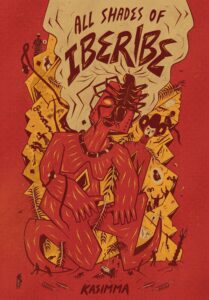

During my initial reading of All Shades of Iberibe [Sandorf Passage, 2021], the debut short story collection of Nigerian writer Kasimma, I found myself having an uncanny experience. I was certain I’d read her story “Where One Falls Is Where Their God Pushed Them Down” somewhere, despite not being familiar with Kasimma’s work prior to reading All Shades and unable to say which journal had published the story. A quick check of the copyright page disconfirmed my initial feelings. Still, the impression that I’d read the story before lingered. As Kasimma spoke to me over Zoom, the idea of unconscious resonance became a primary point of our conversation: it not only informs Kasimma’s process as a writer, but speaks to a central feature of the tensions in her stories. Family betrayal, small-and large-scale displacements, bodily violation, skewering of beliefs — all these are charged with the aftereffects of modern strife like the Biafran War, the lingering damage wrought by colonialism, and even conflicts set in Nigeria’s antiquity. Ghosts abound, and almost everything is as the collection’s title says it is: iberibe, messed up. At the same time, Kasimma’s stories are cumulatively interrogating the way that the world is informed by language. The meaning behind a name, the definition of an idea, the words exchanged between two lovers — they shape the contours of reality for her characters, just as they do for us in our lives, for better or worse. And so, as Kasimma discussed with me near the end of our call, it is a shift in language — that is to say, a reimagining of the kind of stories we tell — that create the small openings, allowing change to slip in and mold a new world. This is the possibility her stories hint at despite their darker dimensions, a testament to the quality of this collection and the skill of its writer.

During my initial reading of All Shades of Iberibe [Sandorf Passage, 2021], the debut short story collection of Nigerian writer Kasimma, I found myself having an uncanny experience. I was certain I’d read her story “Where One Falls Is Where Their God Pushed Them Down” somewhere, despite not being familiar with Kasimma’s work prior to reading All Shades and unable to say which journal had published the story. A quick check of the copyright page disconfirmed my initial feelings. Still, the impression that I’d read the story before lingered. As Kasimma spoke to me over Zoom, the idea of unconscious resonance became a primary point of our conversation: it not only informs Kasimma’s process as a writer, but speaks to a central feature of the tensions in her stories. Family betrayal, small-and large-scale displacements, bodily violation, skewering of beliefs — all these are charged with the aftereffects of modern strife like the Biafran War, the lingering damage wrought by colonialism, and even conflicts set in Nigeria’s antiquity. Ghosts abound, and almost everything is as the collection’s title says it is: iberibe, messed up. At the same time, Kasimma’s stories are cumulatively interrogating the way that the world is informed by language. The meaning behind a name, the definition of an idea, the words exchanged between two lovers — they shape the contours of reality for her characters, just as they do for us in our lives, for better or worse. And so, as Kasimma discussed with me near the end of our call, it is a shift in language — that is to say, a reimagining of the kind of stories we tell — that create the small openings, allowing change to slip in and mold a new world. This is the possibility her stories hint at despite their darker dimensions, a testament to the quality of this collection and the skill of its writer.

Joseph Demes: To start, I wanted to know what the genesis of the collection was: how long ago did you start writing these stories, where in the collection did it begin. Basically, I’m curious to know which story feels to you like the anchoring point of the collection.

Kasimma: That’s a difficult question… I didn’t write them with the intention of having a collection. I had all these stories, and then I began collecting them. But I think the oldest story in that collection is “Life of His Wife.”

Which is the shortest story too!

Yes!

It’s also the most overtly funny story and one that really challenges the reader to read tone to understand the solid relationship between the couple. And I find that interesting because it seems to me that one of the major concerns of the book is a question of stability: many of the characters not only struggle with the challenges of life in their respective eras, but reconciling the lack of stability that foundational values and touchstones in their culture supposedly offer. Family, for example, doesn’t provide that. I’m thinking of “Ogbanje,” “Where One Falls is Where Their God Pushed Them Down,” and especially “All Shades of Senselessness” — there are major betrayals by family members from the get-go. So “Life of His Wife” is great because this couple’s whole dynamic is built on playing at betrayal, but from a place of trust that builds upon itself. Was that something you were thinking of in the writing process or did it emerge later on?

