[Dzanc Books; 2022]

I’m getting older; I just turned 30. Though I’m loaded with insurmountable student debt and would sell my soul for health insurance, though I’m a self-defined girl as opposed to a “strong woman,” and though the idea of checking in with any one individual about my whereabouts and emotions — let alone being subject to one’s every beck and call — makes me grind my teeth, I want desperately to be a mother.

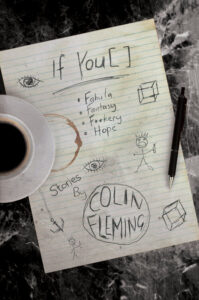

That’s what’s been on my mind as I read Colin Fleming’s short story collection, If You [ ]: Fabula, Fantasy, F**kery, Hope.

Maybe that’s why, of all the thirty-odd stories in Fleming’s new collection, the ones that I return to are the nostalgia-infused coming-of-age tales. Told from a first-person perspective, these three stories — “Yellow Hammers,” “A Deuce Cross,” and “One-Way Zebra” — read as the most “real” in the collection, nestled against paranoid vignettes of obsession, death, crime, and the afterlife relationship of Edgar Allen Poe and Abraham Lincoln that call their “reality” into question. These three stories are Wonder Years-esque. They have everything that signifies to me (a white, cis queer woman who came of age in the early aughts) the quintessential white straight male experience of youth and loss of innocence in some other, seemingly better, time. For instance, each of these stories are about a kid who will learn that people, himself included, are more complicated than he’d once imagined. Each of these stories features a girl who has the potential to betray our young hero and break his heart. All three churn with male friendship and the things that make males friends: sports and music, obviously.

When I read these stories, my brain purrs. Especially compared with some of the less narratively legible pieces in the collection, everything seems so normal. Absent dads have their stand ins: older brothers and friends’ dads, reliable but hands off coaches. Bones are broken, trust is broken, but gravity never falters. Even though bad things happen to the kids in the stories, things that would shatter a teenager’s life at least for a summer, I’m comforted by them, maybe because the worst things in the story are never happening to our young hero. They’re always happening to someone else.

Recently when asked by a friend if I could really imagine having children in This World™ I shrugged. I’m not convinced that This World™, despite the ever-present threat of climate change and the chokeholds of capitalism and the bigotry, is so much different from the world in which Fleming’s comfortingly nostalgic tales take place. Dangerous climate change has been observed by the scientific mainstream, if not the general public, since at least the 1970s, and to suggest that Fleming’s stories take place in a world not corrupted by capitalism et. al. would be to remove those things that make them comfortable and familiar, like baseball and Battle of the Bands and the Vietnam war. The main difference between these worlds and This World™ is that Fleming’s characters rarely if ever interact with This World’s™ ubiquitous screen. In “Yellow Hammers,” the kids listen to CDs, but they never torrent music or log into AIM. “One-Way Zebra” ends with a reference to texting, but up until the last page I was convinced that this story took place in a fabled ‘80s New England. Without the screens that would allow them to contextualize their lives in global catastrophe, the characters can experience their personal loss and growth as just that. Not subject to the distraction of a barrage of ads or worldwide reactions to the internet’s main character of the day. Subject instead to the ways their loss and their response to that loss effect those closest to them. Personal.

“Things were just as bad when our parents decided to have us,” I defended myself to my friend. “It just wasn’t as obvious to them.” Then I scrolled through my Twitter feed on my iPhone, where I found a link to an article in Harper’s about social media content houses during the COVID-19 lockdown, where kids (ones who meet a certain standard) have the chance to “come of age” while millions of other kids watch, and get paid big bucks to do it. Tiktok is just baseball for Gen Z, I soothed myself. But who am I kidding? All nostalgia is fantasy, just like all literary realism is fantasy: both constructed around gender and class norms to represent worlds where things happen in a more or less predictable manner, however painful they may be to witness or experience. Say I were to have a kid nine months from now. In 2041, would they look through TikTok archives, using whatever device has become ubiquitous by then, and feel that pleasant purr in their brains, recalling a predictable, stable time they were born too late — or in the wrong place or with the wrong parents — to know?

These three aren’t the only stories told from the first person, with more or less checked absurdity. “My Death Tie” is a morose and panicky Trojan horse of stories packed into stories packed into five and a half pages, but nothing in it is unbelievable, per se. In “Analogues,” where a man waits for his wife’s mother to die, Fleming deftly describes waiting room paralysis. And his story about a man who, instead of meeting up with the yogi he first met on a dating app, engages in light stalking and imagines hallucinating a demon while failing to move on from his ex-wife, “Red Sweatpants,” is depressing and all the more disturbing for its believability. This must be what the kids in my three favorite stories grew into, after their loss of innocence and impressive junior league sports careers.

