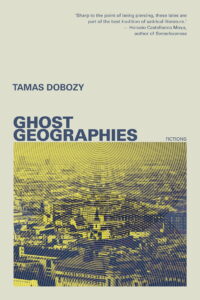

[New Star Books; 2021]

The characters and places Tamas Dobozy charts in his short story collection Ghost Geographies are haunted by ruinous ideas just as they haunt the ruins of the twentieth century. Dobozy follows ruined countries, ruined ideologies, and shattered people shambling through the ruins of what they’ve built, dwelling in the collapse of their imagined utopias. His displaced, disoriented characters, who have lived through wars, upheavals, revolutions, and state failures, stand at the end of history and speak to our own turbulent times, aptly labelled by the crew at Bungacast as “the End of the End of History.”

In the opening chapter of Winesburg, Ohio, Sherwood Anderson’s classic short story collection, we are introduced to an old writer who dreams up characters made grotesque by the truths they gobble up. He imagines a world full of independent truths, Platonic ideals just living their lives until people come along, snatch them up, and in turn both corrupt and are corrupted by these truths, now twisted into falsehoods. A similar process besets the absurd utopianists in “The Hobo and the Archivist,” the first story in Ghost Geographies. The story follows the bumbling archivist and devout communist Adelbert Wuyts as he leaves Belgium for Budapest in 1976 at the invitation of the General Secretary of Hungary. Excited to see his ideology flourishing in Hungary, Wuyts, ever the good archivist, only regrets that he left behind his card catalog, a Borgesian fantastical cabinet that contains everything ever known about the cities of the world. This cabinet, and the longing for the histories it houses, haunts him throughout the story.

His hopes are soon dashed when he arrives in Budapest and isn’t greeted by the General Secretary and a limo but grime, sleet, and the smell of piss. Ernyő, a fellow utopianist whose utopia sounds something like the Third Reich, leads Wuyts to a dumpy apartment where four more utopianists are holed up with bad caviar and even worse champagne. Rather than entering a fraternity of like-minded communists, Wuyts is crushed to discover that each utopianist is a monomaniac for their own utopia. Gyüri is a libertarian, free market fanatic à la Milton Friedman. Gábor is a monarchist. Katalin, the most sympathetic utopianist and eventually Wuyts’s lover, imagines a utopia with no other women, only men and her—an erotic utopia. The final member of the welcome party is a hobo named Szép. He’s described as filthy, smelly, “like a mound of garbage piled in the corner.” Szép, unlike the utopianists living for castles in the sky, is grounded, embodied, the human creature we are, as opposed to the lofty ideals we might imagine or wish ourselves to be. Szép represents our messy reality.

Wuyts is stripped of his passport and his Belgian identity. He’s given Hungarian papers instead. Clinging to his dream, his truth, despite the absurd mystery of his circumstances and the accompanying glimmers of self-doubt, he recites the merits of a true communist state to his fellow utopianists, who greet him with blank looks or barely suppressed laughter. Time passes. The utopianists meet to hold court, trot out their tattered truths, and keep each other company in their irrelevance. Szép attends these meetings too, present but apart.

Katalin, sensing Wuyts’s disappointment, suggests Szép as a way to bring Wuyts’s cherished cabinet, his archive, from Belgium to Budapest. Szép, she claims, unlike the other utopianists who envision utopia, is utopia—utopia incarnate in the smelliest hobo in the Eastern Bloc. And the plan works, in a manner of speaking. Szép, slowly, piecemeal, over years, smuggles bits of Wuyts’s beloved cabinet to Budapest for him, even as Hungary is changing. The 70s turn into the 80s. Communism seems about to collapse, though Wuyts can’t admit it to himself. He remains in the dark about who brought him to Hungary and who has been paying his bills. But Szép reveals that Wuyts isn’t as alone as he feels because utopianists abound:

Szép waved his hand at the city. “They’re all over,” he said . . . “But you’ve never met any of them.”

