Dodie Bellamy’s essays have a muscular force. Seamless and shimmering, each piece is constructed like a snake. Her new collection, Bee Reaved, comprises works selected after the death of Kevin Killian, her partner of thirty-three years, and explores grief, isolation, social media, and a variety of aesthetic experiences, from art exhibits to television shows, with her customary intimacy and verve.

Dodie Bellamy’s essays have a muscular force. Seamless and shimmering, each piece is constructed like a snake. Her new collection, Bee Reaved, comprises works selected after the death of Kevin Killian, her partner of thirty-three years, and explores grief, isolation, social media, and a variety of aesthetic experiences, from art exhibits to television shows, with her customary intimacy and verve.

Even a partial list of the subjects she treats in these essays would be dizzying: archivists, internet stalkers, housework, ghosts, sex, The Little Rascals, endoscopy, selfies, Marie Darrieussecq, Mike Kelley, Grey’s Anatomy, cat shit, dreams . . . As with snakes, it’s not the individual scales that count, however shiny. It’s the way they’re put together. Bellamy’s gift for connection and association weaves a multitude of diverse topics into a vital tissue, filled with insights and the pleasure of the unexpected.

In a shared Google document, Dodie Bellamy and I talked about literary form, nineteenth-century novels, spiritual feminism, and reading through grief.

Sofia Samatar: Dear Dodie, I would like to ask you about paragraphs. Something I love about your writing, in fact something I’ve picked up from you, is a form I think of as blocks or boxes. Each paragraph is a block of text, surrounded by white space on all sides. These squares of text remind me of prose poems, or windows. What draws you to this form?

Dodie Bellamy: Sofia, Thanks for appreciating my paragraph blocks. The shape of them is important to me, and sometimes it’s been a struggle to get publishers to print them that way, a battle I’ve occasionally lost, but for the most part, when I’ve explain why I like them laid out that way — no indents, with extra space between paragraphs — publishers have been amenable to the layout.

So, why do I want this? Mostly my writing proceeds by means of accrual rather than a conventional narrative arc. Narrative happens, for sure, but in a more spastic way, appearing and disappearing throughout the text. So, paragraphs are simply placed next to one another, allowing them to resonate. I carefully arrange them, but on some level they’re modular.

And yes, I see each paragraph, in varying degrees, as a sort of prose poem. For some pieces I’ve written, each paragraph could be placed on a separate page, and it could be published as a book of poetry. But that suggests a preciousness that I resist.

I must have encountered this form for the first time in your novel The Letters of Mina Harker. I borrowed the book from a library back then — though now I have my own copy of the beautiful new Semiotext(e) edition! I remember being blown away by the boldness of these text boxes, which could take any size, shrinking or swelling to fit whatever you put in them. They could go on for pages in a delirious rush, or they could be brief and sharp, a single sentence. Is this form, with its startling rhythms, linked to the novel’s eroticism?

Creating a form where the reader doesn’t know what to expect and therefore can be startled, certainly is an sort of erotic play. That book is very much about excess, creating a style where it appears the narrator is stripped naked, so there’s an embarrassment that’s erotic. And also, there’s the issue of transgression. Of boundaries in general. But also social codes. The fact that in their original form each of those letters was sent to a living, breathing person, and they went places that I’d never say to a person to their face, created an intense erotic charge for me that hopefully comes through to the reader.

Absolutely. There’s such transgressive energy to Mina, and a lushness that seems to go back to that nineteenth-century Gothic potboiler, Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

Your new nonfiction collection, Bee Reaved, opens with an essay called “Hoarding as Écriture.” It’s about more things than I can list — among them grief, gelatin, symbiotic bacteria, all-you-can-eat buffets, and how you and your partner Kevin Killian placed your personal archives in the Beinecke Library. It’s also about Henry James: the epigraph is from The Ambassadors, and James shows up as a sympathetic figure, a kind of hero of excess, a writer who did “too much.” The Ambassadors is a very different book from Dracula, but both were published around the turn of the twentieth century. Do you have an affinity for books from that time?