I think that just happened. I didn’t write the stories with the intention of having a theme come together. But “Life of His Wife,” as I said, is the oldest story, and I was really playing with what marital life is like. The funny thing is when my editor, Buzz Poole, and I were working on the collection, we had to remove some stories and add others, and so I suggested taking out “Life of His Wife” because it’s the oldest and, as you rightfully said, it’s funnier than the other stories. I felt it did not belong here. My editor said, “No, it needs to be in here, so that in the midst of these heavy themes, there’s something tender.” And that’s also why it’s placed where it is, which is almost in the middle of the book. So it’s like, you read all these in the first half, you have a drink of water here, and then you continue.

Which is perfect placement. I think the rest of your stories have their funny moments, they’re just not funny. Obviously. [We both laugh.] “Jesus’ Yard” sets up quite a lot of moments of situational humor. Chinelo, the main character, is really not on the same page as everyone else: she struggles to read the room or understand why someone is saying what they’re saying, whether in Igbo or English. When you’re writing, do you prioritize one language and then translate into the other?

English is the language I know how to read and write best. I don’t know how to read Igbo very well. English is the official language in Nigeria. It is the language of instruction in our schools. But I salted the collection with Igbo because it is my language, and I’m very proud of it. I feel Igbo has been pushed to the side — and not just Igbo, really, but most native Nigerian languages. We have more than 250 languages in Nigeria. Igbo has different dialects too. Someone might be speaking Igbo, and I would not understand a word. All these rich languages have been shifted to the side because we have to speak the language of the colonizer. It’s the “founders” of Nigeria, the “fathers” of Nigeria, that compelled us to, and now, most of these languages have died. If something is not done, my language might tick that box. So this is me finding a way to keep this language alive. If in the next 100 years it is dead, then hopefully someone will read my book and read the books of other Igbo people and know there was a time when this language existed.

Certainly. I asked mainly because it’s one of the main questions of how a translation operates: is it trying to bring a sense of familiarity to another language that might make things more accessible for the reader, or does it make the reader work to understand another language, and with it another culture, on its own terms? Not knowing how it was written, I felt that All Shades was working by the latter principle but that it was also teaching me as it went. There were clear nodes, whether they were moments that helped place the story historically or on the sentence level — how parts of speech in Igbo operated depending on the context — that I could get a hold of and use to read further into the stories. Making those decisions puts extra work on the writer; how much did that affect the pace of your writing?

It did not. There are some stories in the collection that I wrote in one sitting, within hours, and then others took me days or weeks, depending on how the spirit leads. I can say that “Caked Memories” was the most difficult to write. I wrote the first version and felt something was wrong, and wrote a second version, a third, a fourth. “Mbuze” took the longest time to edit. [Laughs] My editor and I kept going back and forth on that story for I-don’t-know-how-long. It took time before we settled on the direction of “Mbuze.” But then other stories were quite easy like “This Man.” I wrote that one in one night. “Coffee Addict” was also a bit easy. I wrote that in just a few days. “My ‘Late’ Grandfather” I also wrote in one sitting. The thing is, I write very fast. I can write a story in a sitting from beginning to end, and then I leave it for a while, and come back to it later. Apart from “Life of His Wife,” I wrote every other story in the collection from January to December of 2020 and sent it out to my editor this year.

And your process has always been that quick?

Yes, I write very fast. [Laughs]

That’s amazing. I’m jealous. Along those lines, I will say I kept coming back to “Coffee Addict” because it seemed to be very much about the writing process and grappling with this struggle to understand what, as a writer, we’re looking for when mining through the past, whether that’s our personal history or a collective one, for our stories. And how when we go through these things they often bring up difficult questions about ourselves or the place we live in, things we may not want to acknowledge. I’m thinking of when the main character, Mgbeke, is confronted by another character, The Woman, who’s kind of a version of her grandmother or a meta-character that Mgbeke is talking to — when The Woman accuses her of being a misandrist because the only men she reads are her friends. And likewise, Mgbeke pushes back against The Woman’s denial of lesbian relationships in Nigeria.

