[Catapult; 2022]

In a defining scene from E.J. Koh’s 2020 memoir The Magical Language of Others, the Korean-American poet and translator recalls an early poetry teacher asking what she is called by her Korean mother. Koh replies by pronouncing her Korean name, Eun Ji, which she has mostly abandoned in America for her Western name, Angela. Koh feels a sense of affirmation when her teacher insists on calling her Eun Ji. The author is estranged from her mother, who left for Korea with her father when Koh was fifteen. After this pivotal moment, Koh starts to work through poetry, and eventually translation, towards forgiveness and love for the mother who abandoned her, as well as towards a recovery of the Korean language that had once been so distant. Importantly, the aforementioned poetry teacher played an influential role in this, giving Koh not only the gift of poetry, but also the generous space for redefining herself as Eun Ji, her mother’s daughter and, therefore, as someone capable of forgiveness. As Koh writes in her memoir’s note on translation, “Eun Ji is the name [my mother] gave me. Eun, as in mercy and kindness, closer to mercy than kindness.” The reclamation of her Korean name not only exposes a self that has been suppressed, but also opens her to the possibility of expanding her capacity for love.

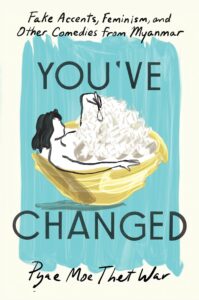

The definition of a self suspended between Western and Asian cultures, whether through naming, painful coming of age, or the rebellion against staid cultural values, is the unifying theme for the essays in the bracingly honest, irreverent collection, You’ve Changed, from the Myanmar debut writer Pyae Moe Thet War. The work is both a bold renovation and essential contribution to the tradition of Asian writers with ties to the West examining their fractured identities within racialized societies through essay collections of memoir and cultural analysis, including Jay Caspian Kang’s The Loneliest Americans and Xiaolu Guo’s A Lover’s Discourse. However, one of the work’s important distinctions is that unlike the first-generation American Kang or the Chinese transplant Guo, who focuses their self-examinations within Western societies, Pyae charts her changing identity as an outsider in both Western and Asian spaces. The author is alienated both as a Myanmar woman in the U.S. and U.K. during her young adulthood, and as a Western-educated individual in Myanmar when she returns for visits and ultimately settles in her hometown of Yangon. The author describes her negotiation of the cultural prescriptions imposed by these spaces through a doffing and peeling away of identities until she approaches something resembling an authentic self. These roving essays capture the complexities of identity formation by evoking the process of self-definition in all its precariousness, despair, and joy.

An essential feature to Pyae’s exploration of identity is the undoing of oppressive social conditioning. This arc is most markedly demonstrated in the opening essay “A Me By Any Other Name,” in which the author grapples with retaining her Myanmar name in Western spaces — an experience paralleled in E.J. Koh’s memoir. Pyae writes of the self-hatred suffered as a child when her Western teachers stumbled over the pronunciation of “Pyae” during roll call and how she once desired a Western name, one easily said by Western individuals, such as Lizzie (after the American TV character Lizzie McGuire). The author maps a trajectory from this initial point of shame over her name to fervent espousal in her late teens to fraught affection in her twenties. Pyae’s anxiety over her name reflects not only an acute consciousness of Western social norms, but also their internalization, such that they begin to police the names she can call herself and therefore her self-definition. This insidious conditioning is made evident when the adult Pyae considers being called “Moe,” a character in her name, because it would lessen the stress in many social interactions with non-Myanmar individuals. She ultimately rejects the idea — the name “feels strange and jarring, like a stranger calling me by a childhood nickname” and affirms that “I am Moe Thet War and I am Pyae Pyae, but I am not Moe.” Pyae’s reclamation of her two Myanmar names, as opposed to a single, abbreviated Americanized one, represents a decolonizing of the mind — in the words of the Kenyan novelist and theorist Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o — in that it reverses an internalized notion of Western cultural and linguistic superiority. This shift in thinking manifests in essays such as “Tongue Twisters” and “Myanglish,” when the author chooses to leave Myanmar characters untranslated, therefore resisting their Westernization. For Pyae, the defining of the self requires the dismantling of Western modes of thinking to create space for the embrace of those of Myanmar and the emergence of her own body of values.

A number of these essays, like “Myanglish” and “Paperwork,” also portray arcs of decolonization through the author’s reclamation of Myanmar as home, whether physically or metaphorically. In “Paperwork,” Pyae describes her painful realization that she cannot stay in the UK and marry her British boyfriend, Toothpick, because it requires the sacrifice of all connections to Myanmar — most importantly, her family. She writes of the strong but silent love from her father: Pyae can “feel his presence when he’s entered the same room as [her] without ever having to turn around.” She ultimately chooses to return to Myanmar because she cannot bear losing this presence. The relearning of the Myanmar language and the decentering of English in “Myanglish” also occurs as the author seeks to bridge a loss of understanding that has opened between her and her grandmother, A May. Therefore, in both essays, the possibility of loss of connection to family strengthens her sense of rootedness to Myanmar. She reclaims her connection to Myanmar through the affirmation of her love for family.

