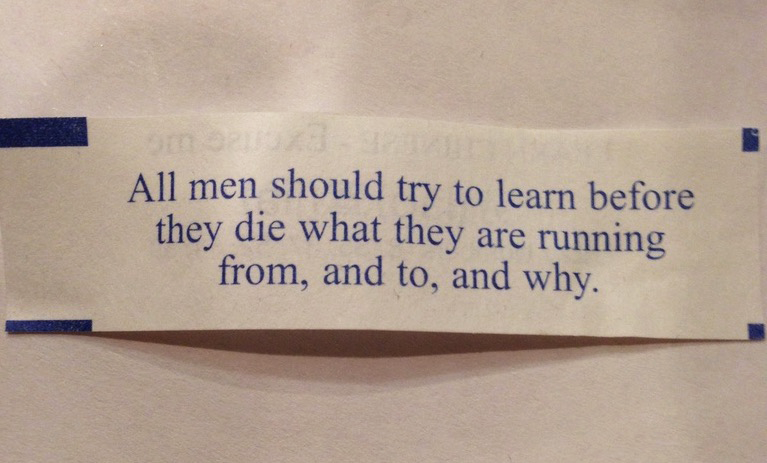

Rebecca van Laer’s How to Adjust to the Dark enthralled me from the first couplet, which is basically the first line of the hybrid novella:

All men should try to learn before they die

what they are running from and to and why.

The book blends criticism and poetry and narrative fiction to explore the ruins of an ex-poet’s poetic identity. Close readings of her own poems are laced throughout the ex-poet Charlotte’s story, informed both by her recollections and the poets who have led her to, through, and away from poetry. In some ways, How to Adjust is a formal-adjacent education in poetry, a graduate seminar of stitched together syllabi from half-skipped classes. But van Laer renders the failed dream of romance in such explicit and exposed arcs that whatever I learned about poetry seeped in through freshly-opened wounds.

I wrote to her as soon as I finished reading. “Can I interview you?” I asked. We decided to spend a month writing to each other. I think we could have spent a year.

Friday, Feb. 18

Dear Rebecca,

Have you had Covid yet? I had it last week. Every day was a new symptom: strep throat to sinus infection to tooth ache to migraine. Throughout, brain fog and the boredom of isolation persisted. I couldn’t focus to read a book, I couldn’t bring myself to type a page, I could barely pay attention to the cartoons on my computer screen. On day six, I received a copy of How to Adjust to the Dark, like a harbinger of good news. By day seven, I had to get out of the house. I double-masked, leashed the dog, and brought your book and a blanket on a long walk to the park. It was Super Bowl Sunday. Not too many people were out.

My brain was still foggy, but I found that I couldn’t stop reading your book. I read the entire thing that afternoon, with my dog’s leash slipped around my ankle so she wouldn’t wander off. At first I was captivated by the concept of a poet close-reading her own work, like an archeology of the self. Each chapter reads like a personal essay that is simultaneously entwined with the subject and at a complete remove. Outside sources come up—Auden, Barthes, Carson, Foucault—but the primary source used to analyze the work at hand, the poet’s own experience, is one which the readers will never have full access to.

And of course, this is fiction. So while at first I was in it for the theory, the poetic analysis, I quickly became wrapped up in the narrator Charlotte’s story. I saw myself in her, as I’m sure many poets who are familiar with romantic obsession will. What is it about this kind of toxic romance that Charlotte finds herself in, over and over, that is so poetically generative?

When I think of poetry in the context of this kind of romantic desperation, I inevitably think of magic. At times of romantic turmoil (painful in a way that reminds me I’m alive and makes me excited, somehow) I’ve written poems thinking I’m documenting my feelings, my observations of a moment. Then these poems get stuck in my head. I reread them, I repeat them. And eventually, they “come true”; something happens to prove to me that I wasn’t writing about the present when I wrote about them, I was writing about the future. Poetry as premonition? But if I hadn’t written them, would life have happened like that? Poetry as incantation.

By the end of the novel, Charlotte has “made and unmade myself through the medium of verse” and abandoned poetry, finding stable love that doesn’t create the intoxicating gap into which desire can pour like her previous relationships did. “I wanted to destroy everything that made those poems possible. Everything I was taught about what it means to be a writer, an artist, a woman. Everything I was told about what it means to be traumatized, and depressed, and diagnosed. None of these beliefs made me happy—they just made poems.”