Sofia, you have such an interesting mind. I love your pairing of Dracula and The Ambassadors. Dracula, too, is about excess on so many levels, including an excess of information. As Mina says in my novel, “I’m the one who gathered the notes, the journal entries, letters, ship logs, newsclippings, invoices, memoranda, asylum reports, telegrams — I transcribed them and ordered the morass so the Reader can move through it without getting lost.” To me, this prefigures the way we all write now in the midst of information dump.

Mostly I have an affinity for the 19th century novel, the sense of vast expanses of time, and all the attention to detail, which allows a luxuriously gradual intimacy to be established with a character. For instance, in Charlotte Bronte’s Villette, when Lucy breaks down, I don’t just observe her breakdown, I feel inside that breakdown; it’s as if I’m going through it with her. 19th century novels operate as brain cleansers from all the hyper fragmentation of the digital age. It’s hard at first to read one, like I have to be patient until my mind can make the necessary perceptual shift, and then I relax into a focus I feared I’d lost forever.

In terms of turn-of-the-century novels, I very much relate to Lea in Colette’s Chéri and The Last of Chéri. Though published in the 1920’s, the plots of the two books take place on either side of WWI. The war ushers in a new world that Lea, aging courtesan that she is, no longer has a place in. I resonate with the books because I too have straddled two very different centuries, and even though I’ve kept up with the new world better than many my age, there’s always in the background a sense of discomfort around the loss of paradigms I was born into.

I completely agree on the restorative pleasures of big old books! I’m currently rereading Proust’s giant novel — a book that, in terms of vast expanses of time and attention to detail, is the wild culmination of the nineteenth-century novel. Like Colette, Proust straddles two different centuries: writing in the twentieth century, obsessed with the nineteenth. And of course he was a huge fan of hers. I love the scene in Claudine Married where Claudine meets a young writer, who is obviously Proust, and he’s fawning over her and telling her she has the soul of Narcissus, full of sensuality and bitterness, and she’s like “Monsieur, you’re delirious! My soul is filled with nothing but red beans and bacon rinds!”

In some ways Bee Reaved is so much about the problem of finding a place in time. It’s infused with a sense of mortality, from the opening with the preparation of boxes for the archives to the concluding essays, so incredibly moving, that inhabit widowhood, mourning, and loss. One thing that happens along the way is the essay “The Endangered Unruly,” in which you turn toward the artist Mary Beth Edelson and the goddess-centered feminist spirituality of the 1970s. You mention that goddess culture was a huge influence on The Letters of Mina Harker, but you were too embarrassed to admit it when your novel was first published. But now you’re looking at second-wave spiritual feminists with sympathy and admiration: as if you would assure their place in time.

Love the red beans and bacon rinds! That mucking up of pretension. I have not read Claudine Married. I’m going to rush out and get a copy, for sure. Proust’s idealization of Colette makes me think of Kevin’s love and respect for fans. He longed to make a pilgrimage to Graceland because he saw it as a site of ultimate fandom. Sure he loved Elvis, but he loved what he saw as the selflessness of Elvis’s fans more. On the flip side, the fan’s idealism can lead to an extremism that can be scary if not dangerous. With the rise of social media, just about anybody can have a public image they lose control of.

As far as second-wave spiritual feminists, in the past few years I’ve noticed a return to many of their concerns. For instance, the experimental poetry scene that birthed me as a writer was so fucking intellectual and rational, I didn’t witness much room for magic there. And then suddenly all these witchy poets were doing tarot readings and talking about astrology. Like the second-wave feminists, they’re turning to systems that subvert Western logo-centrism; they’re looking for alternate origins. Of course gender politics have shifted, so current witchy types tend not to focus on unearthing an essential female essence.

All the crazy conspiracy theories that are virulent these days also present an alternative to the rational, or at least an alternative rationality. When I was writing my book The TV Sutras, in order to refamiliarize myself with the conversion experience, I watched hours of a YouTube series on sacred geometry, trying to drop my filter and allow myself to embrace what I was being taught. The series began with one dot, then two dots, then a line connecting the two dots, and within a few hours it was about how the Ark of the Covenant was used to build the pyramids, and I was totally there with them, even though I didn’t know what the Ark of the Covenant was.

