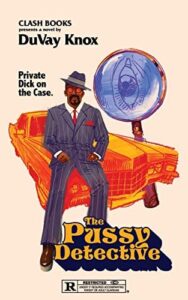

[Clash Books; 2022]

“I don’t write literature. I write shiterature,” says DuVay Knox, the author of The Pussy Detective, a novel spawned out of any number of genres, not one of them that you would call literature.

The story is an occult, erotic mystery featuring a detective, Reverend Daddy Hoodoo, who specializes in locating the metaphysically missing genitalia of women. You might hear that and think of Ishmael Reed’s blisteringly funny, smart, revisionist history/mystery Mumbo Jumbo, about the dance crazes of the 1920s that grew out of the warring impulses of negrophilia and negrophobia. Or the Illuminatus! trilogy by Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson, the (satirical) detective story that explores the clandestine wars of secret societies shaping America through an odd collection of anarchists traveling the world on a golden submarine performing occult sex rituals. (Key line: “Nobody wants war any more, but wars keep happening.”) But you’d be wrong. Those are postmodern romps for people who get all the references. Knox writes for people who, unlike you and me, don’t get novels written for them. Pussy Detective is an entirely different sort of writing.

Try this. Read a line like:“You probably wondering how I got into Finding Lost Pussy,” or “I don’t eat when Im getting ready to Rescue Pussy,” or even, “She had given her HEART without Consulting her PUSSY!”That’s right, The Pussy Detective is a novel concerned with the erotic. Daddy’s occult learning has outfitted him to be a kind of sex guru, especially concerned with helping women establish right relations with members of the opposite sex and themselves. The inciting incident here is a woman, Abysinnia who can no longer masturbate, a serious case. She’s lost the knack after getting with the dubious Greasy, someone who peddles consciousness while practicing fake sex magic, taking advantage of women’s desires for sexual and spiritual liberation to prey off and exploit (“sexploit,” that is) them. All of this is delivered in tweet-length sentences, instantly digestible and quickly readable. Of variable alternative spellings and capitalization schemes, Knox might have even written it on his phone. If Audre Lorde could make the case for poetry on scraps of paper in the free moments between work shifts, then Knox should be free to define a novel as looking exactly like this.

But if that is not sufficient description, it is important to understand that this is not literature in the traditional sense. That is, it’s not written by an MFA graduate, and it’s not written with the educational elite in mind, and certainly not with their tastes. Let me get at that difference: One time I took out from the library a thick, 400-page hardcover art catalog, Walls Turned Sideways: Artists Confront the Justice System, expecting, as you might be, some PEN-America-Amnesty-International-style, liberal-left document of all the pain and suffering of the wrongfully imprisoned transmuted into expressions of untrained-yet-emotionally-expressive and really quite deep art. What you get, although they don’t put it on the website, is some of that, and then a lot of very finely rendered pen and pencil drawings of nude women. A drawing of a nude woman, I must imagine, does a lot for you when you are imprisoned. And the difference between highbrow expectation and reality is where you find shiterature.