I think the book ends on a note of hope for those of us who tend to mine our romantic dalliances for artistic inspiration. There’s premonition and there’s incantation, but there is also something that is perhaps more pure: invocation. Charlotte ends her self-dig with a series of questions about what else is out there, “what else is possible” beyond desire. And the key to invocation, which ultimately is prayer: “to ask for help in answering it.”

I’ve become bored of my romantic obsessions lately, instead wanting to dig into why I always find myself writing about them. For Charlotte, that study seems necessary in order to move past it and write the bigger picture. I’m hoping I can learn from her and just move past them, for now, finding what else is out there without spending any more time in the intoxicating gap. (My new year’s resolution was to stay off the dating apps for the entire year, and I’ve stuck to it so far!)

In your bio you sometimes describe yourself as an “ex-poet,” so I have to ask: how much of you is in Charlotte? Did you give up poetry for the same reasons she did?

H

Saturday, Feb. 19

Dear Hannah,

I’m glad to hear you’re on the other side of COVID, and what an honor that my book arrived at a sort of gateway moment. It’s so strange to imagine another person reading the book in the park, and so lovely!

I’ve been lucky—I still haven’t gotten COVID. I have the advantage of living in Upstate New York and working remotely. But I remember the heaviness, long-lasting feeling of fuzziness, and disconnection from self from my last flu so well. Charlotte has an experience like that in the book, which is based on a real-life illness of mine. It’s such a relief to feel clear again!

To start with your last question, there is a lot of me in Charlotte—the story begins with my own poems. I began the project of integrating them into a prose narrative in 2015 and did a big revision last year, so I’ve been moving further and further away from the version of myself she is based on. In the process, it became clear that although life does not have a clear narrative arc, this book needed one. While I stopped writing poetry for reasons related to Charlotte’s, the reality was more complex and more gradual.

During the first few years of my PhD program, I was still moving quickly between various objects of romantic and platonic obsession. I continued to write poems about them out of a feeling of obligation. I called myself a poet; the identity this shard of information provided seemed at once whimsical and serious, and this was precisely how I wanted others to see me. So of course I had to write poems!

But my relationship to the medium had changed. I was taking classes that centered on theories of the lyric; this became a topic of my field exams and eventually a central part of my dissertation proposal. And I was not exactly thriving in graduate school. Years before, writing had come easily and felt necessary—my feelings built up like steam in a tea kettle, and poems were the whistle. Now, my relationship to poetry felt distant and analytic. Writing was a source of pressure rather than relief. I was struggling quite a bit with anxiety; I wanted nothing more than relief. So the stream of poems trickled off. Yet to call myself an “ex-poet” became (and is still) a way to hold onto a part of what poetry had meant to me. It was easier to define myself through negation than to figure out what the positive might be.

Eventually, I realized that I could not create scholarship or creative work out of a sense of obligation to a set of interests I had adopted as a teenager. And that meant that I had to try something else. Writing is hard and solitary and often thankless—so if it does not grant the writer a feeling of excitement and discovery, what is the point? That led me to change my dissertation topic, and eventually to start writing How to Adjust to the Dark.

I relate to so much of what you say about poetry as magic. For me, too, my own poems had been incantations that I could read and recite to be in touch with myself while also receiving a kind of exposure therapy that made chaotic emotions more manageable. So perhaps it is not a coincidence that the original ending to the book was a long section on tarot as Charlotte’s new tool for self-understanding—following your thinking, a shift from one form of magic and premonition to another. I’ve been trying to write about why that felt wrong to me, and although I haven’t fully figured it out, I do think ending on a series of questions was important, if nothing else to express that my own understanding of identity and art and love is always shifting.

That is another place where Charlotte and I differ; her story crystallizes a particular feeling of hope and expansiveness that I had during the strange year I lived in New Orleans (2016-17). That state of mind feels so far away now, but I am glad that I can return to it through her.