In what seems like a deliberate move to highlight an inability to connect meaningfully with the world around them, none of the characters in Fleming’s stories have children of their own. Even Abe’s ghost never mentions his offspring, though assumedly his kids would also haunt the immortal plane. The waiting room lock-in that has trapped the narrator in “Analagous” is precipitated by his and his wife’s explicit choice to not have a child. What many of the characters do have, though, is parents. Many of the grown men that tell us their stories in Fleming’s collection see themselves, and those around them, first and foremost as somebody’s child.

Take the narrator of “Rimer’s Boots,” which comes at the end of the collection, a last nostalgic tidal wave before two surreal splashes finish us out. In 1968, Clark, a Korean war vet from Boston who has worked his way across the country with odd jobs, finds himself caught up with Rimer, a San Francisco music bootlegger who calls himself an artist but might be an angel or a demon. We understand Clark through his own eyes as afraid of the past and pessimistic, if curious, about the future. He checks his new life against his old life through the internal perspective of his parents, who always disapprove, particularly of the music Rimer bootlegs — “come now, son, wouldn’t you prefer some Brahms,” he imagines them saying. But no recording of Brahms’ has the power that Rimer’s bootlegs have, the time-stopping quality, the uncanny ability to make listeners feel like they are sitting directly inside of the musician’s head but also in the most significant moment in their own life. “Music isn’t music if it doesn’t transport you somewhere inside yourself,” Rimer says.

Eventually Viacheslav, Rimer’s most persistent customer, and also his antagonist, nemesis even, fills the father role in Clark’s life, even though if anyone is absent from his family, it’s Clark himself. Unlike Clark’s calm father, who can peel an orange all in one piece, Viacheslav is an “old guy, alone like that . . . having to look at what had been, and what he wanted to be, and seeing that nothing measured up.” And yet, Clark seems to see Viacheslav as a moral compass, a man who is self-aware enough to know that his indulgences oppose his intentions, and humble enough not to act otherwise. Or perhaps Viacheslav is merely a compass pointing towards the future. “I was on my way there myself.”

Throughout the story, in a dazzling display of arrested development, Clark never stops to consider his own effect on the people around him and the world that occupies him, beyond his involvement in producing the recordings. The only way he understands himself to be capable of effect is through the recordings, which affect everyone, and then there’s everyone else, who all affect him. But he does shake his aimlessness and embrace his past and his potential, under the influence of Rimer’s otherworldly recordings and Viacheslav’s cryptic guidance. He returns to his family home, where he grows at least enough to recount this story.

I’m critical of Clark, but it’s hard not to see myself in him. My own arrested development is difficult to reconcile with my desire to have children. I envy the children in my favorite stories, and identify with Fleming’s childless deviants like Clark and Rimer. If bound up in the responsibilities of domesticity, how would Clark have even made his way to San Francisco? And in Rimer’s case, the art would certainly suffer. He would never be able to spend his nights crawling through concerts to record his otherworldly bootlegs, stashing his car in alleyways, hiding from customs, if he had a couple of kids waiting at home. I can’t fathom providing the kind of childhood I would want to provide, where life is as predictable as gravity, because I can’t fathom myself as predictable. But I challenge the notion that my unpredictability is innate to my identity, a trait that necessarily correlates with the life of an artist. Rather, and Fleming seems to suggest this with his isolated characters who wander through their lives in states of panic and fugue, my unpredictability is as systemic in its origin as climate change, a response to the persistent difficulties inherent in This World™. Though musicians are wary of Rimer’s uncanny recordings, it’s his attempts to avoid law enforcement (ultimately working in favor of commercial interests) that lead him to behave erratically.

On one page of his collection, Fleming captures a version of this world, in his nostalgia-laced stories, that makes me long for something I’ll never get, like a New England t-ball childhood or the chance to listen to Rimer’s bootleg recordings. And on another page, Fleming shows the stark reality of This World™, with characters compressed by their loneliness into underdeveloped packets of needy desire. I look for the Hope referred to in the title, but instead I see myself: distracted by the Fabula, desperate for the Fantasy, drowning in the Fuckery. But there’s more to me. There’s yearning — not just the hungry, mindless desire of commercialism, but the willful want for something different. Something more. I want to have a family. And how could I want that, without Hope?

Hannah Lamb-Vines reads and writes in New York City, northern California, and the Texas panhandle, depending on the time of year. Her work has recently been featured or is forthcoming in Columbia Journal, HAD, and Black Telephone Magazine, among others.

This post may contain affiliate links.