Our post-truth world frightens me.

It’s terrifying. But as a writer, do you find magical systems attractive? I was just reading Ishmael Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo, and I was so drawn to the religion he invents in that novel, which almost seems real, or is it real? — composed of Vodun and Egyptian mythology and jazz. It totally convinced me while I was reading. And in fact I am still convinced by it as a theory of art!

Even if you don’t know what the Ark of the Covenant is, and you’re pretty sure you’re listening to some crank, a phrase like “the Ark of the Covenant was used to build the pyramids” is weirdly suggestive. It has a mythic force. Is there something about these eccentric systems that’s helpful for writing, even if you’re not writing directly about those ideas?

It’s interesting you mention Ishmael Reed. Mumbo Jumbo and Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down were important books for me in the 70s. I probably first encountered Reed in a grad English class I took, The Black Novel. The class began with Jean Toomer’s Cane and galloped forward in time. Reed’s books were popular among college students of my generation. I found his radical formal structures to be exhilarating. His fiction offered me a much needed vision of an avant-garde that wasn’t pretentious.

I’m also of the generation that was raised on Joseph Campbell and Carl Jung, so mythic structure was very much part of the conversation. Even before then, when I was a child I had a mass market paperback of Bulfinch’s Mythology that I read voraciously. The Greek pantheon had more of an impact on young me than fairy tales.

When I was an undergrad, Roland Barthes’s Mythologies was a game changer, his strategy of applying mythic structures to popular culture. Garbo’s face. Einstein’s Brain. I was so enamored of that book I couldn’t stand it. I would say that a primary concern of my writing is following Barthes’s lead of unearthing the myths we live in day to day. An example from Bee Reaved is the car chase material. The premise is that Kevin loved car chases in movies, while I found them profoundly boring, one of those many little irritations one has to endure when one is coupled. Then after his death I started looking at the aesthetics of chase scenes and thinking about what they meant to Kevin and to American movie viewers. As a metaphor they are so rich — total engagement in the moment, mortality, etc. Through the process of researching and thinking about them I became a total convert.

I realize your question was as much about magic as it was about myth. Yes to magic. I’ll take magic wherever I can find it. As a writer I’m always drawn to the irrational, and that’s where I always begin. Luckily I also have this anal part of my brain that will later kick in and organize and clarify things.

I love the part in that “Chase Scene” essay where you mention watching The Thief of Baghdad, and add: “I’m using every ounce of discipline not to write about it here.” I guess that’s the anal part of your brain kicking in, keeping the essay on track, but it doesn’t feel like discipline, as I read it. It feels like a glimpse of ardor. This type of intimate address is fairly central to New Narrative writing, from what I’ve read. But there’s an enormous generosity to it in Bee Reaved, especially in the second half of the book, in which you write about Kevin Killian and his death. The essay called “Bee Reaved” opens with a detail about the root of the Hebrew word for “widow,” which means “unable to speak.” How did you manage to speak in these essays?

How to speak of such loss is a central issue in the book. Also, when is it time to speak when one has no real grasp on one’s competencies, both in terms of writing and in terms of surviving. Joan Didion started writing The Year of Magical Thinking 10 months after her husband died. I wrote the first of the 3 Bee Reaved essays just a few weeks after Kevin died, in a state of numbness and shock. “Bee Reaved” was commissioned by the KW in Berlin for a catalogue to accompany an art exhibit they staged centering around Christina Ramberg. The Bee Reaved avatar — and the assignment to engage with images by Ramberg — created a sort of buffering between my grief and the page. I imagine that fiction provides a similar buffering in that the author can pour into the writing all sorts of personal vulnerability, but mask it with a sci-fi plot, or whatever.

