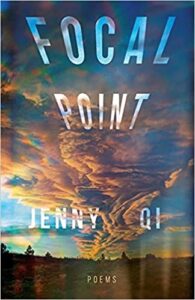

[Steel Toe Books; 2021]

A culture as ostensibly committed to individual happiness and wellbeing as ours has a difficult time making sense of loss. It is worth considering whether we are even capable of the kind of grieving that lets blood from the chiseled stone of “wellness,” the kind of grieving that resolves into a truer orientation to self and society, regardless of whether it is a happy one. Scientists, therapists, life-coaches, even our profit-seeking bosses implore us to bereave our losses, feel our feelings, live our truths. Grieve, but go back to work on Monday; mourn, but do not lose yourselves in your mourning. It is as if everyone who has a credential to give advice is now of the opinion that grief should not be transformational, that it is an unfortunate, if unavoidable, digression from the business of living well. On such a view, the person who loses themselves completely in grieving, who lets their entire life be consumed by it, appears as if they simply do not know how to do it healthily. They appear unaware that the point of grieving is to emerge out of it harder, better, faster, stronger than when one began. Choose the method that works for you: read the Nature article about the brain chemistry of grief; keep a diary as you journey through its five distinct stages; study the seven habits of highly effective mourners; and so on. But what if, in the course of their grief, the person becomes so immersed that they cannot extricate themselves from it? What of that soul who does not know how to grieve properly, who perhaps refuses to learn, who experiments with different ways of grieving, not in order to come out of it improved, but to do their utmost by the departed?

Jenny Qi’s debut collection, Focal Point is an account of the poet’s decade-long journey through grief. The bereaved is, first and foremost, the poet’s late mother, whose death from cancer in 2011 is the book’s primary focus. Qi studies this loss from as many perspectives and points in time as there are poems in the collection. Although we encounter the first-person voice almost exclusively, these poems are multivocal, dialoguing constantly with the poet’s parents, a younger brother who dies in the womb, doctors and patients at various hospitals, old friends, new lovers. The book’s four divisions mark watershed moments in the poet’s grieving — the first days after her mother’s death, a year after, five years after, ten years after — but do not necessarily equate to stages in a linear process. Ten years elapse across these poems, and yet, just when we think we know where we are in time, the poet inserts a flashback to a childhood or adolescent episode that upsets the illusion that time moves inexorably forward. For every small triumph over tragedy, Qi reports an equally weighty setback that reverses her hard-won progress. Focal Point, like the Greek epics it frequently references, is thus an inner odyssey through illness and loss that imparts the difficult lesson that to live is to grieve.

The collection’s opening poem, “Point At Which Parallel Waves Converge & From Which Diverge,” is a memory-sequence that begins in the hospital where the poet’s mother is dying and ends in a sterile laboratory where the poet is injecting cancer cells into hundreds of mice. This early attempt to grieve her mother through medical research (Qi earned a PhD in Cancer Biology from UC-San Francisco while composing many of these poems) runs into difficulties from the start. Science explains the rapid advance of cancer in her mother’s lungs, but only as far as proving “why I couldn’t save what I couldn’t save.” Caressing each little mouse as she delivers it a lethal injection, the poet sees “my mother in [their] graying eyes” and considers the futility of “all this erratically focused empathy.” In just a few spare verses, Qi sets herself a task that will take the length of the book to fulfill: to bring order to the disorderly experience of losing her mother, to bring “all this erratically focused empathy” toward a focal point of meaning. The form of the opening poem itself – twelve unevenly metered couplets – indicates that poetry has at least some ordering power, even if its first attempts do not fully master grief’s unruliness. This striving for greater order persists through other poems such as “Palmistry,” “Normal,” “Winter,” and “Magnificent Things,” all of which start out in open verse before resolving into couplets or quatrains with more musical meters.

In the book’s first division, Qi follows a familiar literary light. Several poems allude directly to Joan Didion’s Year of Magical Thinking, the now-classic account of how Didion grieves her husband’s death from a sudden heart event. The so-called “magical” element in Didion’s thinking is her notion that an irreversible loss can be undone by the griever’s will. For example, Didion believes for a time that studying the causes of her husband’s death will somehow give her contra-causal power over them. Half-aware of but unable to stop what she is doing, Didion turns scientific objectivity into a servant of subjective derangement. Like Didion with her husband, Qi studies her mother’s illness, hoping, perhaps, that understanding it better will somehow alter its tragic course. However, as Qi becomes more aware of science’s conspiracy with magical thinking, she begins to demote its authority in her worldview. Recounting her mother’s final hours in “The Last Visitation,” the poet rejects all interventions not aimed at easing her mother’s passing: “Blood diagnostics? No./Defibrillation? No./My vision blurred over the words.” By forfeiting her hope in medical science as a potential savior, she enters into the radical mode of grieving that comes to define her next decade. What makes her grieving radical is that it refuses to hold on to any familiar epistemic bearings. It is an experience of pure loss, of being totally unmoored from any metaphysical comforts. Losing her mother means nothing less than losing the ground of all her beliefs. (Just before rebuffing the doctors’ offers of further medical interventions, the poet “refuse[s] the chaplain,” making it clear that she will not simply turn to another form of consolation just because science’s credibility has collapsed.)

