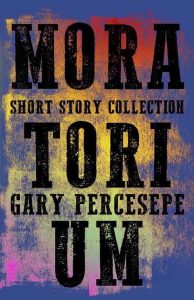

[Atmosphere Press; 2021]

I love it when a writer’s acknowledgements page is an essay as opposed to a list of the mentors, friends, and connections along the way. In the acknowledgements of Gary Percesepe’s new collection of short stories Moratorium, he tells the story of how he came to work as an editor at The Antioch Review under the tutelage of longtime editor Nolan Miller. The scene is cinematic: at the time, Miller was legally blind and lived with his brother, who was deaf, in identical bachelor’s apartments in a shared house in Yellow Springs. Percesepe would come over and read stories aloud from the slush pile while Miller interjected and they’d linger on the merits and shortcomings of every story. In this way, Percesepe describes the inheritance of an aesthetic preference. What did Nolan Miller want in a story? “He wanted something made up. He wanted to be surprised, [the story] infused with a sense of wonder. He wanted dramatic pace, for we as readers to be asking ‘And then? And then?’ He admired stories that were told confidently, with authorial precision and lack of pretense.” Percesepe worked in this way as assistant fiction editor at Antioch Review and he would later continue this work at Mississippi Review Online, where he’s still a guest editor / contributing editor under its current iteration, New World Writing.

Frederick Barthelme took over Mississippi Review and started The Center for Writers at the University of Southern Mississippi in 1977. He’d been the director of an NYC art gallery, he was the alumn of a psychedelic band, and he was Donald Barthelme’s younger brother. There was no way Mississippi Review under Frederick Barthelme was going to be like all the other literary journals. Frederick Barthelme described the magazine at this time as:

…a “new” gen magazine. We made an effort to publish the work that was just happening then, folding in a few more well-known writers we thought of as forebears of some sort as well as new writers who were post Donald Barthelme, Jack Barth, Jack Hawkes. And we also were looking for any work that looked and smelled new or newish. We were sort of desperately trying to find anything at all that wasn’t the same old shite that then appeared in lit mags.

For nearly two decades, Mississippi Review did as much as a paper journal could do. In the mid-1990s, Mississippi Review Online was one of the first already established literary magazines to engender an online counterpart. MRO was a distinct entity from Mississippi Review and a place where one could find shorter work, stories by Rita Dove, John Barth, Thom Jones, and Gordon Lish alongside stories by Robert Olen Butler, Ben Marcus, Christine Schutt, Ron Carlson, and Tao Lin, all of it free. When editors and writers were still figuring out what to make of this new medium, Frederick Barthelme was desperately seeking the new in a new way. Mississippi Review Online is an important snapshot of the time, and the archives are still online.

Barthelme and Percesepe had met and struck up a friendship around this time. Barthelme had published Percesepe in Mississippi Review and he brought Percesepe on board as an assistant editor / contributing editor of MRO, so Percesepe was there in the middle of all of that and surrounded by a lot of talent. The advice often given to writers is to read, read, read. But for those in a position to do so, some better advice might be to edit, edit, edit.In his acknowledgements, Percesepe said, “If Nolan taught me to read and edit, Barthelme taught me to write.”

Percesepe’s stories were published in traditional venues like Story Quarterly, or the now defunct Houston Literary Review, but one can feel the tightening and shortening of his stories as fiction went online and Percesepe published in venues like FRiGG, Wigleaf,and Necessary Fiction, with the first piece in the collection the longest, and the last piece five short paragraphs. The difference is stark, and while both are considered fiction, what they aspire to, and what they accomplish are quite different. The pieces in this collection demonstrate that transformation, his trajectory as an artist parallel to his trajectory as an editor, from being the assistant editor at Antioch Review, where the New Yorker story could thrive, to being an assistant editor at Mississippi Review Online, where brevity and the possibility of fiction renewing itself was sent out for free to be read on screens.

The title story, set in Vietnam-era Yonkers, is about the loss of the main character’s two siblings, one to an accident and one to radical 1960s anti-war politics, and the coming of age of Joe, smitten with the girls growing up around him.

