This essay was first made available last month, exclusively for our Patreon supporters. If you want to support Full Stop’s original literary criticism, please consider becoming a Patreon supporter.

When I found G’Ra Asim’s epistolary essay collection, Boyz n the Void: A Mixtape to My Brother (Beacon Press, 2021), I didn’t believe the book existed. Most people are not Black. Most people are not punk. Most people do not write books. Even fewer all three.

Asim, a thirty-something writer, a member of the DIY pop punk band babygotbacktalk, and an assistant professor of English at Washington University, anticipated my disbelief. In the book’s second essay, he recalls his time in mostly white creative nonfiction graduate workshops, writing: “Our audiences have not been inundated from birth with primers for our proclivities. I have been hamstrung by the fact that in order to conjure a literary photograph of myself, I must first prove that I exist.”

I never doubted the author’s existence or capabilities; what surprised me was that the notoriously homogenous publishing industry brought his book into the world. My initial wonder at Boyz n the Void was cynical and self-protective—I thought it too good to be true. But with his very real debut, G’Ra Asim joins Hanif Abdurraqib, Laina Dawes, Chris L. Terry, and Dawnie Walton in writing about alternative rock from a Black perspective, one which requires deep engagement with a world that does not always extend them the same careful consideration.

The result is a testament to the power of subjectivity within group identities—a compelling, conflicted, and appropriately specific portrait of the intersection of Blackness and punkness. The particulars of Asim’s perspective shine through in the book’s form, the doubly intimate mixtape-as-memoir, and in its content, his points of reference therein: Hegel, Margot Jefferson, and others of their esteemed ilk, in addition to the usual punk suspects, from Minor Threat to Masked Intruder. “Any good mixtape is indebted to this ethic of discerning but miscellaneous accumulation,” Asim notes. There’s nothing more punk than making your own rules, after all. Asim has done just that, with the mix of stubborn conviction and radical openness that makes the genre so compelling.

When Asim introduces his brother Gyasi, fourteen years his junior, the youngest of their five siblings and the one to whom the book is addressed, Gyasi isn’t interested in schoolwork or socializing. Standard teen angst. But basicness is not an option for the Asim children. They are the progeny of proud Black intellectuals who labored to move their family from a St. Louis “ghetto” to a suburb of Silver Spring, Maryland when Asim was an adolescent. Baba, as Asim calls their father, and the Black Momba, as he affectionately calls their mother, “fancy their home as a factory of black excellence,” not an angst mill.

Asim buys into this self-mythologizing even as he fights for the Asim kids to have wide-ranging emotional lives. He describes their clan as an updated version of J.D. Salinger’s fictional (white) Glass family, and wants to craft for Gyasi his own version of the pep talk older brother gifts to younger sister in Franny and Zooey. Asim must assure Gyasi that “a roadmap to self-actualization exists” for people like them—people whose expectations for themselves are at odds with society’s plans for them.

In light of the pressure from their parents to be extraordinary, Asim’s complicated relationship with what’s expected of him is unsurprising. He looks beyond his own family and writes, “Black people’s relationship to normalcy is admittedly hard to parse.” Othered through no choice of his own by an arbitrary standard of whiteness, and voluntarily by his rejection of mainstream music and again by his pursuit of a career in the arts, Asim seems to regard otherness with indifference or grudging acceptance. In other moments, he cheerily curates his outsider status. The result can be dizzying. One cannot celebrate abnormalcy and be indifferent to normalcy. Neither exists without the other.

This tension allows Asim to interrogate what’s been deemed typical for young Black men—their hobbies, gender expression and sexuality, speech patterns, professional aspirations, political strategies, drug use, emotional lives, and of course, aesthetic allegiances—in contrast to (and sometimes in line with) his actual experiences. Thus, the ten-track annotated mixtape that is Boyz in the Void is born, and passed from brother to brother. It’s an invitation to discover music and wisdom Gyasi may appreciate, not an imperative for what he, or anyone else, must live by.

