You might call it the Holy Grail of our soul, that which we call identity. Some are confident as to who and what they are while others struggle their whole lives with the question. Then there are those who are un-satisfied with who they are and wish to be someone else. In his four chapter essay, Giving up the Ghost, published recently on the Hazlitt online site, Brin-Jonathan Butler, a self-described “tourist of himself,” attacks the question on a number of levels from a discussion of Antionino’s 1975 film with Jack Nicholson, The Passenger, to the death of Anthony Bourdain and filtered once again through past relationships. The result is engaging and thought provoking as only Butler can write.

If you have not seen The Passenger or viewed it since it came out, it is the perfect film to spark a conversation about identity. In it, Jack Nicholson exchanges identities with a man who dies in a hotel room next to him. Nicholson’s character, David Locke, declares himself dead after switching papers with the deceased neighbor. The setting is in the Sahara, in northern Chad. Locke doesn’t know he has just assumed the identity of an arms dealer. As he pieces together the life of the dead man, he watches from afar his family’s reaction to his death, and in the process begins to take a look at who he is or rather, who he was. It is indeed a great film to obsess over as the implications morph in your mind long after watching it. Identity can be a bitch.

Brin-Jonathan Butler is the author The Domino Diaries a memoir about Cuba and boxing and The Grand Master: Magnus Carlsen and the Match that Made Chess Great Again. His writing has appeared in many periodicals including The Paris Review, Harpers, ESPN The Magazine, amongst others.

We chatted online recently about the above topics to get to the bottom of things. Join us.

David Breithaupt: You write that we are attracted to stories that we identify with, what drew you to The Passenger?

Brin-Jonathan Butler: What profoundly drew me to The Passenger and identifying with the protagonist David Locke specifically was the overwhelming feeling of being miscast in your own life. Orson Welles repeated many times that the greatest things in movies are “divine accidents” and one must preside over them, beautiful accidents that keep films from being dead. I’m not sure why Welles restricted this thinking to directing films when it seems to apply to many aspects of being alive as well. All my life people have reminded me that I know them — “you know me” — and it accomplishes exactly the opposite. From acquaintances, friends, partners, family–-–it always serves to remind me of the mystery we all are to each other and to ourselves. It reminds me how limited and prosaic our best satellites are to bring back meaningful information from each others’ worlds. And while many people struggle to reconcile their contradictions and achieve some semblance of consistency with who they are, The Passenger reminds us that we’re capable, if we’re open to it, of living many lives and being many selves within them. Every mask and every lie inevitably points at the truth. And if The Passenger is a fairytale of some variety, like all the best fairytales the moral seems absent. And the more times I engage with the film it reminds me of something Lewis Carrol said about Through The Looking Glass, “We are but older children, dear, Who fret to find our bedtime near.”

You have a great story in your piece about obtaining Jack Nicholson’s phone number and finally reaching him. Could you talk a little about what that was like?

So much of this game, when I finally made some sense of it for myself, seems to come down to three basic things: find your way into the rooms you want to enter; find a reason to remain in those rooms; find a reason to be invited back. With Nicholson, my dream objective was to watch The Passenger with him at his Mulholland Drive residence in Los Angeles. I failed at this. But the whole thing began with this kind of Big Lebowski-like situation of getting his private phone number. Weirdly enough, my journalism career began when Freddie Roach gave me Mike Tyson’s phone number. That took over 140 calls over the next month between me and Tyson’s assistant to finally get the go-ahead to fly down to Las Vegas for an interview at a major hotel. The problem that occurred when I showed up at the hotel and asked the staff about entering the room for our interview is they had no idea who I was or anything to do with the interview. I was not having a good day at that point. But at the last second, Tyson’s assistant answered the phone and gave me the address to the house and an hour later I walked through the door and Tyson asked, “How did this white motherfucker get in my living room?”