You know, I hadn’t intended to write that story the night I wrote it. I was awake and, I don’t know, reading or something else. But I drink coffee a lot. [Laughs] So I was getting myself a cup and when I opened the coffee container and the scent of coffee . . . [inhales]. For a few minutes I was just there, holding the container, inhaling the scent, receiving the satisfaction as if I had just drunk a cup. And I wondered, what if I had a character who loved coffee but, in the story, never drank it, only took in the scent. All I had was the first line and the name, Mgbeke. So I just opened a fresh document, and I typed the first line of the story. I assumed, in my head, that it would be just a reminder of a character I wanted to write about. And I’m surprised the title stayed, even that first line, which ended up as the last line of the story, stayed too. I came back to it days later and still didn’t have an idea of what to write. But I said, “Let’s try a second line.” So I wrote one, describing where she was. As I said before, I write very fast, but when I write I listen very attentively to my characters. I just listen. Sometimes I stop typing and listen. I keep quiet and I listen. And they talk; I hear them. I’m just the one writing. I’m not the owner of the stories. So I heard her voice. I heard her saying, “This is who I am; this is why I came here,” and I continued writing until I was done with the story.

The part about The Woman insisting that marriage between two women is not gay marriage: over sixty years ago in Nigeria you could not come out as gay — you just could not. Even now, you can’t really come out. Someone might try to stone you or kill you. So I was trying to compare how, in this woman’s age you didn’t have this term, gay marriage, and yet women were marrying women. Even now, in Igboland, it’s still allowed in some circumstances. Though a man cannot marry a man. Till today Igbo people say, when women marry women, “They are not lesbians.” Then what is it? [Laughs] In the story, I had these two women arguing — one from our age, Mgbeke, and one from the gone days, The Woman — about what to call it. Even today it’s just called “woman-to-woman marriage.” I guess sixty years ago they really had no single English name for it, but now we have one and we know what it is, and still there is that pushback. People say it’s just a tradition. No, call it its rightful name — don’t say, “It’s just a tradition.” Don’t hide it behind that. Talking about being a feminist or being a misandrist, I wanted to push a similar point: that not everyone who says they are feminist is a feminist. Because I think feminism is not about hating men. There are people who visibly and orally hate men and justify this under the umbrella of feminism. Mgbeke has issues with men: she doesn’t want to get married, for good reason, but she has taken it so far that she won’t read male authors. And so for her grandmother to put it to her repeatedly that you’re not a feminist, you’re not, this is all to say: tell it as it is. You don’t have to call yourself something you’re not.

Which is a major internal dilemma a lot of your characters come up against: trying to live up to an identity but behaving otherwise. I see it in the basic internal conflict of the main character in “Worthless Strength,” Ikeemewuihe, this young man struggling to live up to the more nuanced meaning of his name, “strength is not the answer,” when he’s constantly having to fight and steal and trick people in order to survive — having to demonstrate “worthless strength,” the less nuanced meaning of his name, all the time. And then he becomes the president, which raises the larger question of what it means to have power, and to use power to its better end. Politicians the world around are a prime example of people who fail to do just that.

Nigeria has not been so lucky with leadership. The major problem the country has is her leaders. I don’t understand how, from our independence until now, from military rule to democratic government, we still have the same issue: bad leaders. I tried to capture that in the collection. In “Worthless Strength,” Ikeemewuihe comes from nothing, everyone calls him a bastard, and he’s seen as this ne’er-do-well. Then he becomes the president of the country. On the one hand, it’s a way of saying, “Anything is possible, no matter where you come from or what your story is,” which is what his mother had been trying to tell him. At the same time, he keeps feeling like, “Oh, I don’t have an education, I can’t be this.” Well, how many of our politicians really did have an education? Still, based on his qualifications in the narrative, Ikeemewuihe really should not be president. And this is how it is: we keep giving the office to people who aren’t qualified. This story is poking its fingers at Nigeria’s leaders, saying, “You know you’re not supposed to be there.”

