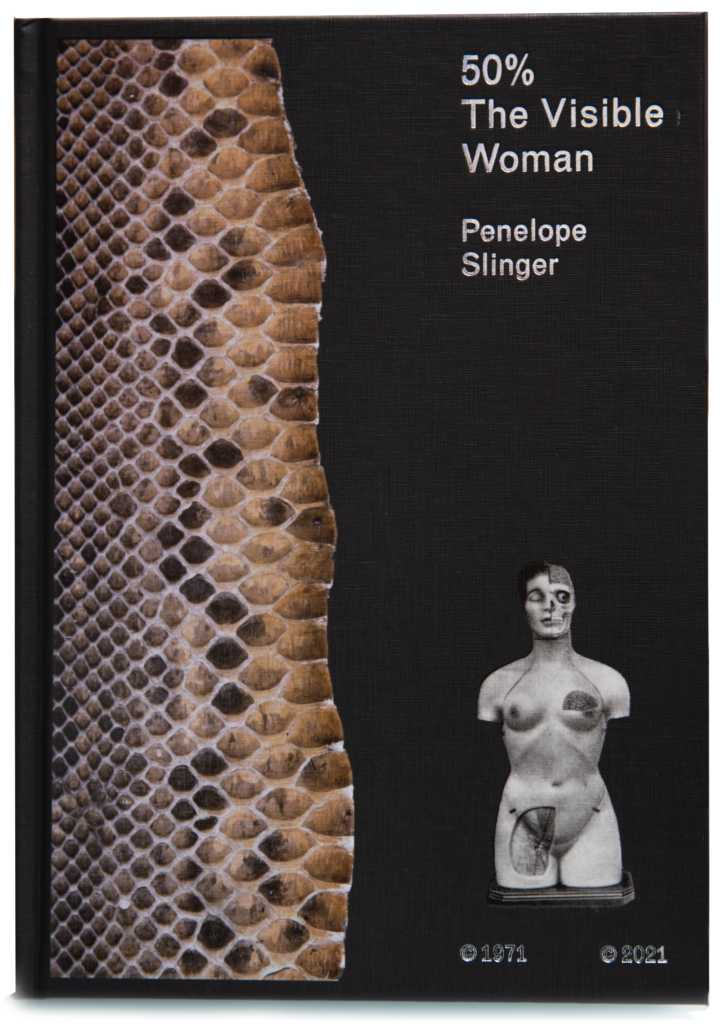

“I sit at the shrine of mystery and worship,” Penny Slinger tells me. 50% The Visible Woman, reprinted (by Blum & Poe) 50 years after she presented it covered in snakeskin as her college thesis, could say the same. The book is a precious object. Photographic collages overlaid with translucent sheets of poetry call to mind the old anatomy books she loved as a child. The images are beautiful and shocking.

What did we talk about? Poetry as an element of collage; the self as muse; the mythic feminine; ornamentation; the body, exterior and interior; and her thirty years of living and working as an artist—in New York, the Caribbean, and California—between her decisions to leave the fine-art world and to return, in 2009, with the exhibits Angels of Anarchy and The Dark Monarch. When I first discovered Penny Slinger, I went searching for her books. Now, finally holding 50% The Visible Woman in my hands, I hope I can soon fill my shelves with the rest.

Lori Green: Congratulations on this new edition of 50% The Visible Woman. It’s beautiful.

Penny Slinger: I hand-held every single aspect, trying to get it just right. This edition combined the handmade one I did as my thesis at Chelsea College of Art and the one that was published. So it’s an ultimate ‘best of’ volume of the two versions.

Do you still have any of those three originals with the snakeskin covers?

I do have one. Mine isn’t in very good shape. The Edinburgh Museum Library has one from the Penrose collection, in perfect condition. So I don’t know what mine went through. It’s a little rough, but I’ve got it.