Wuyts willed himself not to believe it. “Why are you telling me this?”

“The cabinet,” said Szép. “You’re the only one with a cabinet. It’s like a big balloon. Until you grab it. Then it turns into an anchor.”

“Whatever,” said Wuyts. “It’s the only thing saving me.”

The cabinet is Hegelian history—intelligible, progressive, and painstakingly catalogued by Wuyts. He enlists it in service to the dream of his utopia, to justify it. But, as Szép implies, the utopia’s attractive logic also leads to its rigidity and is used to justify all sorts of horrors. Wuyts, like any good ideologue, can’t let it go.

The utopianists’ final meeting occurs as communism collapses and Szép appears in a tuxedo with the last pieces of Wuyts’s cabinet. Szép reveals, finally, with a note of bitter triumph, his utopia: “In my perfect world everyone will know they’re going to get what they want—and they’ll be stuck in that moment, before it actually arrives, forever.” The utopianists, like the rest of us, are forever stuck in a present not of our making, in the throes of history, dreaming about some brighter, impossible future.

Throughout the collection, characters struggle with their histories. In “Ray Electric,” a wrestler executes a daring escape from Hungary via a hot air balloon only to end up in Canada not free but trapped in a sordid cycle of cage fights and increasing isolation. In “The Glory Days of Donkey Kong,” an old man, a former Hungarian judge disgraced for sentencing innocent people to their deaths for so-called political crimes, frequents an arcade purely to pick a fight with some teens and to avenge himself upon someone. History repeats, recurs, and refuses to stop or be forgotten.

Some of Dobozy’s characters make history, others imagine it. Almost all are victims of it. None more so, perhaps, than Sándor Eszterházy, the dead protagonist at the heart of the eponymous “Ghost Geographies.” Eszterházy was an outsider artist of sorts, a Sebaldian Hungarian refugee who ended up stateless, freezing to death hunched over one of his artworks, a “map” he made on the floor of a condemned house in Fort Erie, Ontario.

Eszterházy recalls Sherwood Anderson’s writer, who dreamt up “the Book of the Grotesque” and wrote, “the grotesques were not all horrible. Some were amusing, some almost beautiful.” Eszterházy’s maps might fall in the latter camp. He mapped the derelict, forgotten, neglected, and ethereal. The maps are eclectic to say the least: drawings on coasters, watercolors, a whole slew of different styles, perspectives, and media that, taken together, “become the old man’s atlas, a country real enough in its details, but whose overall parameters are spectral.” One imagines a cross between the collages of Kurt Schwitters and the spiritual unfoldment in the landscapes of Joseph E. Yoakum. However, Dobozy describes Eszterházy’s final map not so much unfolding as spilling across the floor, “as if it had been poured from his eyes.” Eszterházy is another visionary utopianist, another grotesque.

Not much is known about Eszterházy, though the narrator, inspired by a colleague of his who curated an exhibit of Eszterházy’s “art,” tries to discover what he can. Eszterházy, like Sebald’s Austerlitz, was an orphan of World War II. He was a stateless wanderer who year after year crossed back and forth between the US and Canada, mapping these derelict spaces, the sorts of spaces the narrator feels drawn to. The story ends with the narrator talking to a kid at the site of Eszterházy’s death. Eszterházy had promised to take the kid to the places in the maps. The narrator doesn’t have the heart to tell the kid that Eszterházy’s country, his world, his utopia, disappeared with him. That, ultimately, no matter how well we map these utopias, no matter how firmly we cling to our truths, they never existed as we imagined them. But that doesn’t stop us from imagining. Better, brighter, more perfect futures are springing to life in billions of imaginations at this very moment. Each lays claim to the arc of history and tries to own the march of progress. And, perhaps, one day . . . .

Kent Kosack is a writer, editor, and educator living in Pittsburgh, PA. His work has been published in Tin House (Flash Fidelity), the Cincinnati Review, the Normal School, Hobart, and elsewhere. See more at: www.kentkosack.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.