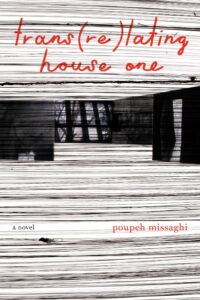

[Coffee House Press; 2020]

Poupeh Missaghi’s debut, trans(re)lating house one, takes place in the aftermath of Iran’s 2009 election. The novel tells of a woman who searches for the statues that are disappearing from Tehran’s public spaces; it is part detective story of the missing statues, part documentation of the murdered and disappeared protestors, and part theoretical explication of what it means to witness and remember and translate. While it is relatively simple to name these three parts, it is more difficult naming the total effect. These three parts — maybe it’s better to say they are impulses — manifest in ways that make my heart race.

It is rare I encounter a work that is so formally perfectly realized of itself that it is almost painfully exciting to read; the space of the page becomes increasingly charged from the precise and repeating shapes. I’ll show you: We encounter, in right-aligned double-spaced text, a compulsively followable detective story told in the present tense with a “she” as the character. The next page over, we encounter a similarly searching “I” who is asking questions about what the “she” is seeing even as the “she” is a careful (re)construction of the “I” via (re)search in an uncanny present tense:

The city is losing its statues. I read about this online. It feels surreal,

as if nonfiction is already fiction. I want her to map the city, to

follow the trail of the lost statues. The statues disappear. The public

spaces once dedicated to their bodies remain void. The city has

more space, less space. I want her to find the bronze bodies. Find

the bodies.

I excerpt it here to show the left-aligned shape of the text, its single spacing; the short declarative style of sentences, the movement of the present tense that is simple (“the city is losing its statues”) that then becomes anything but when the fact that the narrator right now “read[s] about this online” gives way to the narrator’s desire about the third-person woman (“I want her to map the city, to / follow the trail of the lost statues”).

The fact that the “I” and the “she” cohabitate even momentarily signals the kind of layering that happens then dissipates, quickly, as if it didn’t even happen. The previous page lets us encounter this woman in her own present tense:

She turns around. Everyone is looking outside. Everyone is

looking inside. Nobody is saying anything.

The text becomes double-spaced and right-aligned for the duration of the page. And the difference — the double-spaced to single-spaced; the right aligned to the left-aligned — repeats across pages, almost as if the text is inhaling and exhaling.

This breathing of the text — we can think of this inhaling and exhaling in terms of the ribcage, the lungs — is actualized in the ideas it contains. For example, early on in the book, a left page — the “she” realm of a present tense novel — gives the reader a scene where a cow has been sacrificed in the city: “They have the cow sacrificed. A sacrifice / for gratitude, for thankfulness.” (I use the virgule here, which is usually indicated for line breaks in poems, to retain the shape of the text). The line of thinking of the people partaking in this sacrificial ritual is that “The city will be cleansed of addicts, / vagrants, beggars, peddlers, of the vicious and immoral” and so “Better days will come. / The city will become pure.”The next page is right-facing, single-spaced, and is the contraction of sacrifice, so that it immediately expands the book into its own ideas that the killing of the cow brings up to the narrator:

Sacrifice for purity.

Sacrifice of one body for another. One of flesh. The other of brick

and cement and asphalt and glass, of gray and gray and green and

red and orange and green and gray and gray and black.

Sacrifice as ritual.

Repeating “sacrifice,” the act that occurs in the world of the “she” and the novel, the narrator on the right-hand side of the page is led to consider it as a ritual and “rituals need to be carried out in open spaces.” This page gets charged by this staccato repetition until an explicit question forms that almost feels, in comparison to the fragmented phrasing, like a backformation of legato thinking: “What does it mean to sacrifice bodies for a greater cause? To perform / rituals to create meaning? To symbolize life? Or death?”. My sensitivity has been so charged, as a reader, that it feels like the only way to express this quality is to mix my metaphors: backformation being a linguistic phenomena and legato being a dynamic in music. Additionally, it feels wrong to quote the text without showing it in its layout on the page. Such laying out is crucial to the creation of Missaghi‘s invocational inquiry in us as readers.