Later in the first division, however, the daily grind of grieving opens the poet’s mind to alternative methods of working through loss. In “Letters to My Mother,” the poet who earlier refused the chaplain now “burn[s] messages on colored paper” and “[blows] sandalwood ashes to the wind.” “I never believed in anything,” she writes, “Now I believe in everything,/all the rituals of all the faiths.” Ashes become the symbol of Qi’s ecumenical outlook, the holy substance that links all the rituals of all the faiths together. She burns sandalwood, paper cranes, letters, poems. She imagines herself borne back to her mother “in ashes of paper wings.” A later poem, “Postcards from the Living,” reveals that Qi’s turn toward superstition has been conscious and deliberate: “I light ashes on the stovetop, trail cinders/through an empty house. I’ve decided to believe/in the power of ashes.” Still, this somewhat effortful performance of the sacraments suggests that Qi’s embrace of an all-encompassing faith is far from total. After forfeiting trust in one system of meaning, can a person just choose another, as if belief were merely a matter of will? In “Reading Horoscopes During a Long Convalescence,” Qi hints that her sudden about-face toward spiritualism may not be wholehearted: “Last night I dreamt I turned into a ram,/like my astrological sign, not that I believe in such things . . . ” It would appear that, like science, superstition has its limits, too. Consider what happens to the symbolic status of ashes across these poems. At first a medium of communion with her departed mother, ashes lose their spiritual aura completely in “Casino,” now dusting the laps of the chain-smoking gamblers from whom her mother, a casino card-dealer, “bought [cancer] second-hand.” Even the holiest of substances is profaned by mixing with brute reality. All the rituals of all the faiths fail to add up to deliverance.

Qi’s struggle to find her intellectual bearings leads her to embrace poetry as the most reliable – albeit far from failsafe – method of processing grief. Her poetry combines elements of science and magic in attempt to supersede them. “Telomeres and a 2AM (Love) Poem” is a good example of this. Reading from a medical textbook as her lover sleeps, the poet has the “sudden brilliant thought” that telomeres, the end-parts of chromosomes, have something to teach us about love’s natural cycle. Her thought’s suddenness distinguishes it from science’s painstaking empiricism, at the same time that its directedness toward external matter distinguishes it from mere magical thinking. A melding of science and superstition, poetry brings a new kind of object into focus: beauty. “Magnificent Things” is illustrative. Here, Qi has a surprise encounter with a peacock that flares its tail just as she snaps a photograph of a rose in its enclosure. For her, the peacock’s beauty is a medium between spiritual and material realms. Its tail is “a sign/of good things to come,” a little fragment of magic whose magnificence, somehow, is “flimsy,” “waving like a skeleton hand,” a reminder of her mother’s mortality. Qi shares a memory of a time she and her mother saw a peacock together, her mother calling out to it, “Piao liang, pretty bird/won’t you open your tail? . . . /It never happened/in her lifetime.”

“First Spring, 2020” is another study of how poetry processes grief through beauty. Here, surrounded by chirping birds and blooming flowers under a San Francisco sunset, Qi ponders “this light,/the dissonance of grief in the spring . . . /A knot blooms in my stomach,/a bitterness bubbling in my throat.” These lines are meant to be juxtaposed with their companion verses in “First Spring, 2011,” composed the spring the poet’s mother passed. In the 2011 poem, the birds are not chirping; they are “fucking in the sky.” Pink flowers, meanwhile, are “too eager to last the spring . . . /as if beauty still matters.” Where the 2011 poem views beauty as an affront to grief, its 2020 counterpart views beauty as grief’s proper object, even if it does not ultimately sweeten its bitterness. It would seem, then, that there is no final outcome, no terminal grief process, in Focal Point. Beauty flirts with the eye as dread churns the stomach. To paraphrase Qi, rediscovering that there is meaning in life is no substitute for what has been lost.

Qi makes this same point transcendently in “Call & Response,” a hybrid piece comprised of a translation of a classical Chinese poem by Su Shi and an original response by Qi. Su Shi’s poem portrays a graying widower who continues to grieve his departed wife ten years after her death. “I don’t think of her often, yet neither can I forget,” he writes. In his dreams, “she dresses by her window, stains her lips and cheeks red,” and the two watch “a thousand tears line the other’s face.” Grief’s directedness toward beauty is crucial here, as is the idea that beauty does not assuage grief so much as focus it. Qi’s response, which is written from the deceased’s perspective, imitates the translation’s form and content, creating another focal point on which the two poems can converge and diverge: “On the dark wooden table, the red stain for my lips has dried . . . /We weep together . . . ” At no other place in the collection does Qi so thoroughly demonstrate poetry’s capacity to bring order to grief without overcoming it fully. Her translation carefully adapts the monosyllabic meter of the Chinese original (7-6-9-7-6) into a multisyllabic, musical English, while her response answers Su Shi’s verses line-by-line, recycling his poetic images into something remarkably new. Rather, she constructs a series of focal points “at which parallel waves converge and from which diverge,” images of a life lived in the ever-widening shadow of loss.