I’m so curious to know what directions your own writing has been moving in since you app hiatus! My best friend always jokes about the time she recommended a novel and I asked “Is there dating in it?” To this day, I know this question plays an outsized role in the choices I make as a reader and writer, and I’m not sure I’ll ever fully understand why.

rvl

Wednesday, Feb. 23

Dear Rebecca,

Since I stopped dating, I’ve mostly stopped writing poetry. My poetry is often self-reflective rather than externally observant, and I wonder if that’s how I’ve dated, too. It’s likely that my priorities have shifted from dating and poetry at the same time for intertwining reasons rather than because the two are necessarily intertwined. But it still makes me wonder, do I just use dating as a way to see myself better, a way to experiment with my ego? And if I have to be dating to write poetry, can I really call myself a poet?

How to Adjust to the Dark is sort of asking this question, too. At least, it’s asking questions about identity and what one calls oneself— specifically about when one calls oneself a poet or a writer.

One thing I’ve been thinking about language lately is the necessity to name something in order to know it. If we don’t have the words for betrayal or broken promises, can we know when we’ve been betrayed? We know something bad has been done to us, but what? And similarly, if we call ourselves a poet, are we more likely to behave in a way that we believe is poetic, even if we aren’t actually writing poetry?

In the same chapter where Charlotte recounts her flu, she analyzes “Like a Doll” which is a poem sequence that pulls from her childhood memories, particularly of porcelain dolls. This is the first chapter where I really noticed her name, because you make a point of it. Charlotte named all of her dolls after herself. While this might be read as narcissism by some, Charlotte says she named the dolls after herself because she saw herself reflected in them, “pleading, silent.” I think again of the incantatory power of poetry when I think about naming; did she make herself pleading and silent by identifying herself with the dolls?

Another thing I noticed about names in your book is that none of the exes have them. Charlotte has a name, and her friends have a name, and her present-day partner has a name. But the men from her past are called things like “my ex,” and “the musician,” or just “him.” What does this say about their “realness” to Charlotte? Why did you choose to leave them un-named?

And maybe this would be a good time to ask about the name of the book. At the end of Charlotte’s story, she recounts the cycle of fear from PTSD. Her therapist tells her it’s hyper-vigilance. I think of the idea of being lit up, a body filled with flood lights and neon that won’t turn off. So while we often think of “the Dark” as something to fear, it can actually be a welcome relief, like silence after a false fire alarm. Reading the book gave me this new understanding of the title, but I wonder how you landed on that title (which is also the title of the last chapter, and the last poem Charlotte ever wrote) and how you imagined readers approaching and interpreting it before they read your book.

H

Tuesday, Mar. 1

Dear Hannah,

Yes, I think this book is at its center about these questions you ask: do I just use dating as a way to see myself better, a way to experiment with my ego? And if I have to be dating to write poetry, can I really call myself a poet?

To me, both answers are yes. Isn’t the self always most legible in relationship, whether to another person or to the words we begin putting on the page? Perhaps to be a poet or writer is simply to continue to think of writing as a medium for relating to self and to world no matter how long you go without doing it.

And I do think this fosters a certain kind of behavior, regardless of writing. I would define this as an impulse to seize onto moments of day-to-day life because they seem to have the seed of an artwork in them. (I’m reminded of a novel I cannot quite remember where a character is introduced as someone with an “artistic sensibility,” although they have not yet found their medium.) Whether or not these seeds grow into something (naming, understanding, becoming something else through the transformations enabled by language and art), they have been recognized.

Perhaps this gets to something about naming and not-naming of the characters: the transformations required to shape this narrative’s meaning. The lack of names for romantic interest draws attention not to their individuality, but to a pattern. It is my way of indicating to the reader that these relationships are, like you say, more a way for the narrative to explore Charlotte’s ego and its attachments as opposed to keeping any kind of fidelity to the complexity of each particular relationship or the other equally whole person who accounts for half of it.

The title has many meanings, some of which relate to the way it explores Charlotte’s attachments.

Before I began writing this book, I began calling and speaking it into being (the incantatory power of poetry, of words)—telling people I would write it, and mentally attaching this title to it. It does come from an essay mentioned in the book, Rei Terada’s “Looking at the Stars Forever” (which itself is an amazing title). I hope this does not sound like manifestation or vision boarding; I think my unconscious intention was to create a level of accountability with myself and with the world. (If you call yourself a poet, you must eventually write poetry. If you say you are writing a book, you must occasionally open up the titled Word document, even if you don’t do much with it.)