I was thinking about what you’ve said before about living your life as a work of art, and the inverse of that: the art living its own life. I see parallels between you, yourself, and 50% The Visible Woman. At the time you published it you were making art in the public eye; some years later you left the fine-art world. This book also started its life publicly, before retreating into its own privacy. Now, just as you have returned to the fine-art world, the book has as well. Do you connect with the idea of 50% The Visible Woman—and all art—living its own private life?

Well, when I left the fine-art world, I didn’t really go into a private situation, although it’s been perceived as such. I was trying to find ways to get the work out there outside of the elitist—and what I found rather limiting—structures of the fine-art world. I thought that my work would be indelibly printed in the history books of art. And yet I found, to my surprise, oh, it’s been out of sight, out of mind. Because I wasn’t playing the game, it was almost as if I hadn’t existed. The fact that I was being lost and written out was quite upsetting to me. It was wrong. I always felt I was meant to be a significant contributor to both art and consciousness.

I made decisions in my life that were much more based on living my life than on careerism. Initially, when I “went away,” it was because I was interested in publishing. I thought, if I make books myself, this can get out to a much larger public. So I left England for America, in 1977/78, to work closely with the publisher who did Sexual Secrets, The Alchemy of Ecstasy, which ended up being a bestseller. It was translated into twenty-odd languages and did reach and touch a lot of people.

My partner at the time didn’t want to stay in America, and in 1980, we went to the Caribbean. We lived on Tortola, first, and then Anguilla, where I was out of the mainstream completely. But I was still working, every day, as an artist. I was a very big fish in a small pond. In my fifteen years there, I contributed a lot to the culture of the island. When I first arrived, I found that the people hardly knew there were Amerindians, the Arawak, living there before them. Reestablishing their visibility became my focus.

We have stages in our life. When we’re younger, trying to find ourselves, we’re rather self-obsessed. At a certain point, in our twenties or thirties, we begin looking more outside ourselves, which is often when people have babies. I didn’t take that route, but I did turn away from self-examination to examine cultural mores. In looking at the culture of indigenous people in Anguilla, I was really studying how to be with this planet and what we have lost touch with, what has been swept under the carpet of history. In the end, we are very much swept under the carpet ourselves.

I was completely involved in my life in the Caribbean. It was such a love affair with nature. But towards the end, I started thinking, “Hmm, maybe I am not meant to be off on a desert island.” Then life delivered. My relationship broke apart. It was like the stirrings happened in my consciousness and the next chapter opened. So I can say now, looking back, “Oh yes, it was always meant to be.”

I left the Caribbean and worked for many years, 1994 to 2017, in Northern California, with the younger creatives. I wanted to find out about this psychedelic community that I felt was very much on the cutting edge of consciousness and of art, this whole visionary-art movement. So I aligned myself with that. For a long time I thought that that was where I was going fit.

But after a number of years, I found that wasn’t the right fit for me either. A lot of the people I was working with didn’t know anything about me as an artist. I wasn’t promoting myself. I was supporting the arts, making videos and hosting multi-media events. I don’t regret any of it. I’m so pleased to have been able to examine and expand my own limits and knowledge. But coming back into the fine-art world was something I needed to do to fulfill my destiny as the kind of artist I always thought I was meant to be. I didn’t want to disappear. Then, again, things happened—I was in the exhibitions Angels of Anarchy and The Dark Monarch, both in England in 2009. That was my entry point back into the fine-art world. In 2017 I left Northern California, traveled for six months, and came to live in downtown LA in 2018.

As for 50% The Visible Woman, it had become a lost relic, even though at the time we put it out Rolling Stone wrote, “This will become as important on your bookshelf as Sgt Pepper is on your record rack.” Well that didn’t happen. It needed to be re-found because, as many people have noticed, the language I was using then is similar to the way a lot of people are working currently. It’s an important thread in the whole tapestry of pop culture.

I do wish that it had stayed around. Coming into my own, growing up, I would have wanted it on my bookshelf.