It’s also what “Shit Faces” deals with. You have this king who is quite diplomatic, clearly qualified to be a leader, trying to essentially dissolve a caste system and who tries to show kindness to one particular outcast, Nnemeka. And by the end of that story, it’s teased out that even the most qualified leaders are kind of unfit for the positions they hold because the things they’re trying to uphold, like justice, are actually really slippery. And then it’s a question of what gets in the way of doing just that, which “This Man” gives a sort of answer to.

Well, I don’t know about “unfit.” He’s king by birthright; that qualifies him in a certain aspect. But he’s not trying to please anyone or prove anything to anyone; he’s just trying to be fair and just. Now, in “Worthless Strength,” Ikeemewuihe is someone who in the future might have gotten an education. In the story, however, we don’t know what he did or didn’t do for the country — so we can’t judge him on that. But there are people who do not have the qualifications to be president and who then end up holding power. Granted, some of them may have the intention to do something good for the country, but it’s really not possible for them to be fair and just because of the way they got into office in the first place: through corruption. Anyone who ends up in power by fair and just means will not be afraid to dispense justice. In Nigeria, someone can be tried simply for being gay and sentenced to 14 years in prison. There are some people applauding this and some people who oppose it. And what you do as a leader, who you support, has a lot to do with how you came into power. So, the king in “Shit Faces” is confronted by his friends saying, “Oh, you can’t do this, you can’t extend a hand of friendship to Nnemeka.” But he’s rightfully king; he can do whatever he wants. No one’s going to tell him, “You know you’re not supposed to be king.”

No, you’re right. Let me rephrase what I said: even though the king in “Shit Faces” has a much clearer internal sense of justice, he still hesitates to act it out one-on-one. Even when he’s in Nnemeka’s home, he is reluctant to accept them as an equal. You see it in his body language, in the way he clearly feels uncomfortable and is always suggesting they move and talk elsewhere. It’s this fundamental human inability to really enact the responsibilities of office or leadership. And the concept of “This Man” provides a really clever quote-unquote explanation of why things are the way they are.

You’re absolutely correct. I also believe that the solution to any problem is a problem in itself. The narrators in “This Man” are saying at the end, “If you do not bury us properly, we will keep negatively influencing leaders’ decisions.” That is, as you rightly said, explaining why things are the way they are. But doing what these spirits want does not necessarily ensure that the country would get better. Now, you have to understand: burying someone properly in Igboland is a big deal. It’s like — well, I don’t know how much time you have to delve into this.

[Laughs] I have plenty of time; I would love to know more.

[Laughs] Ok, then this is it: I wrote that story in one night, and I don’t know what I was doing before I started writing, but the urge to write was strong. It was compelling and stubborn, like “Write now. Write. Now!” It didn’t give me any chance to say no. And it was not one voice; unlike “Coffee Addict,” which was just Mgbeke’s voice. This was plural, the first voice I’d ever heard in plural: we this, we that. I did not stop until I finished that story, and I came out exhausted. This story didn’t go through many edits. If you’ve read Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun, you would remember that Kainene, towards the end of the book, goes missing and is never found. It was something like that I was hoping to capture in “This Man” — in the edits after I’d written it. There are people in Igboland till today — and I think it should be more than forty years since the war, maybe fifty years now — people in Igboland who are still waiting on their loved ones to come back. And just as in the story “My ‘Late’ Grandfather,” where someone is mistakenly buried, there’s a ritual that has to be undergone to bring the person’s spirit back. We believe that Ala, the goddess of the earth — and in Igbo, “ala” is the word for “land” — cannot just give back what has been given to her. You have to replace it with something if you want to take it out. So people who are waiting on loved ones to come back, they don’t want to hold a funeral for them because they don’t want to bury them in error and have to go through the process of taking their spirits back.