Nicholson did not answer the phone when I finally worked up the nerve to call. His assistant did. And she was very kind and patient with me before basically dropping the axe that there was no way in hell he was ever going to talk to me. Everything I tried to pry my way into an impossible situation failed demonstrably. But I was trying everything I could to sound professional. I wanted some kind of professional justification and of course I had none. But instead of her hanging up on me, she dropped her guard and took pity. When I heard the real person on the other end of the line I leveled with her about how much I’d really just wanted to talk to Nicholson about our unlikely, shared favorite film, The Passenger. That changed everything. In a way the actual phone call with Nicholson felt a bit like an audio version of what Antonioni does visually with the viewer…the barriers and confusion. There was construction going on in the Spanish Harlem apartment next to me. Nicholson’s windchimes were very loud in his backyard. Our connection on the line wasn’t great. Life intruded. But I don’t have high expectations that I’ll conduct a more personally meaningful cold call for the remainder of my life. And the fact that his first words to me was to offer that he didn’t give any interviews just before I was explicitly intending to conduct one with him, still makes me smile.

A few months ago I traveled to Los Angeles and hiked up from Hollywood to Mulholland Drive where there’s a little clearing overlooking the city next to Nicholson’s property. He’s lived there since he bought it right after making Easy Rider. It’s a remarkably serene location and feels at once very isolated despite being maybe 20 minutes drive from Sunset Boulevard. On the side of the road you can’t see anything behind all the foliage and trees obscuring Nicholson’s residence, but several large birds were circling directly in front of his panoramic view. His assistant told me he likes to walk out to his backyard with a favorite book and just spend the day reading it cover to cover. I was wondering if the 84-year-old guy had lumbered over that afternoon and what he might be reading on that particular day.

You have a great line (one of many) toward the end of your piece from Oliver Wendell Holmes about how many of us go to the grave with the music inside us un-played. Is this mythologizing of ourselves, the struggle with identity, maybe an attempt to find that music?

It’s such a good question. Because I think we start off almost totally incapable of not mythologizing everything and everyone around us and then, a bit like Alice, trying to reverse engineer our own role in the story and also what the story is supposed to be and how much agency we have to push back against whoever or whatever is engineered it. I remember my first day of kindergarten and we were organized into a circle for morning attendance and as the teacher went down her list calling out names I was trying to diagnose who had the most power in the room. Throughout that day I continued trying to track this down. The most beautiful girl, the funniest person, the strongest boy, the most intelligent person, the most socially gifted, the spookiest person, the most dangerous, etc. At the end of the day we were asked to paint an elephant and, by far, the most talented artist in the class was also the only kid who didn’t bother to collect his elephant to bring it home to their parents. Both acts, the art he produced and his utter disdain at keeping it mesmerized the class more than any other action or personality or demonstration of who anyone was that day. The artist had the most power. And I think about this often when Rembrandt’s work deals with so many businessmen attempting to usurp power as the most important people of their day with poses like conquerors. But today we have no idea who any of these Dutch businessmen were, only that Rembrandt depicted them. Whatever importance they wielded in their day has washed away like a sandcastle and the artist’s brief encounter with them is all we really care about now.

The artist who painted the elephant that first day of kindergarten became my best friend many years later who suggested I send along my letter to his editor friend with an accompanying note that I’d taken my life after writing it. Also, when he rejected his own painted elephant because it was beneath his five-year-old artist standards, I quietly asked the teacher if I could take it home if he didn’t want it. I then threw away my horrible painted elephant and offered the brilliant discarded painted elephant to my mother and I vividly recall her declaring I was meant to be an artist when she saw it and put it up on her wall.

Velasquez and Goya come to mind as the first court painters who strove to reveal their patrons as they truly were, not who they wanted to be. In the process, they were profoundly talented enough to capture their spirit and not just their actual likeness. How dangerous is it to hold up that kind of mirror to another person?

Well, you’ve picked out the two painters I’ve spent the most time with at the Prado, my favorite museum in the world. “Las Meninas” was painted in 1656 and only seems to have gained complexity and enigmatic majesty as it closes in on its 400th birthday. Yet what is crystal clear about it is the fact that its depiction of Philip IV and his wife could have instantly resulted in the king having Velázquez executed. Historically, beyond the jester or the poet, who was allowed to tell the king the truth in his court? The ambiguity of Goya’s intentions behind so many of his portraits has also always fascinated me. Robert Hughes has been one of my favorite writers since I found him maybe 15 years ago and through a happy accident we both have Goya as our all time favorite artist.