Right. And although it was challenging and costly to make this new edition, to do it in the way I did the first book, with the translucent pages of poetry interleaving and all those bells and whistles, I wanted to make it accessible, especially for younger women. They are the main audience who follow me on Instagram. Hopefully it will be something that people across the board can actually afford and get into their lives.

Speaking of Instagram, these days most people will first see these images online, without the context of the book and its poetry.

Well, images should stand on their own, in a language that’s communicable and direct and has its own energy. My complaint about social media is the lack of attribution. You’ll see an image without acknowledgment of the artist. The artist and the viewer deserve that information. A lot of people would want to explore further. Searching for the larger context and the rest of the artist’s work, that is where you discover the breadth and depth. Now, with digital media, the tools of making collage are so accessible. It’s become commonplace. On one hand, it’s lost its specialness, its rareness, its art-practice element. These days anyone can make something beautiful, shocking—but it can just be eye candy. What is important is the artist’s practice, what these images arose from, the context. There needs to be the ability to see what this grew out of, where you can go, “Aha! Now I get it.”

As for seeing the images without the poetry, I’ve never wanted to explain away my imagery with words, where the viewer can say, “Oh, well, now that’s what that is.” No. I wanted to complement the art in a way which opens more doors into perception, allow people to bring their own consciousness to it. The poetry should be as evocative and paradoxical as the imagery.

With the way the poetry is printed on that translucent paper and laid over the images, the collage never obscures the poetry. And yet the poetry softens the collage, until you lift the page. In the interview with Linder Sterling at the back of the book, you called the poems a veil. There’s so much in the book with ornamentation, decoration, clothing. There’s removed clothing, the snake with its snakeskin, the sarcophagus, all of these different forms of the veil and its removal, what is underneath, the undressing, and the way that the ornamentation is a part of us. Whatever is underneath the ornamentation, is it truer when unveiled and naked? Or is it naked and lacking?

Hopefully both the poetry and the collage speak the naked truth. I’ve always worked with words as well as imagery. Words fall into my head, much as visions appear in my mind sky. The overlay consolidates that connection—these are not two separate entities. Collage is a dancing of elements, until a frozen moment. That’s the way I felt about the words, too. The poems have a very visual aspect—they dance and play alongside the imagery. This whole thing was in a grander dance.

They’re all veils, every layer, as if you could see it in three dimensions, going back into infinity. I’ve always been interested in the poetic voice rather than the linear narrative voice or the descriptive voice. I wanted my words to be disjointed, or as free associated as the imagery. That was the idea of 50% The Visible Woman. You only see part of what’s going on inside. The words are just another layer, which can help you to somehow navigate and exhume the mysteries that are indefinable, ineffable.

Because we approach those mysteries with words, I wanted to use them in conjunction with the images, in a way I hadn’t seen done before, but which showed that they’re associating and both layering, one upon another, in the complexity of the feminine psyche—I felt that what’s inside the woman was an untraveled realm in the art world. We’ve been so fascinated with the surfaces for so long, and with the ornamentation, decoration. Of course what we wear does have significance. The Arawak Indians for example, unless they had their one little waist band with an ornament, they felt very naked. It was totemic; it had meaning as a glyph. It’s magical rather than just decorative. Our adornments are not just for vanity, but for resonance—they transmit something to someone who sees you. It’s not just to look pretty; it’s a language.

