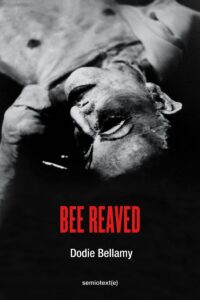

[Semiotext(e); 2021]

Dodie Bellamy is not one for formal writerly prescriptions. She is suspicious of polished, correct, and controlled language — the kind often bred in workshops and found in canonical literature. Refinement leaves her cold as it erases the “libidinal pressure” that fuels the writing process. Instead, Bellamy advocates for raw expulsion and self-exposure: “The best writing embarrasses the author — at least a tiny bit — emerging from a compulsion to flaunt what any sane person would camouflage.”

Flaunt she does. Bellamy luxuriates in the vulgar and abject, and she returns, time and time again, to the body. This is true of all her work, and Bee Reaved, her new collection of essays, is no different. She discusses fucking, belching, pissing, and, most of all, shitting. Excretion is a major leitmotif in the collection — sometimes mentioned in passing (a little jolt delivered through a simile: “carefree as dogs rolling around in shit”) and other times delved into with great vigor. In one essay, Bellamy reads an entire book, Marie Darrieussecq’s Being Here is Everything, on the toilet. Through these designated trips to the bathroom, she seeks to eliminate barriers to intimacy between herself and the book, accessing a state Julia Kristeva termed “jubilatory anality,” the ecstasy of dissolved personal boundaries.

Creation, for Bellamy, is as physical as it is mental. Fully inhabiting her body enables her to transmute the sensuality of present experience into written word. She embraces materiality, considering it an anchor in the throes of enveloping abstraction. But materiality also betrays, unmoors, devastates: bodies inevitably deteriorate.

Much of Bee Reaved follows the loss of her husband of thirty-three years — the poet Kevin Killian — and the new life she must navigate in his absence. “Widowhood is an anti-space,” she remarks, a void formulated by a prevailing sense of lack. Love without an object bewilders, effectively rendering the material world unreal. Bellamy compares her object-less love to “a migratory bird that has lost its instincts.” “If someone’s going to die they should take the love with them, not leave it behind, confused,” she adds.

During the first year or so following Killian’s passing, Bellamy’s love hangs static in the air. She neither tucks her grief away nor immerses herself within it. Bellamy turns her marriage over in her head with a certain degree of aesthetic distance, inspecting its plausibility, veracity, and value.

Her fugue-like grief state is exacerbated by the lockdowns of COVID-19 — the first of which is enforced just seven months into her widowhood. The entire world in shock, her exterior and interior lives begin to mirror one another, generating a peculiar flattening effect. In an essay that describes this period, Bellamy switches to third-person narration, filtering her mourning through her widow persona, the titular “Bee Reaved.” (This persona was created by her friend Mattias, who had the foresight to tease, not pity, Bellamy.) Bee’s unstructured days and roving thoughts are broken up by bodily need — that of her own and of her cat. When horny, Bee attempts to put off masturbating but eventually succumbs to the urge, wielding a vibrator to target “a spot inflamed and tense as a zit that’s ready to burst.” And when confronted with her cat’s spells of diarrhea, she dutifully attends to the messes: “Bee’s senses are assaulted, over and over and over. Brute repetition replaces an entire system of meaning.”

The body persists in needing, regardless of the meaning — or lack thereof — attributed to the need. This business of relentless needing can be tedious, but then, it also fuels and guides existence. (Relentless need — can’t live with it; can’t live without it!) And so need fuels and guides Bellamy’s grief, and she admirably ‘trusts the process,’ following its circuitous path. She watches Grey’s Anatomy, rebukes her past selfishness, forgets, composes witty texts, remembers, cries, and, eventually, accepts that her life goes on: “I GO. I BETRAY. I’ll always come back.”

While Bellamy’s loss is the driving force behind Bee Reaved, the essays aren’t limited to her personal tragedy. The first half of the book features pieces drafted before Killian’s death and covers a variety of subject-matters: art, aging, ghosts, and working class America, to name a few. All the essays grapple with loss in its different iterations, exploring how people attempt to stave off or reconcile themselves with death, grief, and pain.

“Hoarding as Écriture,” for instance, posits that writing, like hoarding, is a means of self-constitution and preservation. The dozens of journals Bellamy has devoutly filled with “fleeting thoughts and emotions” serve as proof of her existence, and her published writing secures her relevance within a subset of the literary world. To remember and be remembered, then, is Bellamy’s proposed antidote to mortality.