I’m not sure holding up a mirror to an individual goes over any better than holding up a mirror to a culture or a faith but both the artists you mentioned certainly did that. Goya’s “The Third of May 1808” wasn’t the result of reporting anymore than Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest or Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels was, but it exposed dark truths with more illumination than anything else on offer. South Park’s creators have made the point that it’s incredibly hard to satirize American culture given that they see it as constitutionally incapable of shame. I like the idea that in South Park’s world there are only children and adults, no teenagers, the only teenager is American society itself supplying the punch lines and backdrops. Such a curious society where in 1951, J.D. Salinger was the first artist to present a teenaged character that made America, along with 75 million readers around the world after it, question for the first time if a teenager knew something adult society didn’t.

I think at the heart of the piece I wrote exploring a rogues gallery of extremely potent characters in literature and painting who took their own lives, I wanted to hold up the haunting ambiguity of suicide within the human condition. Nearly every mainstream suicide becomes a bizarre kind of referendum of whether the act required courage or cowardice. As Kundera said about vertigo, the most acutely frightening aspect is not being pulled over the edge but our desire for that edge. The suicide rate in America is triple the homicide rate and that’s before factoring in deaths of despair or even taking into account how underreported suicide is. I think why we’re so drawn and fetishize murder and serial killers as the lowest common denominator of shallow, mass entertainment speaks to the essence of security: an obsession with the intruder. Suicide, by contrast, forces us to ask questions and confront a sea of uncertainty. Why is it, as the only species capable of higher reasoning on the planet, do we function more like a virus in terms of our impact? Why does our sense of self-preservation, confronted with such overwhelming damning evidence about the consequences of our actions never seem to kick in? More people believe in bigfoot than the big bang theory and angels than climate change. People loved the scene from The Matrix where you’re presented with the red or blue pill, but as Zizek pointed out:

“The choice between the blue and the red pill is not really a choice between illusion and reality. Of course, the Matrix is a machine for fictions, but these are fictions which already structure our reality. If you take away from our reality the symbolic fictions that regulate it, you lose reality itself.”

So I guess holding up the mirror presents us with asking for the third pill, whatever the hell that is.

Yes, you do have a rogues gallery of flame outs and suicides and I wonder if there is a common thread, maybe a disintegrating pool patio that made them all collapse? While thinking about this, I came across this thought from James Baldwin in his No Name in the Street. He wrote “But I have always been struck, in America, by an emotional poverty so bottomless, and a terror of human life, of human touch, so deep, that virtually no American appears able to achieve any viable, organic connection between his public stance and his private life.” What is the end result of such an existence?

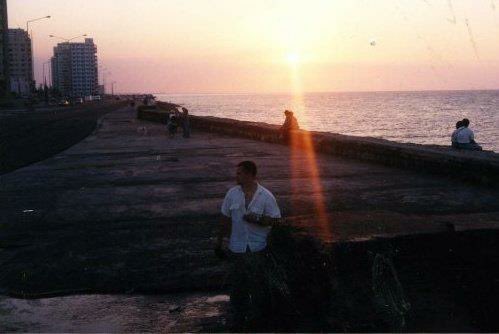

It was a profoundly spooky sensation after living in America for a few years that whenever I’d arrive at the international section of an airport it was completely irrelevant where I was going, but I immediately experienced 85% of my anxiety and stress level evaporate. I spent a decade on-and-off living in Havana, Cuba and before arrival you receive endless warnings about the desperation and poverty you’ll encounter. And there certainly was. What I was not warned about, was the mirror it held up to many other forms of poverty in where I’d come from: I had no sense of community, my neighbors were strangers, homes were doubling in size with families shrinking to half in number of the previous generation, happiness and success had mostly been defined through materialistic acquisition, there was an incredible poverty of spirit I hadn’t even known existed. A bit like David Foster Wallace’s example about the fish and water, “What the hell is water?” anecdote. It’s a bit like the bait-and-switch of beginning the journey with Tony Soprano, you think you can safely explore his hypocrisy and Faustian bargain at a distance to supply himself and his family with all the material comforts in the world at the expense of having no reliable center, but very quickly––as was the case with Goodfellas, Casino, and Wolf Of Wall Street––we’re looking at America and aspects of every “normal” family you know confronting gradations of the same dynamic. We touched on suicide earlier in American society, but in terms of what is required for most Americans to emotionally cope with regular day-to-day life, it’s beyond extreme the crutches that are required: alcohol, drugs, pharmaceuticals, work addiction, sex addiction, social media transforming us all into publicists on behalf of the commodification of our lives and prostituting the most sacred aspects of it often to unknown eyes. In weird way, I find all of this actually quite life affirming and in some may makes me rejoice about humanity. What I mean by that is if you could buy your way into happiness and joy and contentment, the richest society in human history would be an example of that philosophy bearing out its hypothesis. Instead, what we have, exposes the flaws and fundamental fallacy. Think of the accounting of any meaningful legacy, all of the lives that uplift our collective spirit have one thing in common: they are defined not by what they had, but by what they gave.