I was drawn to this borrowed title for a number of reasons. One of the books that helped me find my own medium again was Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be, and I also found her article on books for “secret self-help.” I was interested in writing something like that—something to help myself and others. This title has obvious association with personal “dark times” and specifically depression, something Charlotte is coming to terms with and that is not permanently gone or fixed at the end, even if she senses new possibilities for living with it. The darkness can also refer to the conditions of the larger world—in this novella, most notably the conditions of patriarchy, which of course are intertwined with the other oppressive hierarchies and flawed logics that make up the culture and that we all must live and make art within. (I utter the phrase dark times or dark days so often—language fails me. How else can we describe our world?)

Now, I think that the titular darkness refers also to the essential opacity of the self. I do not want my writing process to sound like manifestation because I know that the currents of feeling that shape our lives cannot be made fully logical and transparent, and therefore cannot be “corrected” in simplistic ways. While the book is full of self-analysis, it cannot arrive at holistic understanding or final thesis, but only questions. I am not sure this book helps, but if it does, I hope that it offers ideas for how to live with that knowledge—even understanding it as a form of relief.

Do you have any secret self-help books (or poems)?

rvl

Monday, Mar 7.

Rebecca,

Vision-boarding gets a bad rap, but I think it’s basically the same as accountability. When you make a vision board (or when you title a book and tell people you’re writing it), you’re making your intentions clear to yourself. It’s sort of like I said before; you can’t know a thing until you name it. And once you know it, you have some sort of obligation to it.

Then again, accountability is a much stronger force when there are multiple parties involved. I include the title and pitch line for my work-in-progress in many of my bios, because I need to know that evidence of my having started the thing is out there, documented and (god, I hope) seen by other people who might be interested in reading it one day.

This list from Sheila Heti is terrific (I actually thought of How Should a Person Be when you mentioned the character with “artistic sensibilities”—if it is not actually Sheila’s character in that book, the term is certainly applicable to her!). I especially like her bio: “Sheila Heti is the author of the” and it just ends there. Leaves so much room for shifting realities!

My personal secret self-help book, one I’ve recommended countless times to people I see myself in, is Melissa Broder’s half-fantasy novel The Pisces. It’s an erotic and hilarious and painful story about a woman who fights against the currents of romantic addiction and fantasy obsession. I also try to come back to Rumi’s poem The Guest House when I’m feeling antagonized by my emotions.

What are your secret (or not so secret) self-help books? (I’m sure we see some of them in your book, but do you have an extended list?)

H

Monday, Mar. 14

Hannah,

Maybe you’re right about vision boarding! Something has to be named to be known. But then what? I think that in the popular imagination, intention is enough, and then you can trust the universe to “match your vibration,” to bring things to you “with perfect timing.” But I’m not sure I trust the universe. I just looked up your bio: she’s working on a novel about a woman who inexplicably births a sheepdog. Is this still the project?! It sounds amazing, and perhaps related. The things we give birth to so often defy our imaginations or intentions with results that can be both beautiful and terrifying.

How Should a Person Be is definitely an important self-help book for me. I read it about three years before I started writing How to Adjust to the Dark, but I think it played a big role in helping me bring it into being.

And The Pisces is another big one, too, such an important rejection of the idea that love gives you identity, that being the object of desire is enough. The moment when Lucy asks Theo how many women he has trapped down in the ocean—and the answer is seventeen (!!!)—reveals something it took me a long time to understand—if you depend on someone else for your sense of self, let them extend it to you, you will never be able to enjoy and embrace your own singularity.

I love that Rumi poem. Thank you for sharing it. In graduate school, my professors were always encouraging us to memorize poetry to “have with us” in times of need. In the Desert by Stephen Crane is the only poem I still have memorized, which probably reveals something unflattering about my general relationship to self and world. Another poem that had an early and big effect on me is Lorca’s Romance Sonámbulo.

Lydia Davis’ short story “Kafka Cooks Dinner,” to me, is about living with despair and trying to make something beautiful out of it for the sake of oneself and others.

There are some theory texts that had a big impact on me and did not make it into the novella—Leo Bersani’s Is the Rectum a Grave, D.A. Miller’s Jane Austen, or, The Secret of Style.