This inquiry is continually charged by the scene work in the world of the searching third-person woman and the other kinds of page-shapes that are written in such spare language and layout. As a reader, I constantly feel the pinch and see the glint of the imagery which then takes on a different intensity as the form on the page shifts to draw me into a new angle. For example, after the above scenes about the cow sacrifice and the speaker’s musing, the reader gets a page that looks like this:

Missing Statue (13): The Calf

Location: the Calf, along with the parent

cow, had lived in front of the school of

veterinary medicine at the University of

Tehran since the day the school opened.

Date Gone Missing: Spring 2010

The cow remains standing.

The minimal reportage here reinforces my sense of all that is not only unsaid but unable to be found out in order to then say it. trans(re)lating house one moves forward in these different shapes, on the heels of the third and first persons who are in pursuit of themselves in a way that efficiently explodes expected sentiments. The shaping of the text in its alignment and its spacing is one of several ways that tran(re)lating house one sensitizes readers to the searching for answers about the statues that have disappeared which become shadowed by grief, unease, and resilience.

In other words, it is through this manipulation of textual space that the book enacts its journey. “How can the book remain a book of journey not destination?” asks the narrator. The constant and steady shifting in and out of a few modes develops a strong rhythm of telling, documenting, and asking that becomes the journey itself. The reader witnesses it in psychologically real time.

This interchanging of impulses, of sections, is useful in another way too: some of the sections are detached documentations of individual deaths, using the language of a report form that you might find in a coroner’s office. Such detachment increases how brutal the murders seem. These documentary sections end in the language of the obituary (”so and so is survived by two brothers,” for instance) and again, there isn’t a lot of overt poetic intervention in these sections. The prose is so tightly controlled that the appearance of an “and,” for instance, in a sentence can become overwhelming. We read, here, in a narrow column form text that is choppy and fragmented and detached. No “ands” are given. To somehow name a connection that an “and” implies would be to hint at a kind of logic. The withholding of “and” thus creates a powerful restrained painful feeling, so then, to suddenly read an “and” in the context of a familiar closing sentence (“He is survived by a brother and two sisters and maybe a father”) becomes sharply devastating. I am describing one instance, but the maneuver of “and” — of showing and pointing to connection — becomes a powerful way that Missaghi controls the pathos of the text. It gives relief to hear an “and” in one way, but the fact — and it is a fact — that we readers haven’t received them before in this context becomes linked to the justice that has been withheld as well. To hear an “and” is a merciful sign of logic.

trans(re)lating house one, as a title, already suggests a care about the composition of words, coining a new one with a parenthetical “re” embedded so that the reader can’t ever forget the core reflex that “re” suggests about repetition and the distance that a subject travels from itself before it can no longer be regarded as part of itself anymore, part of the original source, home, where the subject comes from: “house one.” “Translation” as a word on its own doesn’t cut it — it must be or can be modified, almost playfully or insistently, with that “re”. When I slow down to close read these textual elements, I mean to signal how the title prepares us what to expect in terms of what it will focus on, but while the theoretical dimensions are clear and exact, no paratextual analysis prepares the reader from the most astonishing part of this book as a reading experience; its power comes from a page-by-page careful basis.

Nathaniel Rosenthalis is the author of two forthcoming full-length books of poetry. His debut, I Won’t Begin Again, won the 2021 Burnside Review Press Book Award, selected by Sommar Browning. His second collection, The Leniad, will be out from Broken Sleep Books in the UK. He is also the author of three chapbooks, including the 24 Hour Air (PANK Books, 2022). He lives in New York City, where he teaches writing at NYU and Columbia University. He is also an actor and singer who recently made his Off-Broadway debut.

This post may contain affiliate links.