Now, most of these missing people are dead. And because they’ve not been properly buried, we believe they cannot cross into the afterlife. After I sent out the manuscript, I started researching — I got hungry to know more about Igbo culture, tradition, religion. So I started reading and reading, and you can imagine my shock when I found out that these things I wrote, thinking it was entirely fiction, are beliefs that actually exist. We’d finished the manuscript at that point, actually, and done all the editing when I started researching. I found that those spirits exist in Igbo ontology. They have a name: ndi ọgbọ na-uke. These are spirits who cannot cross over and are stuck between two realms. They will keep causing havoc until they are properly buried. And they need blood to cross over to the other side. There is something called iwa anya, which means “opening the eyes of the dead.” It’s done with blood. Before a spirit can cross to the spirit world, to Be mmụọ, blood must be spilled. It can be the blood of a dog, of a cock, of a goat, but an animal must be slaughtered to open the door for them from this world to the next. It opens their eyes, makes the path to the afterlife clear to them. So when they are not properly buried, they are just stuck between worlds, and what do they do? They get angry. The solution to the problem is to simply kill this animal. Just kill an animal let them leave you and go. And until this happens they will just keep wreaking havoc. Doing this is not the only solution to Nigeria’s problem, but it’s a start. I did not know their significance when I wrote them. So you can imagine, it was a bit scary!

I can! I had a slightly similar, less frightening experience when I was reading “When One Falls is Where Their God Pushed Them Down.” Midway through I stopped and was trying to remember if I’d read it somewhere; there was a strong sense I’d come across it online or in a journal. So I checked the acknowledgement and saw the story hadn’t previously been published, but I had the distinct feeling that no, I’ve read this story somewhere before, even though clearly I hadn’t and your collection had been recommended to me only a few months ago. It was a very uncanny feeling, to think that I was suddenly re-experiencing what I was reading, that it was just me reencountering your work. I think that’s just the sign of very good writing, the feeling that you’ve read it before somewhere even if you know you haven’t. But that’s just wild to know that in the process there was also this real one to one correlation of what you wrote and the reality of the traditions and beliefs that you weren’t aware of before you began writing.

[Laughs] It is. I don’t know how many stories in the collection mention spirits off the top of my head!

At least half. [We both laugh]

For goodness sake! I just hope that it’s my imagination! I can’t deal with spirits finding their way to where I am. Living with fellow humans is already a lot; I can’t have spirits coming in too. But really, I feel like every writer should listen to their character because that character came to you for a reason. I’m not the only writer in this world, I’m not the best writer in this world, but for a character to come to me, it chose me for a reason. And I have to do justice to their story. Someone was talking to me about the book and they said how they liked that I don’t impose anything on my characters; I just let them be. And I said, “Well, it’s not my story! I’m just the vessel.” The story’s being told through me. And I feel that’s the best way to write a story: to just listen. Even if it doesn’t fit the norm, or what you think will sell, just write the story first before bothering yourself with whether or not the story will sell. Write it first and then think about that later.

I agree completely with that, we do have to listen to what the character or what the story is trying to do rather than what we want it to do. But it’s difficult. At least in the US, the professionalization of writing through MFAs and through sort of like the real ingrained practices of the publishing world make that very difficult, because so much of the time when you are trying to write, the last thing you’re thinking about is the story itself. You’re thinking: how will it fit into this yet-to-be-finished collection? Who is my target audience? Who is the agent I want to represent me? What’s my ideal press or journal to have this published with? And those are all important things to think about later, down on the line, as you said. But it is very difficult to cultivate that practice of quietness and listening to the inclination of your characters and your stories because there’s a lot of noise going on. Do you have a sense of when that intuition really came about, at what point you realized: this is what I have to do, it’s not about me, it’s about the story.

