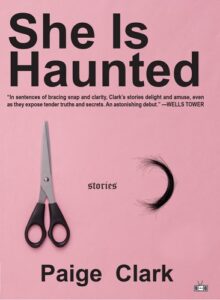

[Two Dollar Radio; 2022]

There is a growing panic among writers that personal endings and world endings are becoming indistinguishable. Climate collapse is compressing conscious experience: To lose something or someone of value to oneself is now to lose the whole world. Millennial literature is quietly declaring that there are no longer any discernible degrees. The death of a loved one is an extinction event; the burning up of a youthful romance is an all-consuming wildfire. It increasingly seems as if life has nothing precious left to offer once its original gifts are spent. No new beginnings lurk on the other side of tragic endings—only endings ever-more catastrophic. The prevailing affect in literary culture generally is metaphysical anguish, even when the product is a joke. The prevailing sense of the world’s justice, meanwhile, is karmic and retributive. Harms get paid with more harms. Death stalks new life.

Paige Clark’s debut collection, She Is Haunted (Two Dollar Radio, 2022), is a fictional study of the never-ending ending, the ending that haunts. The she in the title is a generalized one. Clark’s protagonists are women from different parts of the world, in different stages of life, haunted by different aspects of their pasts, often the deaths of loved ones. Mother-daughter and human-animal conflicts recur across these eighteen stories, as do issues of unwanted pregnancy, erotic frustration, transnational identity, and climate change. The stories come in many genres: parable-like and allegorical, as in “Elizabeth Kübler-Ross” and “Gwendolyn Wakes”; satirical, as in “Amygdala” and “A Woman in Love”; and verisimilar, as in “In a Room of Chinese Women.” For all their generic range, though, Clark’s stories are remarkably steady in affect, drilling the trope of haunting in gaunt prose that is heavy with dread. Even the funny moments, which are many and morbid, reinforce the basic seriousness of Clark’s material. Overall, She Is Haunted is not a can’t-put-it-down kind of book, nor does it pretend to be. It is best taken in measured doses, with careful attention to how Clark expresses her core concerns across genres.

Studies of daughters and mothers, women and motherhood, define She Is Haunted from start to finish. In the parable-like pilot story, “Elizabeth Kübler-Ross,” the first-person narrator is a pregnant woman who “make[s] a deal with God” to trade the lives of her loved ones—namely, her mother’s—for her unborn child’s life. The narrator’s apparently casual sacrifice of the woman who raised her—“I made a good deal,” she remarks—is upset by her dread that God (or nature) will continue to exact a steep price for the new life growing in her womb. This same transactional logic haunts the experience of motherhood in other stories. In “Safety Triangle,” the narrator contemplates an abortion because she cannot imagine bringing more human life onto a sick planet—or being a mother herself when she feels she has failed at being a daughter. Aging, as well, influences how mother-daughter dynamics play out in these stories. In “What We Deserve,” an elderly mother named Rosa starts to grasp the simple physics of the world’s justice—that those who harm shall be harmed in turn—as she slowly loses control of her mind. Rosa learns this harsh truth through her relationship with the daughter who arranged her end-of-life care. When it comes to her daughter, Rosa thinks, she never gets what she wants—fidelity, security, love—but she always gets what she deserves, comeuppance for her past sins as a mother.

Erotic frustration is another motif in the lives of Clark’s characters. The allegorical “Gwendolyn Wakes” follows a 34-year-old woman named Gwendolyn who works for an Australian government bureau that counsels people in romantic crisis. When Gwendolyn, a virgin, has a brief liaison with a coworker, she finds that her first real pleasures are thwarted by her lover’s fetishes and the bureau’s frigid management of human longing. In “Private Eating,” a woman pretends to be a vegetarian to impress a handsome doctor but indulges in animal products when she dines alone. Her feigned dietary ethics mirrors her feigned attraction to a man in whose company she is not herself. Underlying Clark’s portrayals of erotic out-of-jointness is an analysis of how history and cultural politics haunt desire. “Lie-in” and “In a Room of Chinese Women” are stories narrated from the perspectives of diasporic Chinese women—Australian and American, respectively—in long-term relationships with white men. In addition to unpacking the nuances of interracial partnerships, these stories explore the rivalries and solidarities the narrators feel with the other women in their partners’ lives and suggest that history molds human desire as much as nature does.

One of the more intriguing patterns in She Is Haunted is how Clark’s protagonists often turn to animals to mediate their existential and interpersonal conflicts. For the narrator of “Elizabeth Kübler-Ross,” animals are treasured companions that become convenient objects for blood sacrifice when God demands it. In “A Woman in Love,” a bitter divorcee clones her husband’s dog as a way of holding on to their shattered marriage. And in “Safety Triangle,” the narrator lists caged zoo animals among the primary victims of a California earthquake. Clark seems preoccupied above all with the glaring ironies of human-animal relations, how they mix care and neglect, love and utility. Such ironies are palpable in the author’s frequent use of morbid idioms that reference animals. For example, in “Safety Triangle,” the phrase calling a wolf a dog is a euphemism for downplaying the human causes of climate disasters that disproportionately victimize non-humans. The (intentionally incorrect) association of elephants and peanuts is used to great effect in that story, too. Comparing her own anxieties about pregnancy to those of zoo elephants who refuse to breed in captivity, the narrator imagines the baby in her belly as a peanut, then later asks her partner if he knows that elephants do not eat peanuts. Clark’s witty wordplays show how animality haunts humanity, not just at the margins of civilization, but in the very grain of language.

Haunting is the signature trope in Clark’s collection as well as the essence of its literary form. In every story, no matter the narrator, past time always trespasses into present time. She Is Haunted mixes elements of melodrama—the mother-daughter psychodrama above all—into a traumatic temporality in which the past is never-ending. In “Why My Hair Is Long,” for instance, the narrator’s estranged mother haunts her “like a phantom limb, the body’s memory of what is lost.” Note the choice of tense here: is lost as opposed to has been lost or was lost. The past is always right now, and the narrator demonstrates this by ruminating on an episode where her mother gave her a violent haircut that she cannot put out of mind.

It is in the unsettling finale of She Is Haunted—which, due its more methodical execution, reads as if it may have been conceived before the other stories—that the book’s core concerns fully express themselves. Titled “Dead Summer,” it follows a daughter’s coming undone after her mother’s death. “Lose your mother and you lose everything,” the narrator declares, just before giving up everything to make the declaration true. What this young person seems to desire, above all, is to be completely alone with her loss, to forget all other worldly attachments but the one that matters to her the most. It is almost as if losing everything helps her to actualize herself, to become one, at last, with her departed mother. In her grief, she asymmetrically resembles the dread-filled narrator of “Elizabeth Kübler-Ross,” who is willing to sacrifice everyone around her in order to bring a new life into the world. What sort of future awaits human beings who treat their moral interests with such melodramatic seriousness and casual neglect at the same time? I pose these parting questions fully cognizant of the collection’s climatological subtext. Paige Clark’s haunted characters find themselves in a situation much like ours. The stories in She Is Haunted speak directly to our generational panic of feeling traumatized by the past and myopic toward the future.

Kelly M.S. Swope is Visiting Professor of Philosophy at Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio, where he lectures in political philosophy. He hails from Granville, Ohio.

This post may contain affiliate links.