I remember first arriving in Havana and trying to acclimate to the fact that there was no advertising in Cuba beyond the ubiquitous propaganda of the state. Most of that hysteria manifests in instructing people to go beyond human nature and think of others ahead of yourself. There’s a recognition of our design as intrinsically selfish until we learn about compassion for others. Every child wants a second toy for themselves before they see any value in sharing with anyone else. But in America you have the overwhelming perversity of our system attempting to alleviate any guilt for giving into our most selfish desires. Any consequences for giving in always seem to be dealt with breathtaking lengths of denial. They only real sin in America is not having an unquenchable desire. Essentially arriving at contentment is the biggest nightmare. I had a telemarketer call me once and I accidentally picked up the phone, “Can I talk to you about your boxing training and how we can increase your clients and income?” I turned over how I was feeling that particular day and told him I was actually happy with my number of clients and content with my income. There was just silence for about 10 seconds. He didn’t know what to say.

This is such a bottomless topic and made even worse given I spent several hours a few weeks ago rewatching Adam Curtis’ documentary Century of the Self and Freud’s nephew Edward Bernays transforming the country using Uncle Siggy’s tools to transform us all from citizens into consumers. The other side of worshipping individuality as the ultimate value is just how fucking lonely it is the more you succeed. Both poles of our society’s pecking order resemble each other in a fashion: Howard Hughes in his version of solitary confinement vs. our country having more people in jail than anywhere else on earth and using solitary confinement as the harshest legal punishment. Working backwards from that idea, is simply being soberly alone with your thoughts the ultimate punishment anyone can imagine for themselves?

Have these ruminations taken a toll during the pandemic lock down in the US? Or have we enlightened ourselves?

For me the most disturbing realization after this long contending with the pandemic and where we seem to be currently is the abiding feeling that there’s no middle ground anymore. Instead of a tragedy assisting us in coming together, this corrosive balkanization just seems to get worse and worse. If masks or vaccines are contentious, I’m not really clear why traffic lights aren’t also. Why aren’t we relitigating safety belts on the basis of them being some harbinger of a dictatorship? Even up to the early 1980s, we had about 14% of Americans regularly wearing them. Safety-belts. I’m not really clear what kind of mass shooting is required to persuade gun lovers to even consider modest reform. America could give birth to the greatest human ever born capable of solving every dilemma on earth and if they declared themselves an atheist he couldn’t anywhere near political power. It’s a lot harder to declare war on climate change than on drugs or terrorism. The Big Bang Theory is about as believed in as Big Foot. It all kinda reminds me of Kafka on his death bed being confronted by his friend for having a lack of hope. He corrected this assessment, he had hope, “just not for us.”

Then again, I think Fred Rogers was onto something, rather his mother was onto something, when she told him that with any tragedy or circumstances that confronts you with despair, “look for the helpers.” And there always are, no matter how dire the situation or predicament or the odds.

David Breithaupt has written for The Nervous Breakdown, Rumpus, Exquisite Corpse, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and others. He has worked as a bibliographic assistant to Allen Ginsberg, a newsstand checker for Rolling Stone, and a staff member to the great Brazenhead Bookstore in New York City. He currently works for two sports newspapers in Columbus, Ohio, covering the Cincinnati Reds and OSU collegiate sports. Recent writing can be found in One Last Lunch: A Final Meal With Those Who Meant So Much To Us, The Columbus Anthology, and on Storgy.

This post may contain affiliate links.