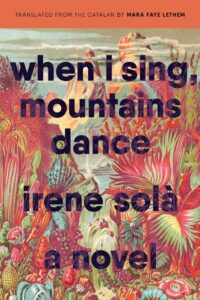

[Graywolf; 2022]

Tr. from the Catalan by Mara Faye Lethem

I saw the Pyrenees once, when I was living in southern France. I knew the scale and scope of the mountain range lent a natural barrier between Spain and France, and I come from California, where our mountains are bigger than the East Coast counterparts. Yet nothing prepared more for the sheer size of the Pyrenees, the setting of Irene Solà’s When I Sing, Mountains Dance. I passed by in a car, getting only the most cursory view of the mountain range, which extends as deep as 80 miles in its center. If in my life the mountains were only ever a distant rupture on the horizon, Solà’s novel affords the region a profound sense of humanity. Ghosts of the Spanish Civil War appear in several chapters, commenting on how the fresh mountain air does a body good, “especially if the top of your head’s been blown off.” And so begins a polyphonic book designed to imbue the mountains, its animals, and its inhabitants with a rich history ruled by death.

When I Sing, Mountains Dance opens with a man — Domènec — struck by lightning “so bright and so dazzling that it sated all need for seeing.” Four witches, utterly indifferent to his death, pick up the black chanterelles he dropped and move on. This moment sets the scene for a major theme in the book: the indifference nature has towards people, callously accepting that death comes to all. The humans who live in the mountains, by contrast, spend their entire lives processing their grief.

“The mountains took Domènec from me,” says his wife, Sió. She laments that in all the promises she made to him, she never agreed to raise their children on her own. But with Domènec’s death, Sió is left with two children. “Why would a woman want just the children? I barely got to taste him,” she asks in her grief. And though Sió raises her children as a single mother, she never gets over the death of her husband. Nothing, she thinks, can replace him: “Eight years and I’m still not over it. This damn void won’t fill with resin. Because I married the most handsome man in these mountains.” And she calls her children weights on her back that won’t let her die. When I Sing, Mountains Dance demonstrates how bitterly difficult it is for humans to process a loved one’s passing. Death, Solà tells us, will always be resisted by mortal beings.

This message is most apparent when the novel takes on the voices of fungi and animals in the mountains, who face and process death in their own ways. “The spores of one are the spores of us all,” the immortal black chanterelles say. “Because we have been here always and will be here always. Because there is no beginning and no end.” In another chapter, the mountains themselves discuss their formation and the death caused by the slamming of their tectonic plates. Though their backs offer a haven to creatures looking for a home, the mountains pity the “poor, miserable wretches” that struggle to survive. In another chapter, a roe deer is separated from its mother as a fawn. Though fear of death takes up residence in the fawn like a disease — aligning humans and prey animals — it fights to keep living.

In reading When I Sing, Mountains Dance, I wanted more of the witches, of the deer, of the fungi and the mountains. Since the novel reads like a folktale, its writing works best when playing with the perspectives of nature. Its shortcomings were especially apparent with each new chapter narrated from the perspective of a human. Other recent polyphonic novels made pains to distinguish each character: Bernardine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other (2019)was written from the perspective of women with distinct identities and upbringings that came through in the free indirect style of the prose. Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing (2016) took place over eight generations, easily setting each voice apart from another. By contrast, most of the human narrators in When I Sing, Mountains Dance are contemporaries living in the same village, leaving the reader to guess who is narrating each chapter. I found myself wanting more of the surreal voice Solà lent to the mountains.

The setting of the Pyrenees gives When I Sing, Mountains Dance an ancient feeling, as though this story could be happening at any point. That is, until modern references like the electric fence and Facebook and nightclubs push their way into the novel. They remind the reader that the book is set in the present day. That the pain and fear experienced by the animals and humans is not only timeless but felt today. At one point, a hiker passes through the town, calling the area “authentic” and “frozen in time” and “so chill” with no real understanding or empathy for the people who live in the Pyrenees. He demands bread from the townspeople as they take the day off to mourn a neighbor’s death. His callousness serves as a reminder that another’s lived experience is not something understood just by passing through their town (or driving by, as I did). Death comes to us all, but we cannot pretend to understand how the long goodbye impacts someone whose life we know nothing about.

Grief, which never lets go of Sió, takes hold of her daughter, who finally ends generations of sorrow by forgiving the man who killed her brother. But first, she “flares up, angry as a mountain,” and says she is sorry it was his fault her brother died and that his death destroyed everything. And then she recognizes that just as his being sorry is not enough to heal her pain, her love was not enough to save her brother. There is a kinship to their powerlessness. And in the background, the Pyrenees pity the humans that took multiple generations to find forgiveness and make room for healing. To truly understand the mountains, to truly understand another person, Solà tells us, you must make time to understand them. Otherwise, they remain a sort of landscape painting, a romantic ideal of rural life. When I Sing, Mountains Dance is a novel brimming with hope for future generations, and for the vitality of the Pyrenees mountains.

Brianna Di Monda is a contributing editor for Cleveland Review of Books. Her fiction and criticism have appeared or are forthcoming in The Brooklyn Rail, Litro Magazine, and Chicago Review of Books, among others.

This post may contain affiliate links.