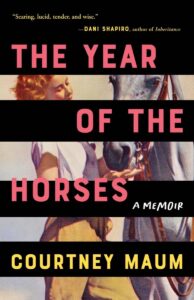

Photo by Kenzie Odegaard Fields

Courtney Maum’s The Year of the Horses [Tin House] is, first and foremost, about reclaiming joy. Written in beautifully expressive prose, Maum’s memoir concerns her journey with depression and the turbulence of early motherhood, and how returning to her childhood passion of horseback riding allows her to feel free again. At times brutally honest as she interrogates how she came to this place in her life, her book is never less than revelatory, and I was thrilled to talk to her over email about the art of the memoir, the legacy of horses in fiction, and the politics of the body in her work.

At what point did you realize your experiences of these past few years would coalesce into a memoir? How early on did you decide the major through line of the narrative would be horses?

The seed was planted in 2017 when I wrote an essay for the (now defunct) “Sporting” section of The New York Times about trying to learn polo as an almost forty-year-old. The essay explored how I was desperate to do something outside of my identities as mother, wife, and writer, and I got a lot of email from people whom the piece inspired. I started thinking that there might be something interesting about my pursuit of something that I wasn’t particularly great at. The fact that I was doing this crazy thing just because it made me happy was a novel act for me, especially in a culture that wants us to be a blue-check verified expert at everything we do.

I know you are a big advocate for demystifying the publishing industry, and specifically the art of writing a book proposal. Did you find the process of pitching a memoir substantially different from pitching a novel?

I didn’t sell this book on proposal, I sold it based on a rickety first draft. I don’t think it would have sold if my editor, Masie Cochran, hadn’t also done my third novel and thus knew what I was capable of accomplishing in revision. What was hugely different about the memoir process was that I elected to share the memoir early on with the people who are in it. That was frightening for me. I’m not someone who has a lot of readers. My readers are my husband and my agent—it’s been that way since I started publishing. But I didn’t want to hit the proverbial pavement for this book if my own “characters” were angry or resentful or just felt taken by surprise. So that early sharing was an uncomfortable—but necessary—part of my process.

Did you look to any memoirs for influence?

I did, in the beginning, but pretty much every book that I picked up for guidance I put down pretty quickly, realizing I needed to figure out how to get the story right, myself. What ended up being the most influential tool for me was Dani Shapiro’s “Family Secrets” podcast. I learned heaps about the structure of secret-keeping and sadness and release and what that timeline looks like from listening obsessively to every episode of her show. The generosity and courage of her guests really inspired me to dig deeper into my own truths.

Something that works beautifully in this book is the way you thread passages of memory through the present narrative. How did the structure of the book come together for you? Was this an organic way of remembering?

The structure came to me like a lightening bolt one day. My editor has just acquired the manuscript, and we were discussing how to fix my messy first draft on the phone. Masie asked me when the first time I saw a horse was. It’s not a question I’d thought of up until that point, and it jogged a memory: that my first horse had been this mahogany rocking horse that my mother got me for Christmas that turned out to be too heavy to rock. That was the first of many intelligent questions on Masie’s part that just opened up the book for me. When I got off the phone with her, I storyboarded all the chapters out on these huge sheets of paper in pretty much the same order (and with the same chapter titles) that the book is published as today. I had the story inside of me, I just needed the right editor to get that story out.

Relatedly, how much did you allow yourself to trust your memories as you were writing this? Did you try to verify certain events with your family or did you rely on your own recollections? What do you think a memoirist’s responsibility is in this area, if any?

That ended up being the silver lining of sharing the material early with my family—I remembered some things wrong! In the book, I share those mistakes and point out what I misjudged, which underscores my journey of self-discovery and forgiveness. As a child, I made the wrong assumptions about some things and as an adult, you see me realize this. I really liked sharing my mistakes in this way and hope it will encourage others to own their mistakes, their guilt, some of the things that they are ashamed of. Though I felt personally called to share my material with people in the book before the book came out, that move won’t be right for everyone. Sometimes there will be circumstances that will keep such early sharing from being a good or safe idea. I don’t think there is a blanket answer when it comes to a memoirist’s responsibility—every individual’s responsibility will depend on their book’s content and its context.