A counterculture by nature, punk is concerned with differentiating itself from the dominant culture against which it defines itself. But punk is ultimately welcoming behind its gatekeeping—unlike whiteness, which must remain exclusionary to retain its power. For those who find obscurity inherently cool, punk may be aspirational, but for many, its existence is neutral. For others, punk is more than a musical genre. It is a lifestyle, an ethos. Punks often refer to their origin stories in life-or-death terms, reminiscing about how punk saved, not just changed, their lives. For many, punk is foundational to one’s identity to a degree such that it might parallel to something as unchangeable as race. The writerly identity can be just as absolute.

Many people dream of becoming published authors from a young age. They speak of writing as a passion and imperative: whether they are published or not, they must write and so they are fundamentally writers, just as someone can be essentially Black or punk. But this dedication to a self-expressive and artistic pursuit, and to books—the objects which it produces, is also tied up in both egalitarianism and gatekeeping. Most aspiring writers aspire to publish a well-received book, i.e. obtain a publisher and or audience’s cosign. Yet any author or person who works in publishing can tell you that the road to getting one’s work published is anything but meritocratic.

All three of Asim’s most salient identities—Black, punk, writer—inhabit the same contradiction, in which a status can be desirable, highly influential in the mainstream American cultural consciousness, and simultaneously belittled and ignored. Non-Black people are free to appropriate or devalue and dismiss Blackness at their whims. Meanwhile, punk is both a seductive means of accessible, egalitarian rebellion—such that people often invoke a nebulous punk ethos outside of the context of any actual punk music—and an exclusionary or irrelevant niche with no bearing on most people’s lives.

To be Black, or punk, or a writer, does not make one cool or morally good automatically. However, all three in concert make one relatively unique. Asim explains in the book’s introduction that “a robust engagement with counterculture can serve as a vital antidote to soul-sucking normalcy.” The kneejerk inclination toward rebellion feels adolescent, though not inappropriate for a punk mixtape. But Asim is also wary of the way that alterity is operationalized, rhetorically, in a range of political quarters. As he later observes, “this shared disdain for normalcy is one locus of the unnerving synchronicity between punk culture and the latest iteration of virulent conservatism. … Punk rockers and the alt-right both fancy themselves as footloose fringe dwellers resisting a somnambulating middle. (People who call themselves ‘woke’ are operating from a similar premise.)”

The common ground of conservatives and self-proclaimed woke type whites is on display in Boyz’s opening chapter. “Africa Has No History: An Annotation of Anti-Flag’s ‘A Start,’” is one of the book’s best, as the ever-political Pittsburgh band provides the soundtrack to Asim’s and Gyasi’s twin struggles with racism in education. Gyasi’s sixth grade history teacher, a square white man, claims that Africa “has no history.” Years earlier, Asim’s twelfth grade AP Literature teacher, a liberal white woman with the same dyed-orange hair as Asim, dismisses him when he challenges her assertion that Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (or any single book) is the cornerstone of African American literature. These teachers’ stories about stories are the first of many against which Asim rebels.

He notes that Joan Didion’s famous quip that we tell ourselves stories in order to live only gets Black people so far, and as “Africa” continues, it establishes the book’s project of proposing and critiquing our existing library of Black narratives, and how we might expand it. One alternative means of self-narrativizing is “black normcore,” whereby a white story is retold with Black characters but without further changes, as seen in Jay-Z’s long form music video for “Moonlight,” in which Black comedians stand in as the cast of Friends. Asim deems this instance of black normcore a rare success because it is self-aware: one of the comedians calls the project ineffective.

He otherwise disapproves of Black art in which a popular piece of media or cultural touchstone is remade or reimagined by simply changing the race of its subjects, with minimal or no nuance or deeper subversions. Per Asim, non-credible attempts at black normcore include Kenya Barris’s tame ABC sitcom Black-ish, Rachel Lindsay’s tenure as the first Black lead on ABC’s The Bachelorette,and Herman Cain’s status as highly visible Black Republican, all of which are more interested in reforming the status quo than exploding it and rebuilding something else in its place. Asim connects his disappointment in black normcore to the supposed profundity of Saul Bellow once asking, “Who is the Tolstoy of the Zulus?” Both assume white culture, on the page, the screen or elsewhere, is the gold standard against which all human achievements must be judged and suggest that Black-ified approximations of white excellence are the closest Black people can come to brilliance.