The title story, set in Vietnam-era Yonkers, is about the coming-of-age of Joe, who loses his two siblings (one to an accident and one to radical 1960s anti-war politics). His parents are forever changed while Joe tries to cling to normalcy and distract himself in young love. When Joe asks an uncle where his brother is buried, he’s told:

“Geez, Joe.” He ran his manicured fingernails through his curly hair, gestured vaguely over his shoulder and said, “Over that hill, on top, that way. It came so sudden, none of the family had any plots out here yet. We just looked in the yellow pages and found this place.” We stood silent for a while, standing up to the blasts of frigid air coming out of the north, looking up at the hill. He tugged at the collar of his topcoat.

Joe’s older sister disappears after she’s involved with a political bombing and Joe spends the following years unable to reconnect, “I began to have the sense that I have had ever since, that I didn’t want to belong to anything, that I was not a joiner.” In this rapidly changing world now lost to us, where children are sacrificed to ideologies or accidents, where the characters are hurt and horny, there aren’t any answers to the big questions, and we’re left to roam a beautiful icy world. Sadness and joy are inextricable here. Conflict remains unresolved. “Moratorium” represents the kind of literary story that could be found in Nolan Miller’s Antioch Review, less interested in plot than in character, atmosphere, scene, and sentence. According to Percesepe’s description of the “no longer sighted” Miller, “ . . . his ear was keenly attuned to the musicality of stories, the right words in the right order.”

Throughout the collection there are nods to great art and philosophy. There are characters aware of their namesakes from J.D. Salinger stories. There are allusions to Franz Kafka and Max Brod, to Proust, to Rilke. Percesepe is a philosophy professor at Fordham and a church pastor, after all. But the pop culture references far outnumber the literary ones, and his humanism outweighs his intellectualism. When asked about the connection between Percesepe’s writing and his work as an editor, Barthelme said:

Gary’s work is always interesting and evocative. He takes interesting topics and interesting angles on things. What you must realize is that he is exceedingly bright and thoughtful, has read widely, and has a very sharp eye for complicated subjects treated in fiction, philosophy, poetry. At the same time he is something of an activist in the conventional sense of that, political and social.

There’s never a question of the rightness or wrongness of Joe’s older sister’s actions in response to the Vietnam War, but the disappearance of the sister from Joe’s life is deeply felt.

Percesepe explores the space between sex and love. Throughout the collection are pieces set at the ends of relationships, or at the beginnings of new ones. After his divorce, a middle-aged man in the story “Girl, Interrupted” wonders, “If he was no longer married, who was he?” only to find redemption in art. He’s saddened that he never knew his ex-wife as a girl, and he wallows in the feeling as he can’t walk away from Vermeer’s “Girl, Interrupted at her Music.” In short pieces like this one, Percesepe conjures a depth of feeling with only a kernel of story. As it’s bluntly stated in “Wonder Seat,” “It takes only a few decisions to make an affair.”

This is a collection of work that spans twenty-five years, from Percesepe’s time as assistant editor at Mississippi Review Online through to the present to his time at New World Writing. Just as American fiction has undergone a change because of the influence and confluence of writers and writing on the internet, there’s a similar evolution in Percesepe’s stories, from the complex early stories that would be at home in The New Yorker, to the later sprinting flash fiction. We read on screens now, and we tweet, impatient with excess. The New Yorker is, of course, still around, and the traditional short story persists, but for those who don’t know it yet, this is the age of flash fiction, and Percesepe is a well-adapted boomer. There’s a great variety of experience here, and it feels like he’s still in conversation with Nolan Miller. One can imagine Percesepe reading from his life’s work to his much older deceased friend, and Miller taking in each sentence, an expression of concentration on his face as he reacts with surprise and delight. Percesepe is clearly haunted by the past, and he’s taken great pains to give it to us. As a girlfriend tells the main character of the story “Giocometti,” “I’ve lived with death my whole life. And I know the people we love we carry with us, always. They are part of us.” For anyone who spends time with Percesepe’s Moratorium, they’ll be a part of us too.

John Minichillo is the author of five small-press novels, including The Message in the Sky (forthcoming, Spaceboy Books) and The First Woman on Mars. He lives and teaches in Tennessee.

This post may contain affiliate links.