Yes, I do. I’m fortunate to belong to a tradition of great writers, world-acclaimed writers, by being Igbo, being Nigerian. So, being under that umbrella kind of gave me permission to be myself. I started writing at a very young age, yes, but I went through this phase of writing what I thought people wanted to read: writing stories that would mirror the kind of things I’d read. And I’d grown up reading Cinderella, Little Red Riding Hood, Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, all those stories. And all those characters were not me, not anybody in my class — they were people who had no business with udara. I copied them. And then as I grew up I started reading Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Flora Nwapa, Cyprain Ekwensi. I started seeing something different: people like me inside these books, people who eat eba, who speak Igbo. And I was like, Ok, it is possible to write like this. And then I started reading Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, started reading Uwem Akpan, Chika Unigwe, EC Osondu, Okey Ndibe, Chigozie Obioma. But basically, reading Americanah and Purple Hibiscus especially did it for me. Then I attended Chimamanda’s workshop and that was when I told myself, “Yeah, you’re allowed to do this. If she says it’s ok, it’s ok.” [Laughs] Because she taught us to write from the heart first, then think of what inspired that later. Since I adhered to that, I started selling stories. Before that, I was always thinking, “Who is my target audience? Who am I writing for? Will they understand me?” I didn’t use Igbo words in any of my stories. So I came out of Chimamanda’s workshop in 2019; I started writing and placing stories in 2020; I had the collection finished and picked up in 2021. It taught me: it’s ok, listen to her, she’s right. It’s ok to write what comes to you. Lola Shoneyin taught me to write as it sounds to you, in your head; don’t think about writing beautiful sentences, just write it first and then you can start talking about beautifying sentences. So, hearing all that — thinking about where you’re going to send your story before you write, as if you have to mirror your story to what that journal publishes before you write it — that all still seems strange to me. I don’t do that. I write my stories, and I send them out, and if you don’t want it, biko give me back my story and let me send it somewhere else. [We both laugh] I’ve sent stories to journals who’ve said “Oh, this isn’t what we’re looking for, but should you change this or add this, we can maybe keep it for the next issue.” The most important thing to me is listening to my character and that has worked well for me. I think I’ll continue doing what works for me. [Laughs]

You should! And I agree. It’s very difficult, I think, to consistently do that because oftentimes the character’s voice is very quiet. And the world really seems to seep in so aggressively to our writing practices, as you and I have said, and it’s difficult to push it away. I don’t know if you like or don’t like to speak about projects while they’re in progress — this question can really interfere with the writing, so don’t answer it if you don’t want to — but what are you working on now? And what are you reading right now?

I want to write a novel next. I’m not so sure what it is, but that’s the next thing for me. And not because I already have a story collection but because I have an idea of what the novel should sound like. So it’s just getting it straight — or just listening, waiting for it to talk when it’s ready to talk. And I just finished reading Visible Empire, by Hannah Pittard. It’s interesting how it’s grappling with forgiveness. So the main character, she’s pregnant, and her husband was having an affair, and his mistress died in this plane crash which actually happened in 1962, in Paris. Hundreds of people from Atlanta died. And he’s so heartbroken because his mistress is dead. He leaves his pregnant wife. So it’s them coming to terms with this, her forgiving him. And I found it very interesting that forgiveness can work in different ways — that it’s possible to forgive irrespective of what someone’s done, but to let that person back in can still be difficult.

That makes sense, because that’s another big concern of the collection: how to accept the senselessness of what happens in life, or the senseless things people do to us, and move through it. That’s exactly the struggle in “Virgin Ronke” this question of how you continue after a major violation like rape. And especially in the context of the story, where Ronke is being forced to prove her virginity, and is constrained again by what’s happened to her and what the culture expects of her. And then the doubling of everything she’s feeling with her father-in-law conducting this test to see if she’s still a virgin — she calls that the real violation, walks away from her family and fiancé who’ve pushed her into this corner. It’s a question of how you continue to live when you’ve endured things that are difficult to live through, and with, and speak about — or are not spoken of. And this extends broadly to thinking about major conflicts in Nigeria’s history — war, genocide, colonialism — from all of these large-scale conflicts that also play out on the individual level, in the sort of devastating ways that make it, whether it’s materially or psychologically, impossible to move on to or from.

