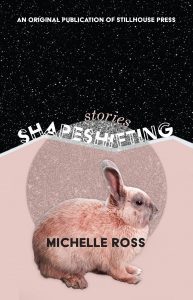

[Stillhouse Press; 2021]

Set in the present-day United States, Shapeshifting is a collection of fourteen short stories which offer an unsparing meditation on pregnancy and motherhood. Michelle Ross engages with multiple points of view, including children, grandparents, and rape victims, while depicting protective mothers, insouciant mothers, grieving mothers, and mothers of handicapped children. This is only a partial list. As the title aptly suggests, there is no “one size fits all” narrative to accommodate the experience of motherhood, and Ross is wary of the pat or consensual.

The book opens with “After Pangaea,” a witty and insightful tale that addresses the follies of competitive parenting, where mothers and fathers go to great lengths to obtain places for their children in a select preschool. It emerges that the worst kind of competitive parenting occurs within couples. The narrator’s husband, a man so hapless, domestically speaking, that he can’t slice an apple, enjoys a freakish success as a blogger dispensing his opinions about parenting. Like Chance the gardener in Jerzy Kosinski’s Being There, his banal observations are overinterpreted and given great weight by admiring fans, who credit him with a precious masculine sensitivity. Meanwhile, his wife does all the heavy lifting.

Many of these stories, though, take the reader into darker territory. In “Shapeshifting,” which lends its title to the collection, a pregnant woman who is herself a child of rape receives taunting postcards from her depressed and agoraphobic mother. Here and elsewhere, as in “Galactagogues,” Ross takes the seemingly straightforward concept of personal agency, and dramatizes how complicated, and vexed, the concept can be. Along with external pressures and coercion of politics or family, there are internal and biological imperatives, over which the mother has no control, and which can challenge an individual’s sense of self. “I’d always pictured myself behind the wheels,” remarks the narrator of “Shapeshifting,” [but] this is the opposite. I’m the wheels, not the driver.” Ross has a keen eye for images. While in labor, the narrator observes, “I am like a tiny crab on the sand watching that skyscraper of water darken the sky.”

That skyscraper of water looms large in “Three Week Check-Up,” “The Pregnancy Game,” and “The Difference Between Me and Everyone Else.” Characters cannot control how or when the wave will come crashing down. Sometimes they don’t know it’s there until it’s too late. Deena, a sleep-deprived young mother in “Three Week Check-Up,” feels “like discarded wrapping paper at a birthday party.” She can never go back to being her previous self. The narrator of “The Difference Between Me and Everyone Else” ruefully witnesses how some people can behave irresponsibly and get away with it, while others pay a terrible price: the blithe and tragic exist side by side.

Ross’s aversion to neat, easy answers is complemented by a gift for dramatizing evidence to the contrary. This is the source of her subtlety. Many of the stories have open, Chekhovian endings. The comfort of resolution is not nearly as interesting as the surprise and mystery arising from observable ambiguity. A few stories, like “The Natural Order of Things” and “Winkelsucher,” are more essayistic and idea-driven, but these share a similar sensibility. The latter story addresses the moral implications of photographing children, who don’t enjoy the privacy that adults might expect or who are more easily manipulated (“Between shots [ . . . ] parents wave cookies like dog biscuits.”) The desire to document competes with observer bias as the subjects of the photographs are inescapably “experiments — messy, uncontrolled, long-term experiments.”

Lastly, Shapeshifting occasionally ventures into more speculative or dystopian settings. “Keeper Four” depicts a society where birth control is illegal, many are dying, and a protagonist works at a research facility studying interspecies relationships. A grizzly bear has a mother relationship with a small child. Could drug research perhaps develop (and prescribe?) medications to produce (or impose?) the maternal instinct? Here we return to the problem of personal agency alluded to earlier. In “A Mouth is a House for Teeth,” a mother and daughter stay locked up at home, fearful of stepping out into the world, respecting protocols insisted upon by an often-absent, controlling husband. They survive on supplies dropped by drones. The story is permeated by an uneasy ambiguity: is the outside world truly such a threat or does this dystopia exist in a psychological space within? Is the narrator the victim of a political system or of an endocrine system?

You can never be certain when your desires and behaviors are ruled by hormones and when they are not. Perhaps when she wishes the husband were dead, that is hormones. Perhaps the moments she feels tender toward him are the products of hormones. Perhaps when the mother stands at the window and watches the neighbor woman walk out of her house in T-shirt and shorts and sneakers and take off running down the street, no apparent worries about being a woman alone on a street, and the mother longs to abandon the girl and run out after the woman, that is hormones. Perhaps remaining at the window instead of joining the woman is hormones.

Perhaps her autonomous self is dear illusion, nothing more, and she is the prisoner of chemical forces. Of course, predictive accounts about women’s hormones have a long and unfortunate history, but Ross is doing something different here. It’s less an old-fashioned determinism than a dramatization of distress. Empowerment is a seductive ideal but this character cannot own the desire for it, and thus she is able to wonder: what if it’s all a chimera?

Consistently inventive and sometimes provocative, Shapeshifting is an accomplished collection of short stories and a convincing follow-up to Ross’s first book, There’s So Much They Haven’t Told You, which won the Moon City Press Short Fiction Award. Ross’s writing probes and tests assumptions that we often take for granted, and raises questions that will leave the reader musing, long after a story is finished.

Charles Holdefer is an American writer currently based in Brussels. His work has appeared in the New England Review, North American Review, Chicago Quarterly Review and in the Pushcart Prize anthology. He is the author of nine books, most recently AGITPROP FOR BEDTIME. Visit him at www.charlesholdefer.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.