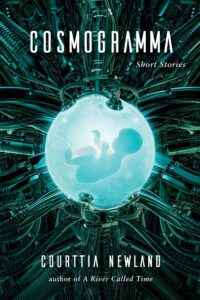

[Akashic Books; 2021]

Courttia Newland’s collection of fifteen short stories, Cosmogramma, reads like Black Mirror or The Twilight Zone turned into prose. Androids integrating into society, humanoid insects ruling the planet, and space travel technology allowing astronauts to explore black holes. Each world is stranger than the last. Each world power guides the choices of many, while others less fortunate are just trying to survive. Many of the protagonists need to make tough decisions about whether they want to endure or thrive. Newland presents an investigatory survey of people and places to make you wonder how you would react if the world were different. However, his speculation stops at the “what if,” often failing to present clear stakes or unpack the damage these universes may cause to individuals.

“Control” spans only a few hours. Young teen Danny is fed up with the ICO, an immigration enforcement agency. They have broken up his family and community. He saw these black figures come for his neighbors the previous night and watched as the youngest son in the family escaped from their house. He starts his paper route the following day and sees a billboard, “GO OR BE SENT.” Danny wanders around the city, remembering the pub his family tried to save but couldn’t and the ways the ICO has broken apart his family. We see everything Danny passes as he tries to evade the ICO on his route. Everything builds until Danny reaches his destination and makes a small choice with enormous consequences. Newland’s impressionistic scenes build tension in this near-future reality. Newland pans the narrator’s lens like a camera to take note of a character’s surroundings.

Cosmogramma is at its best when the stories are tight and fast-paced. This doesn’t only mean a smaller word count. “Seed” is one of three long stories, and I raced through it the fastest of all the stories. In “Seed,” strange purple seeds fall onto London front lawns one morning. At first, they seem innocent until they start growing into seedlings, then plants, taking the shape of the folks they’re around. When neighbors start disappearing, the protagonist Dapo must decide what he and his family will do to survive. The stakes could not be higher. As the plants slowly morph and stalk their prey, I anxiously waited for another victim to disappear. Newland paints a haunting picture with each scene. An artist, Dapo closely observes the sapling once it emerges from the mound. He takes stock of its shape, size, and the conditions surrounding it, as it grows in his garden. Dapo peers at the seed in each mutation, the purple shell now transformed and sprouting a face and body. In this story, Newland’s lens becomes a canvas with texture and drama to pull a reader through to the end.

At times, Newland overloads the reader with images, and the story sputters. The narrator spends so much time observing the views that the plot loses momentum. Alask is an augmented human and ringmaster to the Selarc Nation Circus in “Cirrostratus.” He has two extra ears on his forearms and a nose on his chest. His acts wow audiences now that these abnormal beings are no longer looked at with derision and fear. A close third narrator follows Alask, as he finds a new location for the circus, sets up shop, then spots a potential new act in a boy from the McClusky family on the first night and must convince the boy’s mom to let him join the show. At some point, Alask travels to the McClusky farm and says, “There was no hurry. The boy wasn’t going anywhere.” This describes the tone of the story too. The narrator takes his time to introduce each act and details the backstory of the circus, its ringmaster, and those of the McCluskys and the boy who might be a new act. Newland describes how a performer’s arm with an implanted fish tank inspired Alask’s journey with augmentation and changed his relationship with his mother. This foreshadows the moment Alask meets the McClusky boy and his mom. Yet, the tension of this scene fizzles out. There are no confrontations, violent altercations, or arguments that elucidate the ramifications of choosing circus life as an augmented person. In the end, I was entertained but could not take away any deeper meaning from my time here. Though I was dazzled and delighted by this most talented collection of folks, I became distracted that this story seemed to trail off before I could draw any conclusions.

Overall, I wanted to connect more to the characters as they navigated these situations. Feeling their emotions or understanding their motivations would have helped me engage with mystifying scenarios. For example, more connection with the protagonist would have made me far more invested in “Link.” Aaron has a traumatic sexual encounter with a woman who ensnares him in a dangerous organization. Still, I didn’t feel much expressed from him about the whole ordeal besides disorientation. Aaron is profiled, stalked, rendered unconscious, and kidnapped by masked energy masses. But there is no clear explanation or connection made between these acts and Aaron’s activism and voting preferences. Newland’s prose, even in “Scarecrow,” where he uses first-person narration, feels detached. Nicole and her boyfriend must evade armies of the zombie-like Sykes and Symps looking to cause havoc. The couple holds Nicole’s brother hostage in an isolated cabin as they wait to see which creature he turns into. These plot details should have made the story much more tense and eerie. Still, Nicole’s motivations and desires in this post-apocalyptic world are unclear. When her brother urinates on himself daily, she stops herself from reacting to cleaning him. She starkly describes her parent-in-laws’ deaths saying, “They’re dead, of course.” Nicole doesn’t reflect any emotion from her narration of the many traumatic moments in her new life. She lets her boyfriend deal with “what’s out there,” as she plays housewife and generally remains silent. It’s clear Nicole wants to keep her head down and stay exactly where they are. She has numbed herself, so I couldn’t engage with her as both narrator and protagonist. When she finally makes a decision about her brother, I didn’t feel its resonance.

Newland builds engaging societies full of unique characters and imaginative settings. They are stories with rich nouns and adjectives. These episodic jaunts focus on the difficult choices people make in desperate situations. But Newland doesn’t always bring the reader close enough to feel the reverberations of those decisions. Therefore, the stories remain so fantastical that readers lose sight of familiar actions and thoughts. Even when characters are nonhuman, I should connect to a level of selfishness, hopelessness, or courageousness of which we’re all capable.

Taylor Michael is an essayist and critic with writing in Artsy, Publishers Weekly, Full Stop, Hyperallergic, and ArtsWestchester. She is finishing an MFA at Columbia University School of the Arts and was the 2020 A Public Space Editorial Fellow.

This post may contain affiliate links.