You’re right. Because most of the characters have trouble with this question of “How do I continue to be?” Especially in “All Shades of Senselessness.” Even me, I wrote the story, yet I don’t know what I would have done were it me. When we were talking about what the title of that story should be, we initially wanted it to be “All Shades of Iberibe,” to have the title of the collection nestled in there. But then later we decided, “No, let’s use the English phrase, ‘messed up.’” And at the dying minute, I said, “No, change it to ‘senselessness.’” Because it is senseless; I don’t understand what kind of tradition that is. There and in “Virgin Ronke” both characters are almost facing the same thing: these senseless practices. They have been wronged by their families who would not admit their wrongdoing. Without forgiveness, how can these characters move forward? And “This Man,” given the Biafran War, is also asking the question: what do we do next? Earlier, I said that the solution to the problem might also be a problem: performing burial rites for these missing people might not actually solve everything. It will be a start, but it does not guarantee things will change. When I was in secondary school in Nigeria, we were not taught about the Biafran War. It’s scrubbed from the curriculum. They teach about British colonization, but not the Biafran War. Why? Because they believe erasing it would somehow make it that maybe in the next 100 years nobody will remember that it happened, and then we’ll all live happily ever after. That’s just not true. Not acknowledging the problem can never be a solution. Visible Empire is interesting because there is that acknowledgment between the couple, “This is what our problems are. How do we move forward?” The first step in moving forward is acknowledging that something bad has been done: someone has been wronged or offended, how did we wrong or offend them? So we cannot tell those who were wronged by the Biafran War that nothing happened: people were massacred. And that’s why Rwanda is moving forward: they acknowledged the genocide. But Nigeria, my dear Nigeria, pretending that no Igbo person was killed, that those pictures we saw were not true — it’s not going to work. Without acknowledgement, I don’t think forgiveness is possible.

We have a similar problem in the United States, and it does not seem like it will abate any time soon. It doesn’t seem, at least right now, that we are on the right track to admitting and repairing and moving through long-standing injustices in our history.

I do really believe in the power of stories to change things though. I really do. I said earlier that I grew up reading Cinderella, especially. We read fairy tales where, in most of the stories, women were the villains. Hansel and Gretel, Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella — it was always a woman causing problems, and it was always the men solving problems. And there was a time in Nigeria when being a stepmother automatically made you seen as a kind of devil, because of these stories. It took telling different stories to change this narrative. It all depends on what story you’re telling. So it may be a minute step, but still, if someone reads my work and says, “Maybe we should conduct a funeral for those missing people,” it may not have gotten to the whole, but I’ve gotten to one person and that’s a step. People remember the stories they’ve been told. Cinderella has been around how many years now? But it’s around because people keep passing it on, passing it on. If writers use stories to correct some of these ills, making peace with it in their characters, maybe one day these will be the stories we know. Maybe one day, coming up to the table and actually discussing issues, accepting what has gone wrong, and looking for a solution will be the norm. And maybe this will happen because of stories that have been told where these things have happened. I am hopeful that the world my children will meet when they become adults would be better than the one I’m in right now, and the one their children will grow up in will be even better. And by the time I come back to this world, I believe I will be coming back to a better world.

I think the same way it takes quiet to write your stories — to be quiet and listen to the characters — it’s a question of how do we stop talking long enough to listen. Because just like with everything in the writing world and how the noise sort of blocks out hearing the story, there’s a lot of noise in our lives and interactions with one another that blocks out actual movement towards progress.

Yeah. I think it’s just about taking a step and doing one right thing. And then another baby step, doing the subsequent right thing, and just asking what the next right thing to do is. We tend to look ahead towards the end, which is good, you know: keep your eyes ahead on the light at the end of that tunnel. But we cannot get to the end of that tunnel if we don’t take the steps now. We have to move through that tunnel. If not, we will just stay here, looking off at that place — a utopia where everyone is happy, equal — and we will never get even close. So even if the near future looks bleak, it gives me hope that we are taking those single steps, making some progress. If we were not, then I would really be afraid. In Nigeria now, the masses can rise up and say “No, we don’t want this,” and the government will listen. Even now it’s still difficult, but at least they would address us. Before, the government would behave as if we were not talking, as if their ears are plugged. So for the government to listen now, for me, is a step. And if we make enough of these baby steps — from carrying our heads, to rolling on the bed, to crawling, to walking and falling — we will get to that point where, eventually, we can walk.

All Shades of Iberibe

All Shades of Iberibe

Kasimma

Sandorf Passage

November 2021

Joseph Demes is the editor in chief of Long Day Press. His writing has been published in print with METER, Oyez Review, and Sobotka Literary Magazine, as well as online with Hobart After Dark, Essay Daily, and [PANK]. He has received support from the Sundress Academy for the Arts, the Tin House Writers Workshop, and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he completed his MFA. He lives in New York.

This post may contain affiliate links.