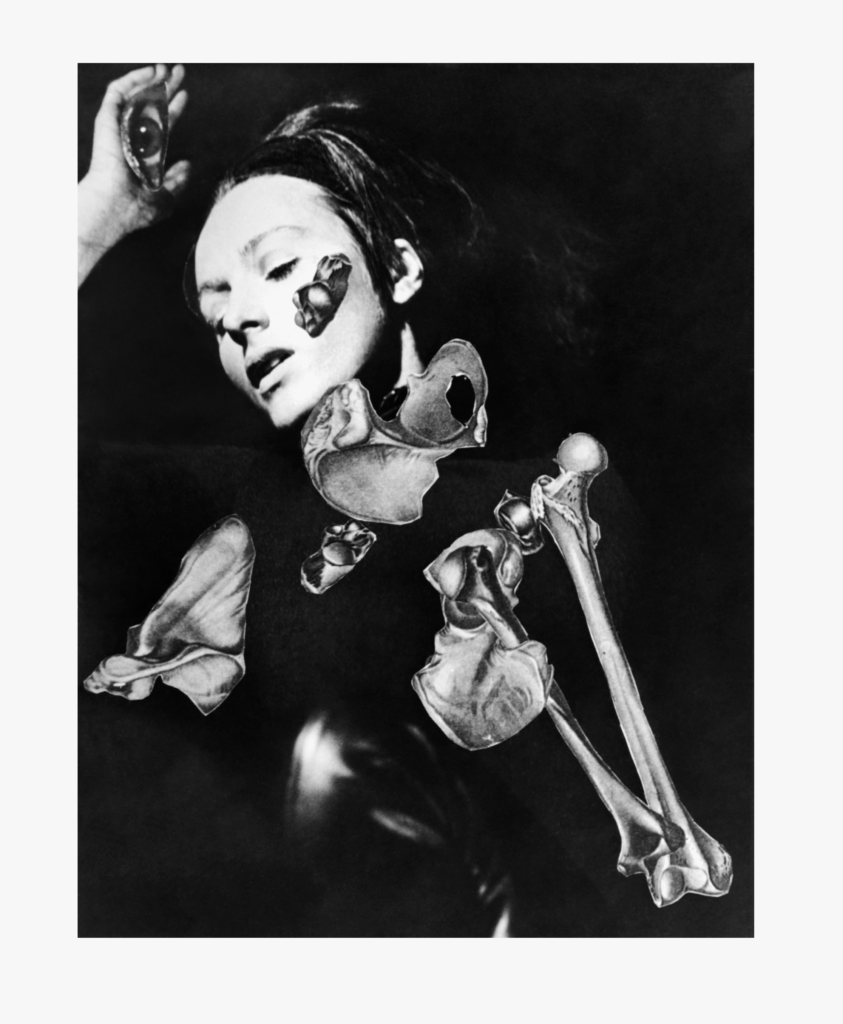

And you’ve traveled down past ornamentation to internal body parts, with the medical images in the collages. How do you feel you examined the feminine psyche by going deeper, in this almost brutal way, moving from the obviously beautiful to what is more difficult to see as beautiful?

I’ve always been interested in what we see as beauty. One of my favorite things as a child was looking at those old-style anatomical books with transparent layers; you’re seeing one body system under another. Of course there is beauty there—we’re all like this under our skin, no matter what features we have. I was also squeamish about the body’s inner workings, and that’s why I went and took photographs and drew in a dissection room at Guy’s hospital, to overcome that squeamishness. I think all of us need to acknowledge that we are spirit in flesh, to candidly seeing what this flesh is.

I found these anatomical images to be a good metaphor. When I would peel these layers away, revealing inner worlds, it was symbolic as well as literal. You could suddenly come into the universe within, through our human, flesh-and-blood reality. And I like the shock value. It was easier to get people’s attention when you could present them with something a little shocking alongside the beautiful. If you put the two in the same bag and shake it up, you have a chance of shaking up people’s psyches too.