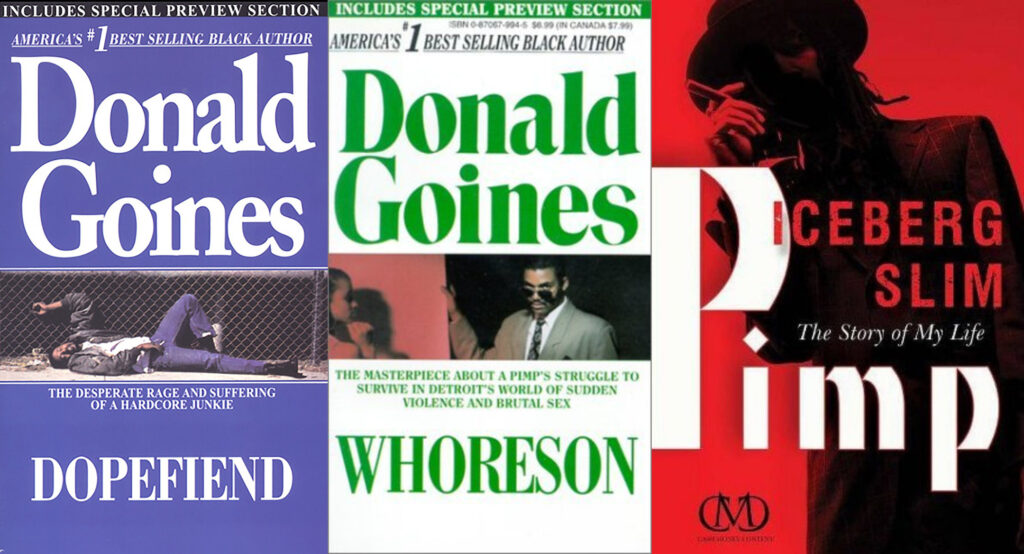

The Pussy Detective falls into the lineage of crime fiction by authors like Iceberg Slim and Donald Goines, Blaxploitation writers whose work trafficked in and troubled tropes about an underserved market of Black readers. Slim, the pen name of Robert Beck, was a pimp who began his career at eighteen and continued on for the next two decades until a prison stay prompted him to change occupations. With the help of his wife, Betty Shue, Beck wrote Pimp, published in 1967, a visceral work sharpened by Beck’s idiomatic and lyrical form of expression. He published three more books in the next four years. Goines, on the other hand, was from a middle-class family, and it was his time in the army that introduced him to heroin. He supported himself through various kinds of activities frowned upon by the state, leading him as well to prison, where he read Pimp. Between 1971 and his death in 1974, Goines wrote 16 books, including titles such as Dopefiend, Whoreson, and Inner City Hoodlum.

Slim and Goines’s books were rough poetry, dealing with sex work, drug use, and violence in cold and grim fashion. To channel James Baldwin a second, for the liberal reader this presents a dilemma: Despite the gratuitous violence and exaggeration, he suspects secretly that Black life might really be like this. So he is fascinated and fearful, wishing to ameliorate the hardships of the ghetto while also hoping nothing about its every glistening detail ever changes. When Slim and Goines were first writing, the hopeful mirage of the Civil Rights era had begun to melt away in the heat of long, hot summers. Municipal services often just let the fires of urban uprisings smolder, and some cities, like Detroit, were never rebuilt after rebellions. White fears, followed by white flight, mounted. The post-liberal cities of the seventies, hollowed out of people, stripped of services by a diminishing tax base, became ripe grounds for white fantasies. Holloway House, founded by two white men, Bentley Morris and Ralph Weinstock, and the main publisher of both Slim and Goines, could furnish the material.

Holloway came to an important revelation. After the success of Slim’s Pimp, they realized there was a market for what Matthew Teutsch calls specifically “Black sleaze.” There were other pleasures to serve than the voyeuristic interests of the newly-suburban white and different standpoints from which to appreciate some stories being told that featured Black protagonists living and existing in exclusively Black worlds (albeit and especially if heightened ones). Literary critic H. Bruce Franklin testifies, “In all American prison literature, nothing has quite the same effects as these novels, which have converted untold numbers of nonreaders into addicts craving their next book while also transforming their vision of themselves and their world.” Whoreson is a kind of Harry Potter for the literarily disenfranchised. This is the most exciting prospect of Knox’s writing. He doesn’t care about a mainstream reader, isn’t even thinking about them.

Instead, Knox knows his audience and writes what he believes they want. From there, he’s got his own thing going on, which is to say Reverend Daddy Hoodoo is a bit of a freak. See for example this rumination after he hears Patti LaBelle come on the radio:

I knew one thing: Cant-A-Bitch OUT-SANG Patti.

Maybe ARETHA.

Butt Patti range was off da charts.

Made mah Dick Hard.

Actually, a lotta things made my Johnson hard.

But only as it related to Women n shit.

What can I say?

I’m built funny.

Maybe all erotic novels are really treatises on sex, but Knox’s even more so.

As the above passage indicates, he takes care to underline his heterosexuality, and his worldview breaks down neatly. He takes the troubled women, while his sometime-partner, Madam X, treats the men afflicted with the same condition. So far, the twain don’t meet. Karma is also a sexually transmitted disease, Daddy informs us. You even have to be careful who you hug, because love and affection have as much to do with the psyche as with the body. That feels about as good an insight on sexual relationships as anything else I’ve read, so good luck to you all.