Some other books that I consider self-help books—if primarily in the sense that you can emerge from them changed—include:

H.D., Tribute to Freud (which I originally wrote about at length in the novella—that all got cut)

Zora Neal Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God

D.H. Lawrence, The Rainbow

Richard Powers, The Overstory

And I would be remiss not to mention Rachel Cusk (who I talked about a little bit here) and Elena Ferrante.

Til next week,

rvl

Tuesday, Mar. 22

Rebecca,

Those poems! I’ve been wanting, recently, to write poems about the desert and the Southern High Plains as a place of wholeness. Both of these speak to me about that subject in very different ways. Thank you for sharing; thank you for the inspiration.

Yes, Wolf Baby is still the project. I feel like I’ve birthed it so many times, and so many times it has arrived as not the creature I was hoping it to be. And so I gestate again, and again go into labor, and again look upon my child with disdain. Sigh! You worked on How to Adjust in the Dark for over five years, and you’ve mentioned some of the ways it changed. Aside from the title, what are some pieces of it that you managed to carry through its development?

As the date of publication for this interview draws near, I suppose it’s time to wrap up my questions (though perhaps not our correspondence?). There are two I’d like to end with: 1) What are you reading lately? and 2) Are you working on anything new you’d like to share with the world?

Talk soon,

H

Wednesday, Mar. 23

Dear Hannah,

I’m so glad you liked the poems! I’ve never been to the desert at all, I don’t think, and I want to know and hear more about that—the sense of wholeness in the midst of the endless horizon.

While I worked on How to Adjust to the Dark for about five years, there were long, long gaps of not working on it. What I’ve found, unfortunately, is that it takes me about two years to gain enough distance to resolve narrative problems—or perhaps it’s that I’ve gained enough experience in life and as a person to understand what I wanted to say and how that can be rendered in the arc of a book. I have every confidence that you’ll get there (hopefully less than two years, but I think I’ve finally learned there’s no point in rushing things).

In How to Adjust to the Dark, the first three lines of the book were always the same; it was always the fortune cookie. And, actually, much of the first chapter has always been more-or-less in its current form, although I think I added in the larger discussion about poetry from Gillian White and Ben Lerner at a later date. And the final list of italicized questions at the end of the book have always been the same, with one substitution—“What else can I feel…the city, its tallest buildings and its ruins, its young and its old, its pet cats and cars?” Used to be pet pigs rather than pet cats. In its original version, the tail end of the manuscript took place in New Orleans, where I definitely saw pet pigs (this never happened in Providence). As a result, the final page now emphasizes cats twice, which is fine—all of my books have to have cats in them.

So, in short, I always had my beginning, and I always had the very very end. But what comes between is the difficult part; that has always been my struggle with writing. How can the messiness and expansiveness of human experience be condensed down to the elements that matter in a particular book and for a particular character? That’s still something I struggle with.

This year, I’ve read some books that have helped me think about it in new ways. Deb Olin Unferth’s Barn 8 has been really important (I know you’ve written about this one)! I have chickens, so that drew me to it, and I learned a lot about them, but on a narrative level, I loved how the character study spiraled and exploded to include more and more people in longer and longer timelines alongside the chickens themselves, allowing animals to have just as much narrative importance as people, and in doing so, showing how a “character arc” is only one kind of possible narrative (and that perhaps we need to pursue others in the Anthropocene).

Some other favorite books from this year that turn conventional ideas of the novel on its head are Sheila Heti’s Pure Colour and Lindsay Lerman’s forthcoming What Are You.

I also recently read Caitlin Barasch’s A Novel Obsession, about a young woman who starts stalking her boyfriend’s ex-girlfriend to get material for her novel. That one showed me a lot about what I did wrong in the first longer novel I attempted (there’s an excerpt in Joyland), and I’ve felt called to go back and try and fix it, although I thought it was basically dead-in-the-water and it is certainly not what I am “supposed” to be working on. I’m supposed to be working on a near-finished novel about a commune and a proposal for a nonfiction book called Psychoanalysis for Cats about the existential questions that arise when you live with and love cats.

I still don’t know what the right approach is—going back to the project you finally understand and trying to resolve those questions for yourself (and, potentially, for a readership), or pushing forward and hoping the next thing turns out better. But maybe you need a bit of both, a bit of back-and-forth, and to stay open to whatever wants to come out next.

With gratitude,

Rebecca

This post may contain affiliate links.