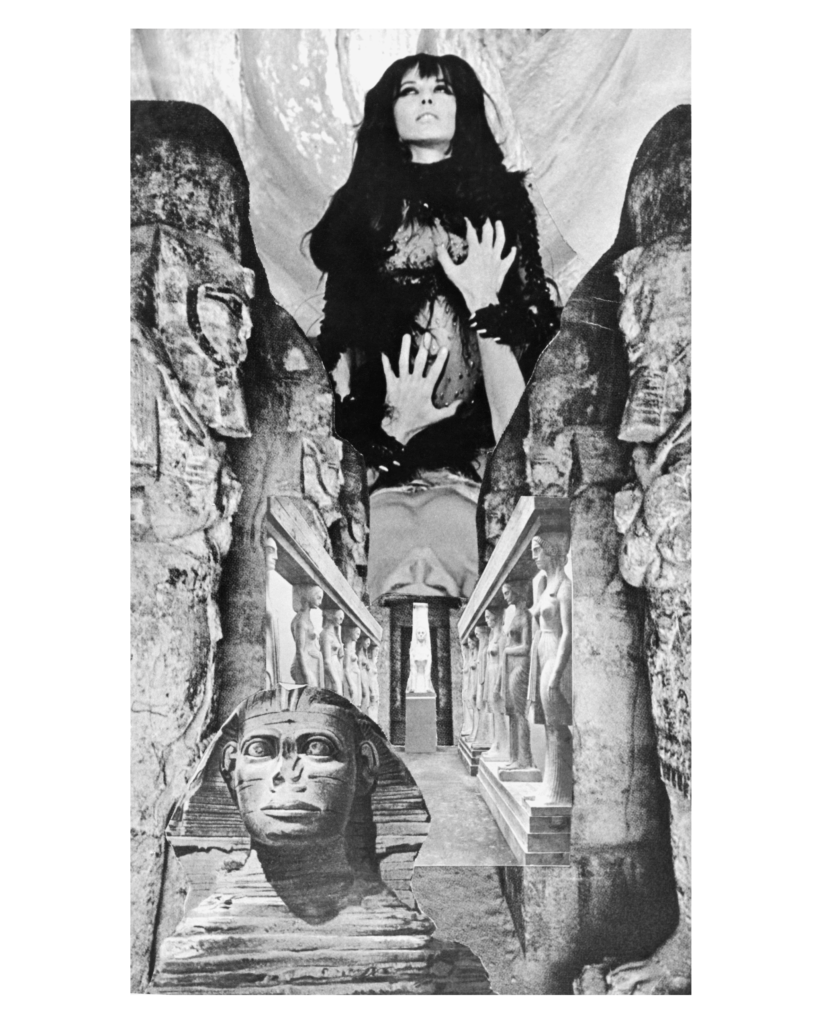

I had always thought that collage was what I did as a child, where I’d create mountains or other entities from bits of colored paper. I thought that you were meant to see where the pieces stuck together. Then I saw the collage books of Max Ernst—that was my aha moment—and Une Seamline De Bonte came into my hands. He created worlds from old engravings; you couldn’t see where anything was stuck together. It became a new space, a seamless reality. This, to me, was magic. You bring what does not usually meet, in the real world, together in this dream world, this fantasy, mythological world.

You have said that collage means taking two pieces of reality and making a new reality. It’s a kind of magic. Did you feel that, with 50% The Visible Woman, you had a particular reality to create, and collage was the only way?

So I fell in love with collage as a tool. I began, not to copy and emulate what Max Ernst was doing, but use his example to do what I wanted to do, which was to explore the feminine psyche and our inner workings, which include dreams and fantasies, archetypal realms and mythological realms, but from a woman’s point of view. I was grabbing and making things from this lovely raw material, including myself. You can be much more ruthless with your own image. Because it’s yours, you can do with it as you want. Luckily, I was an attractive young woman, which has its own magnetism. I could use that, disrupt it by recreating who I was, by turning it outside in and inside out. Although there were female surrealists, I hadn’t really seen this tackled before. I’d seen women used as the male artist’s muse. I wanted to see myself through my own eyes, to use myself as muse. Now it’s super topical. But back then it was a virgin territory.

You see all of these beautiful women photographed by the surrealists, Lee Miller for example, whom you’ve spoken about having a relationship with, then look into them and realize that most were brilliant in their own right. When you were starting to make your own art in the vein of surrealism, did you feel a connection not just to Woman universally, but to those specific women?