If we accept Qi’s thesis that to live is to grieve, then we unlock another of her major themes, namely, that grief is both past- and future-oriented. This is most apparent in the collection’s many love poems, all of which, in one way or another, connect the blooming of erotic love to the body’s inexorable decay. “Telomeres” compares the shortening of chromosomes over time to a romance’s gradual entropy; “We Will Die Beautifully in the Way of Stars” thinks ahead to the two lovers’ deaths at the start of their affair; “The Plural of Us” declares that “the end of us an us/is a death/without dying”; “Magnificent Things” praises a lover’s consoling presence, then confesses, “Already I miss you,/not as you are but a future/in which you are not. Inevitable.” It is not difficult to surmise why the poet’s grief takes the form of dread. She herself is all too aware of why love and death go together in her mind: “In the dark, I rehearse/my slow waltz with loss./I know the steps by heart.” A new love, whether that of a friend or a lover, is another potential future loss, another focal point around which to concentrate her sorrows.

But if Qi thinks that love entails inevitable loss, then she also thinks that being in loving relations with others (whatever form these may take) is just as inevitable. “Biology Lesson 1” draws a poetic inference from cell behavior: “Cells need touch–/isolated cells wither,/float away/in a blood-red sea.” Grief craves solitude. Yet, if the griever gets the radical privacy she seeks, she will literally lose her life. Lest we infer that Qi views love as an unqualified good, though, we should study “Biology Lesson 2”: “Too much touch/stifles. Even the toughest/cells die wanting/room to breathe.” We can only survive when we bind ourselves to other people through various affections and duties. Yet solidarity is a crowd. Sympathies, obligations, commitments distract us from the task of dealing with our own pain. This paradox, at once biological and ethical, rears its head throughout Focal Point. Other people impinge upon the poet’s privacy incessantly: the father who, grappling with his own sadness, leans on his loyal daughter for guidance; the friend who, trying to say the right thing, offers one too many sympathies instead of leaving well alone. People pressure the poet to mourn, to share her private grief in public rituals. Much of the time, she just wants to be left alone, as in “Cactus Heart,” where she imagines hoarding water in the desert by herself, surviving on her own strength. Sometimes, though, as in “Magnificent Things,” she admits that the only thing that can warm her back to vitality is another human’s embrace. The difficulty here is that, in order for private grieving to become public mourning, she has to let others partake of the singular relationship she had with her mother, let them project their own perspectives onto her most sacred memories. Love necessitates that she share her bereavement with others, but it seems quite possible, at times, that love demands more than she is able to give.

That said, Qi recognizes that love entails more than just giving away one’s privacy. Love also means carrying other people’s griefs. It means coming to her distraught father’s aid by assuming medical power of attorney for her mother. It means tending to friends who are “in love, in tears, in the closet, in danger.” Again, it is possible that love asks her to shoulder more than she is able to. But in the course of opening herself up to others’ sympathies and sympathizing with them in turn, she becomes increasingly focused on more public objects – social problems such as anti-Asian racism, economic inequality, COVID-19, mass shootings. In the book’s final division, Qi scales up grief’s scope to encompass not only herself and her loved ones but the entire ailing world. In “Contingencies,” for example, Qi turns her focus to another bereaved mother, an earth–mother who is dying of ecocide, her forests and cities ashed by runaway fires. “Everywhere somewhere is burning/and it’s too late to look back,” she laments. “I want to move the mountains and breathe,/which is to say I want to be anywhere but here.” Again, Qi sees no way out of grief’s clutches. If indeed we learn something from grief, it is how to scale it up, from the personal to the social, from the ailing individual to the ailing society, from our own particular mothers to our common earth-mother. From grief we learn how to mourn.

In her classic essay On Being Ill, Virginia Woolf observes that illness reveals truths that are imperceptible in times of wellness. When we fall ill, we let ourselves temporarily desert “the army of the upright,” permit ourselves to be “irresponsible and disinterested and able, perhaps for the first time in years, to look up–for example, at the sky.” Were we to substitute the words “grief” and “loss” for “illness” in Woolf’s essay, we would have an accurate summation of Focal Point. The book’s cover, designed by Hilary Steinberg, shows a smoke- and ash-filled sky burning orange with a sunset and the afterglow of a wildfire. Do we see this sky when we look up? What are we to do with these ashes? How are we to mourn on this scale? Graciously, Qi’s formidable first collection does not leave us with any of the usual pat answers on which our loss-averse culture has grown so dependent. Instead, as California burns and thousands fall ill and die from a resurgent pandemic, her poems inspire us to look up at the sky and, perhaps for the first time, to focus on the questions themselves.

Kelly M.S. Swope is Visiting Professor of Philosophy at Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio, where he lectures in political philosophy. He hails from Granville, Ohio.

This post may contain affiliate links.