Though Pyae does learn to accept elements of Myanmar culture, like her name and its language, as central to her identity, she rebels against other elements she finds repressive. The author’s education and early adulthood in the West allowed for the assimilation of feminist ideas and the lucidity to question patriarchal or otherwise stifling views entrenched within older generations of Myanmar women, including those of her mother and grandmother. In the essay “Laundry Load,” Pyae wrestles against the sexist Myanmar concept of hpone, which refers to the belief that men possess an innate power that can be sapped if their bodies or clothing contact women’s garments, especially underwear during the washing of laundry. The author argues that hpone wrongly ingrains into Myanmar culture the idea that men are innately superior to women, while also according greater love and respect for its men. Though the adult Pyae recognizes the practice as wrongfully sexist and opposed to her feminist principles, she confesses a sense of guilt and shame one of the first times she explicitly acts against the rules of hpone by washing her underwear with her boyfriend’s in the same load. She reflects on her underwear rubbing against her boyfriend’s as a “betrayal of my whole culture.” Therefore, for Pyae, the unlearning of a lifetime of cultural indoctrination requires the overcoming of cycles of stigma and shame. The essay’s eponymous “load” playfully refers to the burden of guilt carried by the individual who renounces one of their culture’s core beliefs. Ironically, the author learns to accept the betrayal of her culture as essential to her womanhood and identity. Pyae’s freedom from noxious Myanmar cultural beliefs involves both the reprogramming of the mind, in her words, and the fortification of the heart against all the guilt entailed in turning one’s back on one’s culture.

Throughout the collection, the author’s escape from cycles of stigma also frees her from traumas that limit the defining of herself. Perhaps one of the most traumatic of such cycles occurs in the essay “Swimming Lessons,” which describes a paralyzing intergenerational fear of swimming and water in Pyae’s family that originated with the accidental death of the author’s youngest uncle, Zan Lay, by drowning. At around fifteen, the author starts suffering from a mental illness, a form of suicidal ideation she characterizes as constantly trying to stay afloat within the sea, while wavering between “actively wanting to drown and fantasizing about what it’d be like to drown.” Pyae suggests that her mental illness is an incarnation of her family’s intergenerational fear of water. Her condition is exacerbated by the fact that topics like death, mental health, and water have been stigmatized by her family and never discussed. To cope with her mental illness would require Pyae to speak up about her mental health within a safe community of friends, therefore breaking a cycle of stigma and fear. Throughout the essay, the author skilfully couples two narratives of recovery: coming to terms with her mental illness and learning to swim — “I felt determined to become good at swimming and comfortable in and around water, so as to break this chain of fear that had run through my family. When it came to my own mental health, too, as scary and difficult as it was to research and speak up about what was going on in my brain, I knew I had to, or else even water didn’t kill me, these thoughts very possibly could.” Through this method, Pyae demonstrates the importance of actively facing fear, whether of speaking aloud or drowning, for undoing intergenerational cycles of suppression.

This idea echoes E.J. Koh’s gloss on her poem, “American Han,” in which she describes grappling with the Korean concept of han, an inherited feeling of deep grief and sorrow produced by historical trauma. Koh explains it is important “to know it’s not han’s suffering to be avoided, it’s to be faced, because on the other side of that is joy.” That “joy” represents an acceptance of a fraught but essential part of identity in the forms of han for Koh and mental illness for Pyae. For both Pyae and her grandmother, who slowly immerses herself in a pool of water in the essay’s glimmering final image, the confrontation with trauma, a proximity with loss and suffering, allows for its healing and the possibility of transformation.

Many of these essays, like “A Me By Any Other Name,” “Swimming Lessons,” and “Htamin sar chin tae,” trace arcs of transformation and recovery of suppressed elements of identity. However, Pyae subverts a tidy resolution of her identity into a concrete definition through sly self-commentary on the writing process. Towards the end of “A Me By Any Other Name,” the author writes in a sort of coda of constantly revising earlier versions of the eponymous essay, which she first drafted in 2012. In this passage, which was incorporated many years after the first draft, the author expresses greater self-acceptance but admits to circling back to the essay and her position on her name: “‘What do you think of my name?’ I asked [my boyfriend] recently, as I was revisiting this essay in its more recent incarnation. I was trying to formulate my own collective thoughts on the topic at this moment in my life, and had realized that it’d been a while since I’d sat down and thought of my name for an extended period of time.” Pyae’s constant revisiting of the essay suggests the unsettled nature of her view on her name and her identity. Her postmodernist coda, a second ending attached to what seemed like the more conventional ending in a previous version of the piece, recurs in an essay on womanhood, “good, Myanmar, girl,” and disrupts the finality of both essays. Therefore, Pyae’s formal innovation establishes both identity and the essay itself as unfinished projects, in an ongoing state of flux.

Though You’ve Changed suggests the limits to change, it nevertheless cultivates an identity that is free-roaming within the liminal zone between the West and Myanmar. In this sensitively observed collection, the freedom to define oneself is achieved not only through the rebellion against cultural constraints, but also the embrace of the provisional nature of identity. Pyae’s fractured self is healed not through solidification into something permanent but a reassembling into a more peaceful existence with her disparate parts. As Pyae writes of the supportive but changing communities surrounding her, we “adapt and evolve, hopefully into better iterations of [ourselves].”

Darren Huang is a Full Stop Reviews Editor and writer based in Manhattan.

This post may contain affiliate links.