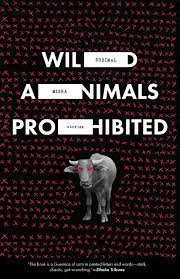

[Open Letter; 2021]

Tr. from the Bengali by V. Ramaswamy

The Bengali writer Subimal Misra writes anti-stories, subverting the norms of short form fiction and, instead, using language to build mosaic style capsules to challenge literary form. He is fiercely anti-establishment, only publishing in Bengali language “little magazines”, a publishing movement born in the 1950’s promoting modernist, anti-establishment work. And he never sought payment or commercial publication for his stories. He says, “I do not want my writing to be converted into a commodity, or be capable of being digested in the intestines of middle-class babudom. I want to make writing into a weapon against repressive civilization.” From this determinedly outsider viewpoint, Misra has dissected the hypocrisy of bourgeois Bengali society, and the continuing famine and political corruption, for over fifty years.

Wild Animals Prohibited, published by Open Letter in 2021, and previously by Harper Perennial in 2018 in a special edition to commemorate their finest work in translation, collects Misra’s earlier work from the 70’s and 80’s and reflects many of the political and cultural upheavals within Bengali society during this period, particularly the Naxalite Uprising of 1967 and the controlling powers of the Indian Communist party. In the opening title story, ‘Wild Animals Prohibited’, a married couple’s apartment is the setting for an illicit bourgeoisie sex party where the maidservant is locked in a cupboard and, in the street below, people live on stretched out newspaper. A beggar girl with a baby in her arms regularly knocks on the door — “She stared at us with wide eyes as we fondled each other. Sometimes one of us got up in exasperation and twisted her arm.” They also spit at her and splash her with boiling water, for (in their view) enjoyment. They do not talk about the people living on the newspaper below because “ they knew very little about the people, and consequently their discussion lacked substance.” Misra shows how the visible, contiguous poverty of those beneath does not lead to understanding or empathy on behalf of the party goers, instead they display bafflement and confusion. It is not just the cruel superiority of the affluent class that Misra critiques, but also ignorance of the wider society outside.

Whilst the middle-class debauchees may be clueless to society’s imbalance, Misra’s stories refuse to allow readers the same blindness as he exposes the callous extremities of life on the streets and riverbanks of Bengal. His characters reflect an underbelly of hunger, oppression and authority using avant garde techniques, adding factual evidence, statistics and powerful, surreal imagery. The story, ‘Wild Animals Prohibited’, is one of the more formally familiar stories in the collection written in the traditional form as a realist tale rather than with Misra’s usual disruptive approach. Misra refers to his stories as ‘chobi’s’ or films, and it is the language of cinema rather than literature that typically characterizes the imagery and construction of his ‘chobi’s’. In the same way Godard employed jump cuts and Eisenstein applied montage in their films, Misra forgoes an easy narrative flow, preferring to intersperse and cut up stories with often seemingly unrelated text. In ‘Radioactive Waste’, Sushma and Ajoy consummate their relationship to the “sound of country bombs exploding outside — the old problem had cropped up again in the neighbourhood.” As they discuss their futures whilst more bombs fall, sections of reportage and folk tales along with poetry and scientific writings on the formation of human cells are spliced into the story. This creates a kaleidoscopic effect, reassembling imagery and ideas, allowing the reader different ways of assessing Sushma and Ajoy’s story alongside textural information such as biology and true events. When Sushma becomes pregnant, the cross section of data on radioactivity and the various newspaper accounts of the war in Vietnam, take on a symbolic meaning. This is not just the story of a relationship but a reflection of the moral and mechanical reality facing new life. By removing the reader from Susham and Ajoy’s story, Misra points to the wider habits and destruction in society and the inevitability that their unborn child will be born into a nuclear, ravaged age.

The human body as a symbol of sexual and political control is a common theme throughout the collection. ‘Spot Eczematous’ begins: “Once there was a bad man and his soul was small and soft but fleshy. He put it in a paper bag and shoved it under a pillow.” In the story, the bad man’s soul finds its way inside a boy who finds companionship with a girl who eats the lice from her hair, regarding it as food for the proletariat. Having ingested the soul in a beef roll, he begins to feel worse for wear — he vomits and hallucinates. The text is intertwined with larger fonted, statistical information about India’s hunger crisis and how women, in certain regions, are used as economic dependencies, forced to live in harems until a husband’s debt is repaid. Perhaps, as Misra seems to be suggesting, parts of India have ingested the soul of a bad man too; the imagery throughout much of his work represents a frailty and sickness on display and a hallucinatory quality, as if entire regions had indeed imbibed a bad soul and, like the boys ailing body, lost the ability to see sense and function reasonably.

The transgressions of the human body allow for surreal metaphors to be understood in a strongly visceral sense. In ‘Wild Animals Prohibited’, body parts are continually being found or removed; while ‘In Babbi’ portrays a man who lost an arm as a child and finds a new arm in a garbage vat and stitches it to himself. In ‘36 Feet Towards Revolution’, Subhendu is shot in the street and taken to hospital. After the operation he is discharged with his heart in a paper box. The girl, who is also without an internal heart, keeps her heart wrapped in cellophane inside her handbag. In this story, the world Misra describes has lost its compassion, and so there is no longer any requirement to have a heart; for only those without a heart could allow for hunger, exploitation, war and oppression to persist. Misra’s characters do not always have control over their bodies, they are at the mercy of repression. Carrying his heart, Subhendu sees written on the wall, “power flows out of the barrel of a gun.” It is a power that has removed Subhendu’s heart and built a society of heartless citizens.

In the preface to this collection, Misra says, “Everyone wants to be a big writer. I don’t want to be a big writer at all. I want to be a completely different kind of writer.” His alternative, collage style approach to writing, fearlessly baulking against popular representations of the short story form, offers a new generation of English speaking readers (through reissued translations) the chance to discover an important voice in politicised experimental fiction. Wild Animals Prohibited is a remarkable collection of strange, unwelcoming stories, with a serious desire to disrupt complacent attitudes of the literary world. Misra does not seek popularity or a readership, his work is designed to relay the discomfort and inequality within the divided echelons of Bengali society, and reflect the unseen brutality of life for those living and coping alongside the prosperity of their neighbours under the regime and watchful eye of a bourgeoise population that shows little interest in affecting change.

Simon Lowe is a British writer and journalist. His stories have appeared in Breakwater Review, AMP, Storgy, Firewords, Ponder review, and elsewhere. He has written articles about books and society for the Guardian and BBC worldwide. His new novel, The World is at War, Again, was published in 2021 (Elsewhen Press).

This post may contain affiliate links.