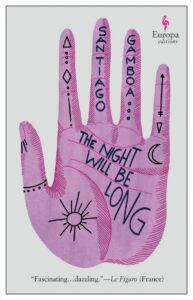

[Europa Editions; 2021]

Translated from the Spanish by Andrea Rosenberg

The Night Will Be Long is the fourth of Santiago Gamboa’s novels to be translated into English. The action of his first three spill out across countries and continents — his novels are generally transnational and global in scope. Necropolis (2009), set at a literary conference in Jerusalem, shifts between the perspective of characters from Italy, Colombia, and Miami, Florida. In Night Prayers (2012), unrest in Colombia creates instability that impacts Colombians in Thailand and Japan. Return to the Dark Valley (2017) is both a biography of Rimbaud and a sprawling noir that spans Spain, Argentina, Colombia, and Africa. As Gamboa’s characters traverse the globe, what remains constant is the perspective of at least one character from the author’s native Colombia. His newest novel focuses primarily on Colombia in the years after the 2016 peace agreement referendum between the Colombian government and Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC)).

Gamboa is master of demonstrating and exposing the paradoxes on which power thrives. In what seems a small, throwaway detail, a minor character relays a story told to him by his deceased son. The father, noting that his child was dishonest, says that his son was kicked out of the army for saving and then selling his ammunition. As an appeal, the son insisted that government higher-ups were sending soldiers into battle without ammo so they could sell the ammo for profit. Why, the father asked, would they send the people fighting their war into battle with no ammo? Because, the son explained, the powerful people never went into battle themselves, so it didn’t matter to them. Although the father doesn’t buy his son’s logic, the anecdote illustrates the insidiousness of trickle-down corruption.

The story begins when a young boy witnesses an explosion of extreme violence on a rural road near San Andrés de Pisimbalá, an area that was, for decades, FARC territory. The violent incident is unique, not only for its excessiveness, and the high-grade weaponry used: helicopters, bulletproof cars, grenade launchers, and machine guns, but especially because the conflict appears to have erupted between warring pastors and their bodyguards rather than guerillas and opposing forces. The novel follows three main characters: Julieta Lezama, a freelance reporter from Bogotá; Johana Triviño, Julieta’s secretary and collaborator, a Cali native who spent twelve years as a member of the FARC; and Edilson Justiñamuy, an Indigenous man from Ararcuara, Caquetá who works in the Office of the Prosecutor General in Bogotá. As all three characters set out to investigate the violence, they’re drawn deep into the world of evangelical churches.

In post-conflict Colombia, the new holy trinity is business, government, and religion. Evangelical churches have become massive corporations that exploit poor and middle-class workers to line the pockets of wealthy pastors, earn influence in business, and win protection from the government. Religious freedom is the best racket in town. Churches are vessels for money-laundering and operate outside the law.

Similarly, the novel shows the religious leaders that voted against the 2016 peace treaty later profited from massive government grants to help establish the same peace that they opposed. Gamboa’s post-conflict Colombia is filled with contradiction and a constant, ambient terror. The structures of violence are as incomprehensible as those of business and government, which, when combined with religion, work together to spread a conservative agenda to vulnerable people in the areas hit hardest by the conflict. Where a lesser writer would shy away and gesture towards the incomprehensibility of these powerful alliances, Gamboa inhabits multiple different voices to delve as far as possible into the inner workings of this corruption. He looks behind every closed door and never flinches. His characters travel throughout Colombia, cataloguing the sights of the highlands and lowlands, Cali and Bogotá, as well as Willemstad, Curaçao, and Cayenne, French Guiana. Information comes to us through diaries, emails, police reports, and an unnamed narrator that provides the perspective of our three main characters. We hear from pastors, parents of slain children and adults, gold miners, law enforcement, and more.

The modern world, as depicted by Gamboa, is both too connected and hopelessly fractured: immigrants from Venezuela beg for change on the streets of Colombian cities; Ukrainians vacation in the Colombian highlands; Colombians wear knockoff designer goods made in Paraguay; multinational corporations are situated in Panama, a “beach-fringed shopping mall,” but operated out of Colombia, Brazil, and French Guiana; business structures are inscrutable, and arranged as such to hide their criminality; the quickest flight from Colombia to French Guiana requires crossing the Atlantic Ocean, connecting in Paris, and crossing the Atlantic Ocean again in return; ex-FARC guerillas flee Colombia for Houston and other locales safe from paramilitaries; Colombians work as bodyguards for Brazilians looking to enact revenge on Colombian rivals.

Gamboa’s characters grapple with the fear that their country’s old battles will resurface while probing the way in which those conflicts take new forms. Although this new novel focuses on Colombia, Gamboa shows that the country’s conflicts are particular but not unique. There is the sense that similar quarrels are playing out in countries across the globe, and that the same actors: business, government, and religion, are responsible. People’s frequent inability to see beyond their own local conflict mirrors the novel’s sense that everything is both connected but fragmented. Human relationships are similarly afflicted. No matter how connected, whether by proximity or profession, the novel’s characters are consistently surprised by the peers with whom they spend the most time. Subtly, the question is raised: how well can people know each other? Will there always be some fracture?

Edilson Jutsiñamuy and his associates are consistently overwhelmed that every single crime seems to lead to another in a never-ending chain. Those towards the end of the chain, or the source of strife, find it easier to deny corruption, like the father who can’t believe his son’s story about going to war without bullets. Those who do get a glimpse of the truth, such as the son, are eliminated. That’s not to say that the novel is nihilistic, or without hope. The three main characters: Julieta, Johana, and Edilson are generally authentic, honest, and spend most of their time searching for truth and justice. They’re still complex, imperfect humans, though, and Gamboa leaves us, at the end of the novel, wondering after a major decision made by one of the three characters. Judgement is left in the hands of the reader. While this novel takes a hard look at Colombia’s secret alliances, the prose never turns towards the heavy-handed or didactic. As is typical of a Gamboa novel, the writing is beautiful yet straightforward; smart and literary but accessible; and always driven by thrilling, masterfully paced plots told through a cast of distinctive characters.

Patrick Duane lives in Gainesville, Florida where he attends the MFA program at the University of Florida and works as a creative writing teacher.

This post may contain affiliate links.