you’re also reframing what has been there all along but not present in some normative way and so not always registered.

That’s where I think the experiential part of working is important, of working with different organizations in the food world and talking to a lot of people, and elders in particular, about what all this meant. Those stories grounded the narrative part of the story, the Native part of the story. Then the research was used really to verify geography or factual information. But the story, the understanding really came from the people that I’ve met.

And those stories don’t need verifying beyond the fact of their telling.

That was their wisdom, and if it rang true to me, then that’s what shaped the story.

Katrina Dzyak is a PhD Candidate in English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University.

This post may contain affiliate links.