So, she spews words onto the page, and then spews again and again. Her desire to release and record often strikes her as insatiable in the moment. But Bellamy is unapologetic about her maximalist, meandering prose, invoking the steadfast feminist argument that for a woman, daring to be “too much” is a form of resistance. She “takes up space” by hoarding the nonessential and repetitive — the stuff many editors would whittle away. As a result, Bellamy’s work often reads like a series of intimate conversations with friends: the same themes rearticulated, the same epiphanies re-realized. Then comes a passage so crystalline and resolute that the reader-author relationship is reestablished and sanctified. These bits of concision remind the reader that Bellamy knows what she’s doing: surrendering control over her prose is a conscious decision, a different way to exercise agency; she can reign it in whenever she chooses. By emptying herself into her writing, Bellamy holds the fullness of her being to the light. Her illuminated self now exists independently, contained within an object-form, carrying on a life that will extend far beyond her own.

In another essay, “The Violence of the Image,” Bellamy shares her brush with cancel culture — without, mercifully, lapsing into a polemic. Her canceler is a young woman who runs in a San Francisco poetry scene Bellamy was once a part of (before the canceling in question). Initially a fan, her admiration curdles into contempt when she takes offense at a comment Bellamy leaves on another poet’s Facebook post. So begins the smear campaign. And then the stalking. In a bizarre method of attack, she orders miscellaneous, relatively benign products for Bellamy online. They are not so much objects as images, or “suburban talismans,” including lawn plants, frilly dresses, felt Christmas ornament kits, and fish pond water conditioner. Imagining her stalker as a composite of these purchases, Bellamy weaves a pulpy narrative about her life: a bored, ravenous housewife whose noisy sexual liasions are insulated by overgrown hosta plants. Bellamy can’t help but animate the assemblage of objects, situating them — quite squarely — at the intersection of capital and desire.

Bellamy then pivots into a psychological mood, postulating that when shopping compulsively online, her stalker’s sense of linearity collapses: the past encroaches onto the present, catapulting her into the “now now now of spurting adrenaline.” Riding the rush of expansive timelessness, her stalker directs her illegible rage towards her target, but what she really seeks to destroy, Bellamy divines, is the “stink of trauma that wafts off of her.” Treating another person like an image, as Bellamy’s stalker does to her, is an act of violence, inviting projection of inner wounds. Bellamy’s inclination to narrativize and character-build is arguably a form of projection, but, critically, she transfigures muddled bits of reality into art, which exists at a distinct removal from life. (She also isn’t engaging in harassment.) While her stalker tries to elude her pain by pinning it on another — which keeps her stuck, treading in misdirected hatred — Bellamy metabolizes her pain by ejecting it on the paper, carving out the space for self-renewal.

Punctuating these front-end essays are conversations between Bellamy and Killian about exhibitions they’ve attended together. Killian’s worsening illness silently looms over these dialogues, casting every memory recalled, every idea voiced, in a sacred light. In the second half of the book, which narrows in on Killian’s last days through the aftermath of his passing, the couple’s discussions are periodically interrupted by flares of despair; Killian’s pain restructures the intellectual exchanges at hand. Immense tenderness accompanies the despair, however, inching Killian closer to a state that approximates peace.

This interplay between intellect and affect is absorbing to read and testifies to the profound singularity of Bellamy and Killian’s partnership. Their marriage was highly idiosyncratic — unadvisable even. Bellamy acknowledges that Killian was a “horrible choice”: “An alcoholic homosexual who’d never had a mature relationship,” she deadpans. But they could really talk, and Bellamy doesn’t believe in conducting her life in accordance with rationality or wisdom anyways. Neither did Killian, who practiced and preached “radical amorality.” As a couple, they didn’t hold themselves to the expectations of a “good relationship” (affairs were sanctioned) nor did they endeavor to fully understand one another (decidedly impossible). Through their iconoclastic approach, they forged a steadfast love: two nonconformists bound by matrimony in sickness and in health. Bee Reaved is not a formal tribute to Killian, but it is a tribute to loss — to seeking “endless potentials” through absence and emptiness, such as those Bellamy’s late husband inspired.

Caroline Reagan reads and writes in New York City.

This post may contain affiliate links.