Strangely, Asim includes Issa Rae, one of the comedians in the “Moonlight” music video, and her HBO series Insecure (whichfollows a group of four Black women in Los Angeles navigating friendships, careers, and dating) under this umbrella of failed Black subversions of white narratives. Rae co-created, executive produces, stars in, and often writes—i.e. has significant autonomy over—the show that catapulted her to stardom. It is just as much, if not more, in conversation with Black shows like Girlfriends and Living Single (which Asim references at one point) as it is with white shows like Friends and Sex in the City. Insecure is not wildly original in its premise, but it at least notably features a variety of dark-skinned Black people, especially women, in leading and fully realized roles, whereas other popular television shows disproportionately center mixed-race and light-skinned Black women.

Rae’s professional trajectory and public persona may not achieve Asim’s brand of radicalism, but they may not aspire to it at all. As far as I know, her proclamations about her own abnormalcy comprise little more than the branding that defined her early in her career, when “The Misadventures of Awkward Black Girl”served as the title of her 2011-2013 web series and her 2015 bestselling memoir. In addition to or instead of focusing on Rae as a negative example, Asim could have given a more productive, positive nod to Random Acts of Flyness, another HBO comedy series with a Black creative team (this one led by Terence Nance), which is much stranger than Insecure (and most other television), often wonderfully so.

Still, Asim takes the time to declare Rae’s work insufficiently awkward or other. Yet he does not, in “Africa” or elsewhere in the book, offer a parallel explanation of his own career decisions. In light of this, his criticism of Rae’s choices seems unbalanced because we are told so little about his own.

Outside research reveals that as an educator, Asim’s ambitions as creative writing teacher include “build[ing] a program focused on antiracism education,” and that he views both teaching and literature as a form of performance. In another interview, he also describes his investment in challenging the status quo in “productive ways” through his punk-inflected writing and teaching practice. But such explanations are not to be found in Boyz, which instead focuses on Asim’s coming-of-age. Nor does the book offer anecdotes about how Asim navigated the publishing process. Readers may be inspired by the existence and quality of his work, but he doesn’t offer concrete information about his path to becoming the kind of literary citizen who’s hosted a conversation with Colson Whitehead and written for The New Republic, The Baffler and Guernica and elsewhere, on top of writing a book. There’s no discussion of whether working with Beacon Press, a risk-taking independent press, was a pointed rebuff of more mainstream corporate publishers, a happy coincidence, or a combination of the two, or if his father’s publishing history and media bona fides had any bearing on the process. Such information would make his own stories about storytelling more compelling.

Asim instead homes in on an interview in which Rae discusses plans for a new project about Black teenagers, one akin to 90210 and Gossip Girl—and Moesha. Asim doubts Rae’s new projects will “accommodate someone like [his brother Gyasi], even as she advertises them as [his] home turf.” Asim’s assumption is difficult to contend with because Gyasi’s characterization in the book is frustratingly thin. Details about him are scant, perhaps out of respect for his privacy, or in order to make it easier for any reader to imagine themself as Asim’s audience, mentee and confidant. We know that Gyasi struggles academically and socially in school, though perhaps somewhat intentionally as a form of rebellion. But Asim doesn’t clarify what makes younger brother, and by implied extension, older brother, so essentially incompatible with Rae’s work (gender? parental influences? aesthetic?) Most likely, it has something to do with Rae’s desire to depict regular Black people in regular ways, as opposed to Black outcasts like the Asim brothers. This is ironic, as Asim here is engaging in precisely the sort of flimsy romanticization of otherness which he decries elsewhere in the book, allowing that the punk subculture can at times resemble an “echo chamber…dressed up in a hollow guise of dissent.”