The 3 Bee Reaved pieces were written over the course of a year and a half, and for each I tried to allow the essence of whatever relationship I was experiencing with Kevin’s death — at that particular time — to guide the tone. The first piece is about dissociation, and the second piece is about anger. In “Chase Scene,” the third piece, I chose an epistolary form in order to push myself into an intimacy, despite how terrifying that was. I don’t use writing as a therapeutic tool, but it often is, nevertheless. Before “Chase Scene,” it was too dangerous to connect to the love I shared with Kevin. After writing the piece, I’ve been able to allow that intimacy to emerge without it destroying me. I still cry sometimes, but I don’t think that’s a bad thing. The grief builds and the pressure of it needs to be released, right?

Yes. Bee Reaved gets at so many aspects of that process — the different tones of mourning, as you say. Recently, I attended your online conversation with Chris Kraus, and you mentioned the books you’d been reading over the past couple of years. It was an amazing list, a wealth of titles — a kind of grief syllabus. I remember it surprised me, but I was listening too hard to write it down. Would you be willing to mention some of those books?

Fortunately Chris gave me her questions ahead of time, and I was able to unearth my notes. What follows is a rundown of what I read, planned to read, failed to read.

Right after Kevin died, I voraciously read Joan Didion’s Year of Magical Thinking. After spending a horrifying week with him in the ICU, it would be a long time before I was ready to return to the land of the living. Didion presents a world I could recognize, relate to. I didn’t find her very good at interiority, but her focus on the details of her husband’s death, like almost fetishizing them, felt true to my experience.

I read Barthes’s Mourning Diary, or much of it — the fragment structure seemed perfect for an experience of trauma. Sometimes the entries felt like little pangs. My editor, Hedi El Kholti, sent me a passage from Proust in which a character says he thinks about his dead wife often, but only briefly each time. This felt true to my experience of grief. It’s like you cover your eyes with your hands and every once in a while peek out.

I read about after-death communications. I read about death by Covid, because Kevin died in a similar way, his lungs catastrophically filling up with fluids. What they called ground glass opacities on the endless x-rays. I read about brain tumors. I read the widowhood blog of Crescent Dragonwell, the vegetarian cookbook writer.

I read Prageeta Sharma’s poetry collection about the death of her first husband, Grief Sequence. Even though I didn’t know Prageeta well, she reached out and offered support and advice. She sent me an incredibly soft fuzzy blanket to wrap myself in when I needed comfort.

I read about dissociation. I read cheesy online stuff about grief and widowhood — there’s a whole industry. I read about Virgina Woolf and grief. Virginia Woolf comes up a lot when you’re researching grief.

I had a much more rigorous reading schedule planned, but I nibbled at it. I never got around to rereading To the Lighthouse. On my computer I found a pdf of Derrida’s Adieu, written in response to the death of Emmanuel Levinas. I know I didn’t read that. I was interested in books about women surviving alone under extreme circumstances. I planned to reread Christa Wolf’s Accident, and even though I could never manage that, I thought about the book so often it became a sort of talisman.

The most important thing I learned from my reading is that being okay should not be the widow’s goal; the pressure to be okay is due to fucked up cultural attitudes about grief.

I love this list. And the fuzzy blanket makes me think of reading as comfort, as shelter. It almost feels like we’re back to hoarding as écriture — only now it’s reading, rather than writing, that’s a form of collection or gathering. As if one could make a house of books.

This gives me a new perspective on your paragraph blocks. It’s a modular form, yes, and there’s an energy between the blocks, the way they’re placed next to each other. But there is also so much going on inside each one. Each block is crammed with experience, images, sensations, quotations, theories. I will probably think of them as overflowing boxes from now on — boxes of precious things, stuff you can’t bear to give up. It doesn’t make you okay, but it does make a kind of cobbled-together life. And life — that’s what your writing is to me.

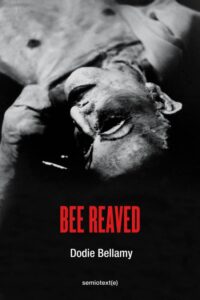

Bee Reaved

by Dodie Bellamy

Semiotext(e)

October 2021

Sofia Samatar is the author of four books, most recently Monster Portraits, a collaboration with her brother, the artist Del Samatar. Her work has received several honors, including the World Fantasy Award. Her memoir The White Mosque is forthcoming from Catapult Books in 2022.

This post may contain affiliate links.