Not particularly. It was Max Ernst’s work, his language, that shone so brightly for me—and specifically his collage books, although I did also appreciate the Europe After the Rain series very much. With someone like Leonor Fini, I was not initially attracted to her work; her more fey style had less substance to me. However I saw an exhibition in New York, a few years ago, and felt like I really met her. It was a wonderfully curated exhibition with video, sound bites, context, so much of her that I hadn’t known about before. That established a real connection. But that was many years later.

People have said, about Ernst, well, what did you feel about the sexism? But I didn’t think of his work like that. He wasn’t fixed as this male figure. It was mutable for me, a magical figure moving through fantastic worlds, the archetypal dream world—the way he morphed into his alter ego, the birdman Loplop. And the female figures in his work were different versions of the anima. They were very much soul images.

I loved other photographers like Bill Brandt, Lucien Clergue, the way they use the female body in water and as monumental forms in a landscape. Of course I saw Man Ray’s work, with Lee Miller as his muse—so very beautiful. And Lee again, in Cocteau, a statue coming to life—so magical and transformative. But even Frida Kahlo, I didn’t really know at that time. As I was doing a series of bath reflections, looking down at my own body in the bath, I found What the Water Gave Me in an art book, copied it, and put it in my sketchbook. But really discovering her came later.

Do you do you feel that the recent increased awareness and attention to your work was inevitable, that there was some kind of gravity and your work was always going to return?

Well, it’s still a work in progress. There are a lot of bodies of work I’ve been doing, over the last few years, that I have not yet had an opportunity to exhibit. I like to feel that it is inevitable that people will put all the pieces of my oeuvre together, even if it’s after I’m gone. But it would be so much better if it happened while I’m around, because I’ve got the best bird’s eye view of it all.

My practice now is very much connected with what I believe is the next stage of feminism, which is ageism. I’m finding that the wisdom of experience, which is what we as wise women have, is not really percolating back into society and into culture, because we’re no longer the young, hot, magnetic women. We tend to get marginalized and become invisible. That’s why I’m using my body again now, at the age 70-odd, as my muse, presenting myself naked as the vehicle.

I’m still waiting for all of this work to be shown. I had my pandemic series of My Body in a Box presented as part of my last exhibition. So that’s good. But I have four other major bodies of work that haven’t really been seen. My dream is to have a big exhibition with all these different rooms for the different parts of my artistic output. At first glance they may look disconnected. But when you see them all together, they connect the trajectory of my life and art—the dots join together to reveal the grand design.

I don’t know many people who have such a scope in their oeuvre. If I’d stayed on a narrow path and continued to do more of the same, I would probably be much more successful in the art world now, but I wouldn’t have the same range of experience, the same richness of life. Working on An Exorcism, I was exploring my psychology and the culture I came out of; then I went on to explore tantra, looking at the divine feminine, asking what is the next stage of the evolution of self, once you’ve processed your psychology; then I looked, as I said, at indigenous culture. So there are many pieces that form a greater whole. I hope I get to present them.

I hope so too. A body of work is so much richer for exploring new ways of looking and even just new tastes.

But it makes it harder for people to put you in a box. And if you can’t be put in the box, you’re a wildcard. I remember speaking to some of the successful pop artists who were teaching me back at Chelsea, people like Allen Jones. I was told it’s great to be successful and have a gallery—the problem is they’ll want you to keep doing more of the same. I understood, early on, that that’s one of the traps. You are forced into this straitjacket, rather than being free to expand and do what you need to do, which could be irrelevant to the commercial demands of a gallery.

Your interest in Egyptian myth especially, in 50% The Visible Woman, has that been a constant in your life and work?

Absolutely. Other cultures and other times have always been fascinating for me. When I was at school, when we came to Egypt, it felt totally familiar to me. They had such a wonderful, sticky weave between the life we’re living and the afterlife and the mythology of the interface. Looking at Joseph Campbell and the idea of the hero/heroine’s journey, I’ve always felt that living a life that’s larger than the mundane life, actually finding your mythological journey, is necessary to living outside the box and fulfilling your potential as a magical, multidimensional being. I’ve always been fascinated with that. As I studied Tantra and looked at all the richness of the Indian mythology—everything I did before creating the 64 Dakini Oracle, which I’ve been hoping to get published for a long time—that was so fascinating for me too. The visual language of the mythological has always been deeply embedded in how I see things.