Poet and critic Fred Moten shares Asim’s reservations about the paradox of mainstream unconventionality, vis a vis how Rae and other “so-called black nerds” Donald Glover and Neil deGrasse Tyson have become the pinnacles of black weirdness in the popular imagination. Moten similarly questions why Blackness and weirdness are often pitched as an unlikely combination, rather than a natural one, and is also somewhat vague in citing Sonny Boy Williamson, George Clinton, and non-celebrities from his neighborhood as more appropriate ur-Black weirdos. Alas, it’s difficult to blame them; to demand or disseminate a blueprint nonconformity is yet another contradiction. But by not being more forthright about the specific ways in which media might better reflect his and Gyasi’s lives, Asim risks overestimating, misunderstanding, or misrepresenting his and his brother’s uniqueness. It’s an admittedly minor offense in the face of society’s neglect of their needs, but in an intragroup Black context, it’s important to acknowledge this folly for what it can lead to: another instance of outsider precarity as self-mythology, which harkens back to Asim’s frustration with punks and conservatives and anyone who uncritically identifies with their chosen otherness.

Mikki Kendall, author of Hood Feminism: Notes from the Women That a Movement Forgot, consistently challenges the narrative that nerdy Black children who are alienated from their Black peers are necessarily victimized because of their intelligence or uncommon interests. In a series of tweets, she reminds us, “Sometimes I got bullied. I could claim it was because I was smart. Mostly it was because I was awkward… I could pretend the bullying was unfair & never my fault… Some of it was unfair, some of it was a reaction to me being really arrogant.” She encourages those with similar experiences to work through their complaints in therapy rather than publicly pushing a false narrative about Black culture as anti-intellectual and stoking unproductive in-fighting among Black people. Asim tirelessly paints Black people as intellectuals, and his unconvincing analysis of how consequential Rae’s moves toward or away from rebellion are does not necessarily count as the antagonism Kendall references. But for Asim to not acknowledge the moments in which he is guilty of relying on stereotypes or tropes, about women posing as part of a counterculture for social or monetary gain, is in opposition to his stated purpose.

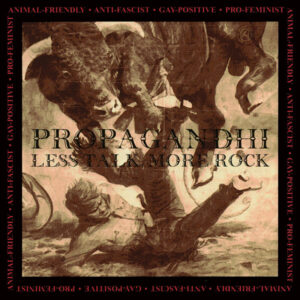

After Asim dismisses black normcore, his next chapter, “Evidence of Things Unscene: An Annotation of Propagandhi’s ‘Less Talk, More Rock,’” endorses alternatives like Afrofuturism, which spans disciplines and mediums, and steezpunk, a descriptor he uses for his own band: “A smarter, jauntier spin on punk pop. Boisterous and irreverent but with an emphasis on wit.” Most importantly, across chapters, Asim approves of and aspires to “queering” the canon—that is, the “imaginative reconstruction of race and blurring of consensus categories,” as described in Elizabeth Chin’s 1999 essay “Ethnically Correct Dolls: Toying with the Race Industry,” in which she observes Black girls who are content to treat white Barbie dolls as Black by putting their hair into traditionally Black styles. Giving the girls carefully manufactured official Black Barbie dolls (various iterations have been available since the late 1960s) whose Blackness was coded in predetermined ways, independent of the girls’ input, would have been an act of Black normcore. But this more imaginative, individualized play, Chin argues, is more important to understanding how race operates.

Asim’s engagements with literature and punk walk the line between normcore and queering. Fancying himself a Zooey Glass type and delivering a pep talk to his Franny-ish sibling could be a mere act of normcore. But rather than perpetuating the old with a simple surface-level race change, he queers Salinger’s fictional portrayal of white sibling mentorship by both drawing from its precepts and making it his own. The nonfiction mixtape memoir of a Black life is a new genre, true to his individual experiences, and likely more transgressive than a more faithful riff on the book would be. We also learn that as a teenager, Asim had fun with assumptions about Black intelligence, per a homemade card in his wallet that identified him as a “Card-carrying member of the radical punk rock intelligentsia.” This is not a large or groundbreaking rebellion. In fact, it’s quite normal behavior from a precocious punk kid (some might call it Black normcore). But part of the beauty of adolescent angst lies in its exaggeration of its uniqueness. “Evidence” champions individuality while acknowledging the alienation it can bring, though in the best cases, it also inspires community. Asim identifies with the Afrofuturism’s literal extraterrestrials; his sister does the same. Later, he discovers a Black punk band, Aye Nako, that does too.