Daddy’s philosophy seems to be a keyed-up, dramatized version of Knox’s own, and, in comparison to some of the authors mentioned here, an essentially benevolent one. Depending on how seriously you take the theft of the spiritual essence of one’s genitalia, Knox’s women are not subjected to the kind of violence they are in the novels of Slim and Goines, a kind of generic brutality meant to show the stakes are high, the world is hopeless, and that you are reading the grittiest of crime fiction. Neither are they marginal characters, as with Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo or Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson’s Illuminatus! books. Knox is essentially, even devotedly, concerned with treating women right, and in calling out those who don’t. Especially interesting is that the novel draws our eye to someone who is abusing women in the name of a particularly modern form of male-feminist hucksterism.

The most dynamic parts of the novel are when Daddy is up against a clearly defined opposing force. This might be the spirit of Abyssinia’s runaway genitalia, who has to be convinced to return to her host’s body or the ghost of Greasy still lingering on in Abyssinia’s (spiritual?) body. But Daddy is the kind of all-powerful protagonist that, philosophy aside, needs something to struggle against. And while he is often paired off with important women characters, his relationships with them are always so copacetic, so frictionless, that Daddy doesn’t get a ton of definition—and neither do they. What happens when a woman doesn’t agree with him? Detective stories are uniquely positioned to tell stories not about all-powerful men reveling in their all-powerful capability but about the way circumstances reveal their powerlessness against the powers-that-be. Weary doggedness faces off against unknowable and overwhelming odds and, as often as not, loses whatever it values most. Knox gives us a happy ending.

Still, I’m hooked enough by the setting and the audience to hope for more. What would it look like for a sex-positive male to explore and come up against the male chauvinism of the so-called radical left? What would the good Reverend Detective do when set against an institution like a church, with its layers of reinforcing secrecy, mystification, and bodily puritanism? Knox’s protagonist is also just so rigidly heterosexual—it’s not clear to me how deep this goes, if he’s homophobic as is suggested, and if there is some narrative angle that Knox will open up on this, if so. Maybe the philosophy he is hawking is more of that old male/female-two-halves-of-the-whole-universe line, but I hope it isn’t. There are all kinds of sexual cosmologies to draw on that don’t strike the world down the middle. What would happen if Madam X went out of town and Daddy Hoodoo had to help one of her male patients? In what ways would that test his self-concept? Or rescue a trans woman’s spiritual genitalia. God knows there are enough demonic forces marshaled against them in shamelessly un-secret cabals that reach from pulpits to statehouses. And who wouldn’t love to see Daddy, righteously fluid, swing into the rigid sex/gender system with the kind of horny canniness he brings to his straight jobs?

Promisingly, Knox cites women like Zora Neale Hurston and Gayl Jones as influences, and I would want to see how that interest carries into his work. I’d also love to see him write a sex scene that is as fucked up and raw as something in a Gayl Jones novel. Another good sign: His work has been championed by independent women-led presses. 2021’s Soul Collector came from Marjorie Steele’s Creative Onion Press, and The Pussy Detective is out of Clash Books, run by Leza Cantoral and Christoph Paul.

Knox himself has an eye on format and audience, with plans to serialize future works and collect them in short, pocket-sized editions. In an essay on the perils of publishing in a literary marketplace dominated by white tastes, Kiese Laymon writes, “I’ll get my work out to my folks and if they want more, I’ll show them. If not, that’s fine. I’m a writer. I write.” New forms of writing are born when an author has the faith that an audience exists for that work and has the courage to act on it. Well, here’s “shiterature”; not a genre in the proper sense, shiterature plays with all the trash that Literature has defined itself against.

Daddy Hoodoo states, “I always said the Clit Lives in da Hood butt I aint never been afraid to go there.” I may not be the audience Knox has in mind, but I want to see him go there and keep going there and bring his freak sensibilities, too.

M. Delmonico Connolly is the author of Ronnie Spector in Rock Gomorrah (Gold Line Press, 2020) and an editor at the Albright-Knox Art Museum in Buffalo, New York. His research explores the crossroads of journalism and leftist organizing, and his writing on pop music, comics, and the subliterary—usually through the lens of race—can be found on LARB, SOLRAD, and The Comics Journal.

This post may contain affiliate links.