I admire that you are rigorous with self-interrogation in this story. It often reads as though you are discovering your own flaws and desires as you write in real time. How far did you push yourself to be honest and even self-critical at times? Is self-revelation something that is essential to your writing, even in fiction?

I pushed myself quite far! Emotional excavation work is deeply important to me. I spend a lot of time with each sentence asking myself: is this as true as it can be? Am I taking a risk here? In memoir, when a writer is being courageous, it’s electric and exciting. I like to feel that in what I read, and I strive for that same feeling when I write.

Thank you for bringing up the death of Artax in The NeverEnding Story, which was also traumatizing to me as a young horse girl. The horse stories I consumed as a child were almost all deeply intertwined with trauma and loss. I’m thinking Black Beauty, The Black Stallion, The Horse Whisperer, The Red Pony, etc. How do you think the “precarious and dangerous and full and so unique” union between horses and humans, as you put it, informs this tradition?

Well, I think a lot of it comes from the inherent danger involved in any equestrian sport, even on the ground. Many of the worst accidents I’ve heard of involved people who weren’t mounted, they were just in a barn, and something wild happened. We know that we are taking a risk when we get involved with horses, but we do it any way. Most of the people I know keep doing it even after they get hurt. Why? I can only answer for myself, but horses offer me a portal to a place where my mind is focused and calm and utterly content. There is nothing else there. No room for other worries. That place is paradise for me.

You quote from Centered Riding by Sally Swift, a book I love and that helped me immensely with my own riding. It made me think about how in horseback riding, the body is allowed to move intuitively and freely. You write strikingly about the way your body is controlled and disrespected through instances of your eating disorder and your medical care after your miscarriage. Can you speak on the intersecting body politics in your book?

Gosh that is such a great and complicated question. I don’t know that I ride intuitively nor freely yet—that remains a goal. Currently, I have to counteract a lot of bad habits that I have, like slumping my shoulders, turning my toes out instead of in, and forgetting to breathe from nerves. I think the thing about horses for me is that they are intuitive and free in their bodies. Even though they are nervous creatures by nature, they’re still extremely physical. They’re big, they are heavy, but they’re fragile, too. Though some people manage it, it’s hard to not see a horse you care about. If they are losing too much weight, you see it. Not eating, you see it. Through most of my memoir, my principal injury was that I wasn’t seen. The tension between visibility and invisibility informs a lot of the material.

On the flip side, horseback riding is not free of class politics. There are so many economic barriers set up that keep the sport predominantly for the wealthy, including cost of training, cost of equipment, and even ease of access. There are some modern efforts to combat this, such as IEA teams, but it’s still a complicated sport to love. How much did you consider bringing this into the narrative?

In the book, I explore how I avoided a return to horses because I was convinced I wouldn’t be able to afford it. (My father paid for my riding when I was a child.) In order to ride as an adult on a freelance writer’s salary, I went to places that allowed me to work against the cost of lessons, took group lessons instead of private lessons, used personal relationships to find an affordable horse lease, but ultimately, it’s still my privilege and education that got me to any of those barns in the first place. In the book, I get involved in polo where the class volume is turned up to the max. I explore that classicism (and racism) in later polo chapters, but I didn’t want to paint the horse world as a kind of hellscape because I have met a lot of people who are actively trying to bring more diversity and accessibility to horse sports. For the time being, I think it is a question of exposure and networking. We need people to expose underrepresented groups to horses, and we need people in place to allow such underrepresented parties to continue riding if it’s something they get into. Change is not going to happen overnight, but I do think it’s underway.

I have always been curious as to how authors approach ending their memoirs. You can’t force the “plot” in a certain direction as you do in fiction, you can only dictate the final tone and imagery. How did you decide to end the story where you did, by focusing on your daughter Nina and her own blossoming love of horses?

Well, Nina gave me the book’s ending! I was in a parent/teacher conference when the teacher told me Nina was writing a nonfiction story about horses. When I got the little book home and I read it, I just knew: there was my ending!

The Year of the Horses

The Year of the Horses

Courtney Maum

May 2022

Tin House Books

Emily Saso is a writer based in New York City. Her work has appeared in Bellevue Literary Review, LitMag, and Harpur Palete. She was the recipient of a New York State Summer Writers Institute Merit Scholarship. She currently works at Columbia University in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

This post may contain affiliate links.