These happy moments are not the whole story. The following chapter, “Marching Through the Mosh Pit An Annotation of Operation Ivy’s ‘Room Without a Window,’” details Asim’s initial foray into punk following a sports injury. Craig O’Hara’s book The Philosophy of Punk, discovered at one of his father’s literary events, naturally attracts Asim’s intellectual side, but his father struggles to recognize the artistic merit of ska lyrics. Later in life, a non-Black woman of color is taken aback when Asim dances to an emo song “like” he’s Black. Things do come back around when he proudly observes that the ethos of the recent and ongoing Movement for Black Lives is more punk than that of the midcentury Civil Rights movement, per its move away from indulging respectability politics and toward declaring one’s humanity unassailable regardless of circumstance. In the chapter’s final lines, he assures Gyasi that “permission to fully inhabit our humanity isn’t something we need to ask anyone for. It is our birthright.” Unfortunately, it’s more idealistic than realistic.

For Black people, the opportunity to explore and indulge non-racial angst is a sacred but not always convenient or respected imperative. An especially harmful limit of stilted popular narratives about Black people is their tendency to depict Black suffering, and prioritize and frame such projects as necessary to prove the existence of anti-Blackness to non-Black audiences. This is often coupled with a celebration of Black resilience over indictments of those who create the unjust conditions that Black people must subsequently overcome.

Blackness under white supremacy warrants a generalized angst so undeniable that it is often reclassified as trauma. This further traumatizes Black individuals and communities if it overshadows Black people’s experiences with the lower stakes, fleeting personal angst commonly associated with white teenagers. But this frivolous angst—in which hardships soon prove inconsequential and difficult-to-process feelings are soon outgrown—is Black angst too. To deny this is to deny Black people full personhood, a malady for which Black punkness provides a possible remedy.

When low-level Black angst is acknowledged in the media, it often leans into its supposed strangeness. In a 2005 episode of Girlfriends (“Judging Edward”), straight-laced lawyer William must return home and spend time with his emotionally closed-off father following his mother’s hospitalization. He calls his friend and coworker Joan for advice, and she explains that she turns to different genres of music for different kinds of problems. Punk is for parent problems: “Those little punks are always talking back to their parents.” The subtext being that white people aren’t required to treat their parents with the same unwavering and performative respect that many Black people default to. Thus, white people are more able and willing to access a broader range of emotional and psychological states more safely and comfortably than Black people.

Joan recommends William upend these assumptions by listening to “Perfect” by Canadian pop punk band Simple Plan (of course the more “punk” choice would have been the Descendents’ “Parents”). William is skeptical that a “grungy punk” can speak to a conflict between Black men that is ultimately rooted in slavery. Moments later, he admits, mouth open in disbelief, “It’s like they’re reading my mind.” The bit works because it queers punk into something that can fulfill the needs of a Black person in a given moment. The band did not intend William as their audience, but he can utilize the music for his benefit regardless. To the already indoctrinated Black punk, William’s positive response to the music is just as funny as his facile assumption that the genre wasn’t for him.

Over fifteen years later, it’s increasingly common for Black people to find obviously Black and non-Black ways of embracing and wallowing in all levels of angst—in jest, with gravity, and everything in between. One of the many pieces examining Black millennials’ “unlikely” love of pop punk band Paramore frames a Black interest in punk and emo as a reclamation of the Black origins of rock music, as we enter into a “new post-emo, rap-rock era featuring tons of angst and feelings.” In an interview with Dazed, Princess Nokia similarly cites the Black-created blues tradition of prioritizing (often negative) emotionality in personal and political affairs alike: “There’s a vulnerability in associating with pain and sadness that has always lived in that narration.” She aims to continue those traditions by creating and championing intersectional emo, as a communal political and self-serving act. Willow Smith recently released, to much fanfare and acclaim, a pop punk-influenced album featuring collaborations with Avril Lavigne and Blink 182’s Travis Barker, as well as Smith’s fellow Black woman Tierra Whack. The album and song titles alone unabashedly indulge her frustrations: lately i feel EVERYTHING. “F**K You.” “don’t SAVE ME.” And so on.

