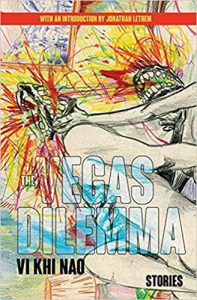

[11:11 Press; 2021]

Let’s begin at the beginning. Vi Khi Nao’s The Vegas Dilemma is a new story collection out from 11:11 Press, Nao’s seventh book since 2014 and her second collection of stories following A Brief Alphabet of Torture, winner of FC2’s 2016 Sukenick prize. Having had her poetry and fiction published by similarly renowned presses including Nightboat and Coffee House, her work featured by The Paris Review, and receiving prestigious awards while an MFA candidate at Brown, Nao has enviable and well-earned bona fides. She is a unique, independent, and compelling voice in contemporary letters.

Oddly, the opening section of The Vegas Dilemma isn’t authored by Nao. Rather, we are greeted with a foreword by fiction writer Jonathan Lethem. Forewords are fairly common in reissued books, translations, and anthologies, but I don’t recall ever seeing a foreword to a newly minted single-authored book. (I wonder if it’s a gambit to bring more attention to The Vegas Dilemma in an attempt to boost sales — if so, it’s a little saddening.) Stranger is the foreword itself. These are usually gigantic blurbs under the veil of criticism or introductions that celebrate the work to come, highlighting specific themes or craft aspects, warming the reader up for a pleasurable experience. Lethem focuses on meeting Nao at a Pitzer College reading in February 2020, and about how now, looking back at that event, both he and Nao feel her reading was the “last thing” before the pandemic. That’s mostly it, though he does end by quoting Nao in another interview speaking about her writing process. It’s a strange way to begin a book — with someone else whimsically musing while the book we’re about to read verges on being an afterthought. (Stranger still: my wife and I were at that Pitzer reading. We live near Lethem and would recognize him quite easily. We don’t remember seeing him there.)

All that to say: Let’s not make this foreword thing a trend.

I will happily say more about the actual content of The Vegas Dilemma. To begin very factually: The Vegas Dilemma is a tightly sprawling collection of 27 stories, 14 of which check in at five pages or less, the others running an only somewhat longer 6-11 pages. So these are stories more of brief moments and passing interactions than they are focused on events that play out over weeks, months, or years. The physical book is a trade paperback with cover art by intertextual artist Tiffany Lin, who provides a great chaotic abstract splattering: A couple having sex? Killing each other? Both? The book’s back features a yellow box filled with faint blue microscopic text: Blurbs? Summary? The color contrast and font size make it almost impossible to say, which is maybe fine, at least if it’s an intentionally thwarted expectation up Nao’s aesthetic alley.

The stories in The Vegas Dilemma have recurring themes of solitariness, night, passing encounters with strangers, sex, food, hunger, and power — to name a few. The main characters are often very body aware, usually alone in life, and spend much of their time wandering through spaces not their own. Here, transit is common, unsettlement is common — yet both are rendered passively. Characters frequently have to move along, say, because the Starbucks in the grocery is closing once more — but it’s not much of a bother for the characters, and it doesn’t much matter where they go next. “She is wandering the streets again,” a line in “Not Capable of Giving Her Leprosy,” could serve as tagline for half the collection. A nice observation from Lethem’s foreword — it’s not so bad — notes the prominence of melancholy in The Vegas Dilemma. If Lethem knows the etymology of the word, as is likely, his observation is so much the better: these certainly are stories with an excess of black bile.

Twelve stories in the collection, including the first seven, are unsurprisingly set in Las Vegas (per the book’s bio, Nao was a fellow at Black Mountain Institute in the fall of 2019). For most of the Las Vegas stories, we follow what seems to be the same character, suggestively a stand-in for Nao herself: a writer wandering the city. A passive outsider critically observing the empty entropy of existence? This is a premise I’m all for, but, sadly, this doesn’t really take hold, as the point of view character isn’t generally observant about anything other than herself. We go for example again and again to a Smith’s grocery store, but the Smith’s never emerges as a three-dimensional setting populated by three-dimensional characters: it doesn’t accumulate because, for the point of view character, it barely matters. It’s just another place she goes. In conventional fiction, events progress and lead the reader forward; convention is clearly not where Nao’s interest lies. We aren’t given particularly complex characterization or impactful relationships between people, either, and in many of these stories, it feels like Nao isn’t pushing so much against the form as she is indifferent to its conventions; the stories aren’t radical so much as they are small.