How confessional is the “I” of the poetry? Is your use of your poetic voice, as an element in the collages, similar to that of your photographed self? And has your connection to that “I” changed in the last 50 years?

I was speaking as myself, but I have never drawn any lines, made any distinction, between who I am and my mythological persona. It’s all me. I have always tried to close the gap between my life and my art and make it all my living art. Yes, I use first person sometimes in the writing, much as I use photos of myself, but I don’t do it all the time, much as I am not featured in all the collages. It’s a blend, a mix, free flowing, and I allowed it to come through in whichever form it did.

I have expressed myself in a variety of ways during the course of my life. It’s ever-evolving. But it is still the same being at the heart and core of it all. Although the ‘I’ I am now may have shifted and developed over time, the same music still flows through me, and I recognize it as my own.

I know that you said that in writing, you’re more interested in the image than the narrative.

I like to let things come into my head in a free way. So the poetry was written like that. I like to think of it as the written equivalent of collage. You don’t have to obey the rules of linear narrative. I have enjoyed the use of a very dada and surreal approach to how I put my thoughts together. Even now, I enjoy it most when I don’t have to edit it, when I can let it be itself and have its own music. In my third book, Mountain Ecstasy, I wrote the poetry, but in conjunction with my partner, Nick Douglas. When I write something, it has its own rhythm, its own vibrational field. When something else or someone else comes into it, when it doesn’t flow how I heard it flow, I feel, “Oh, that’s not quite my music.”

I did want to say, I hope An Exorcism is reprinted.

Yes, I hope so, too. That’s the next thing. I did make a film called An Exorcism – The Works a few years ago. It hasn’t been released as such yet. The published book only has 99 images, but there are closer to 200. The film shows all of the images. I deconstructed the collages—you’ve got the empty room and the elements, and we go through it like 3D postcards. We created music. I speak the titles of each piece, then at the end I have a transmission, summing it all up. My partner, Dhiren Dasu, made the animations. We created music with David Kobza.

Is there anything else about the book that you want to share?

It’s vast. If we’re focusing in on the book, the whole approach about the dialogue between looking in and looking out, seeing how one is perceived as a woman and the cultural stereotypes which were projected onto the female gender. Things have changed quite a lot now, but at that time it was pretty stiff. You had advertising and fashion models over one side and pornography on the other. It wasn’t something that a nice girl would do, to show herself naked in any kind of media. But I wanted to break open those paradigms. It’s why I put myself in men’s magazines. People could first be attracted to me, but when they read my words, they’d have to reexamine that objectification and find that I was very much a subject.

I was not quite in line with a lot of the feminist movement at the time. It was rather heavily intellectual and militant; the sensuality and sexuality were being left out of the picture. There was finger pointing at someone like myself who was showing her body. But I felt that it was so important that we claim the right to have our own sexual presence and our sensuality be part of the equality, not to be undermined or diminished because of that. I felt that we had been shortchanged. I wanted to reclaim our right to have pleasure. We suddenly had freedoms we hadn’t had before. The pill was liberating for women, yes, but it was also liberating for men. There was a different kind of dialogue, of equality, of openness, of the forefront of gender fluidity. Men could begin to express the feminine side of their nature.

I do feel that we’re all—creative beings in particular—androgynous.Within the creative act is a marriage between the male and female. Then “the child” is born as a work of art. I was trying to have that frisson, that dynamic presented in the work. Both sides of our nature are terribly important in this liberation of the feminine, and in terms of our relationship to the planet. The dominating and power-over approach has been detrimental to humanity and to nature. We need the feminine side of collaboration and cooperation and symbiotic support for our whole systems. Men need to wake up to their feminine side as much as the women need to be empowered. That is what will allow us to have longevity.

This post may contain affiliate links.