But if one does not (understandably) like the acoustic qualities of punk music, the same egocentric Black angst is present in more “obvious” places as well. In an episode of the The Nod podcast about Crime Mob’s 2004 humbly-made track turned raucous anthem “Knuck If You Buck,” co-host Eric Eddings contextualizes the appeal of the song, which was recorded when the group were teenagers. Eddings loved his adolescence because of the range and intensity of his feelings at the time, he says:

Imma call it angst…which to me is important because when people talk about angst they don’t ever associate that as a thing that Black kids have…If there’s any group of kids in America to have angst, it would certainly almost be us…[“Knuck If You Buck”] captured what I feel like a lot of Black kids who grew up in areas like mine was feeling at that time: trapped.

Just as lite Black angst may always exist in the context of larger racial trauma, angst of all kinds is inseparable from broader concerns about mental health. But the point at which angst becomes pathological and dangerous, rather than simply puerile, is as elusive as the other conceptual relationships in Boyz. In the achingly astute chapter, “Mad Props to Madness: An Annotation of Bad Religion’s ‘Pity the Dead,’” Asim recalls how he and a white friend shared a “mutual fascination with suicide.” But his friend wasn’t interested in Bad Religion’s takes on large-scale sociopolitical discontent, and preferred the lighter antics of Blink 182. Meanwhile, Asim is inspired to connect Bad Religion’s concern for the dispossessed with Langston Hughes’s poetry. He lands on the heartbreaking reality that in a racist society, “the colloquial understanding of craziness made it difficult to imagine a wide gulf between mental illness and progressive nonconformity.” It is only in an ideal or surreal world that difference will exist without a malignant power structure in any direction. Even within the world of the self, the tension between difference and power is inescapable.

When rhapsodizing about Afrofuturism, Asim marvels that within it, “Different mustn’t always mean marginal.” For punk at large, though, it likely must. This does not mean that all punks must reject meaningful financial stability and other comforts, or recognition that is not purely in-group, but that punks must always embody some degree of chosen marginality, tangible or symbolic (preferably both) in order to align themselves with the genre convincingly. For Black people, and anyone else who is othered regardless of their taste in music, choosing difference vis a vis punk and its subsequent marginalities, creates space for an ideal angst. Black punk is not only possible, it is necessary for the betterment and sustainment of both Blackness and punkness.

The most haunting moment Asim shares is not one of the casually ignorant or roaringly racist comments or face-to-face interactions others force him to endure. It is a private moment in which he second guesses himself. After rightly lamenting that outspokenly “Animal-Friendly, Anti-Fascist, Gay-Positive, Pro-Feminist” band Propagandhi doesn’t include “Anti-Racist” alongside the aforementioned declarations on cover of their 1996 album Less Talk, More Rock, Asim wonders if his callout is “a petty ax to grind.” It is not. Full stop. But his hesitancy is both weird and all too familiar to Black folks. For him, Blackness and punkness are both ultimately about “siding with the weak against the strong” and his memoir is a vital artifact of community between brothers and strangers alike. Just as Boyz affirms Asim’s existence to me, I want to remind him that I exist too. That I love that album too. And there are more of us out here in the void, reading and listening. We may not agree on everything, but I can promise him this: punk that isn’t anti-racist and pro-Black isn’t punk. Tell everyone.

Mariah Stovall is a literary agent and writer from New Jersey. She’s written fiction for Ninth Letter, Vol 1. Brooklyn, Hobart, and Joyland and nonfiction for Catapult, The Paris Review, Poets & Writers and Literary Hub. She tweets @retiredpunk.

This post may contain affiliate links.