Smallness in fiction can be liberatingly light, and The Vegas Dilemma carries a great deal of lightness. Rather than being sequential and progressive, time throughout the collection is both static and expansive. One might say this is precisely the Las Vegas experience, but that’s merely the stereotypical canned casino experience, and the Las Vegas-ness of the stories is one of the collection’s disappointments — a familiar this-city-is-so-vacuous take:

She stood there gazing out at the nocturnal, desolate traffic of the sinful but sinless city. Everything was sprawled out, including the air and its cars. People had already rushed home to eat their saturated-fat dinners with takeout burgers, fries, and decadent donuts . . .

I don’t know Las Vegas particularly well, but I do know I’ve seen this one in other works. I wonder if the city is a trap for writers — if, given how strange and singular it is in the American landscape, how much it seems to symbolize the gaudy worst of capitalism, a writer can’t help herself from passing familiar judgment. John D’Agata’s About a Mountain and John O’Brien’s Leaving Las Vegas come to mind — these books, too, focus on the bad platonic Las Vegas we all know and loathe. But other writers, such as Vu Tran, Lee Barnes, and even Hunter S. Thompson, write about a Las Vegas all their own. It’d be nice if Nao’s Las Vegas were more distinct.

Happily, many stories in the collection are set free from the city’s confines. These latter stories have a bit more strangeness of form and language, are less predictable, and travel different roads. Unlike the Las Vegas stories, which have the through-line of character and setting, these other stories don’t carry any narrative expectation of movement, of growth, of progress. The prose itself becomes less constrained, and what one probably hopes to find in a collection of stories by Vi Khi Nao emerges with a great deal of force. In “What I Starved Before Turning You Into Blue,” we see a wonderful example of Nao in motion:

I haven’t pretended to be panthers. I haven’t pretended to be pantyhose. I haven’t pretended to be anything as I compress every inch of spring into earth.

The panthers and pantyhose don’t serve the story’s narrative — which is great. They’re words that emerge from the words before them — and that, if you’re game, is more than enough. Many writers write gorgeously. But Nao, free from narrative, repeatedly summons the equivalent of spit-takes:

True power requires one to be dick-deaf. (“Not Capable of Giving Her Leprosy”)

She wanted to punch the face of the wind. (“Mother Nature Is Belligerent”)

When the stranger opened his mouth wide, she saw yesterday swollen like a crushed pregnant bird. (“The Uzi Could Be a Landscape of Love”)

And it’s not just the occasional flash of sentences that gives the shine to The Vegas Dilemma. Every time I’m tempted to describe these stories as grim, I remember how feisty they are; every time I want to say they’re melancholy, I remember how funny they are. In “Lonely Not Like a Cloud,” the point of view character masturbates to YouTube videos of Kristen Stewart in the hopes of opening an actual portal between them. Why not? At its best, the lively lightness suffuses entire pieces; they become not weighed down but joyful in their ebullience. Several of the stories are stunning, for varied reasons — for the mastery of tone, the leaning into the lyrical, the diving into motion that says to the reader, swim with me or drown. “Love Story With Bifurcation and Violation” closes the collection as a twelve-page single paragraph in which a first-person narrator addresses maybe a lover or a something or a self? This all occurs in a relentless stream of shifting brief sentences that veer between the concrete — “Your hand is touching me”— and the metaphorical: “If I walk closer, I can open the wallet into your mouth. There is money there . . .”

To say that The Vegas Dilemma is an uneven collection of stories is to say that it’s a collection of stories. While I’ve dwelled a bit long on the Las Vegas stories, they’re actually in the minority — it’s the fifteen other stories that make this collection remarkable. So many reach impressively high in terms of form, tone, strangeness, and, yes, language — “Callously Touched by a Maniacal Man,” “Sky Is No Longer on Vacation with a Hole,” “Vignettes: Explorations of Certainty and Uncertainty,” “What I Starved Before Turning You Into Blue,” “Calm, Calm, Calm, Rupture”; I could go on and on. Taken together, this is not only a good book, it’s a book of possibility, one that lays out the risks, dangers, and rewards of unconventionality. It is strange, imperfect, and beautiful.

Sean Bernard (anotherseanbernard.com) is the prose editor of Veliz Books and the editor of Prism Review, and he serves on AWP’s board of directors. His stories have appeared in numerous journals, and he’s the author of the collection Desert sonorous and the novel Studies in the Hereafter. He directs the creative writing program at the University of La Verne.

This post may contain affiliate links.