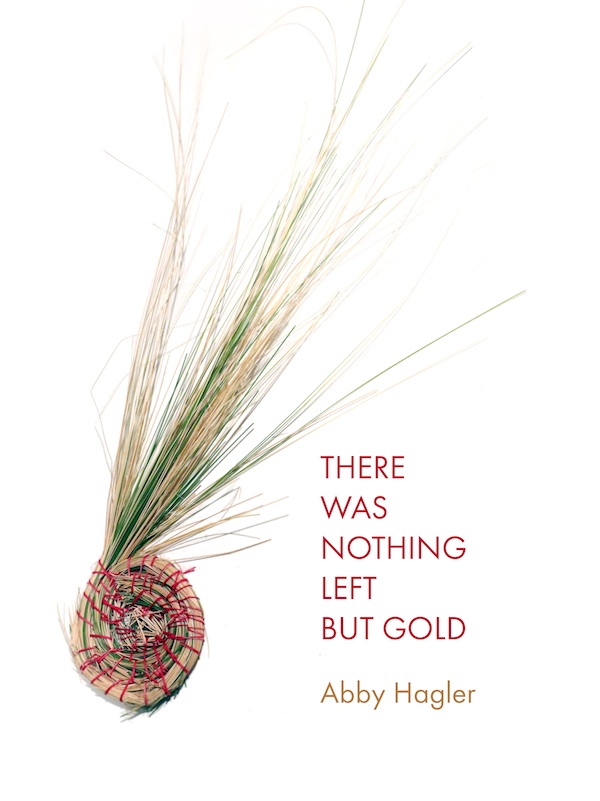

The following is an excerpt from There Was Nothing Left But Gold (Essay Press, 2021), published with permission of the publisher.

I am not a runaway. I am an adult driving through my home state of Nebraska. Someone at a dinner party once joked to me, If you grew up in a small town and you got out, you deserve a medal. Which is to say, I am not not running away either. Call it sneaking out by walking backwards. In a dream from childhood, I could jump high in the air and stay there. Call it circling, maybe like a carrion bird. Or hovering over a page the way I do when reading about mysterious drones flying over my mother’s house, coming from Colorado.

Call it haunting. Adulthood will do that—incline you to become the blank space in the doorway. This time, I am not absenting myself from any family gathering so much as ghosting over fields and blacktop, Nebraska and farmers and gas stations once familiar to me decades ago. Call it an inventory in the form of what appears in the mirror of a compact car from which I whisper, I’m still here. To say that is, I suppose, how I ended up in Red Cloud.

Red Cloud is Willa Cather’s girlhood home. This visit is not about her, though I am aware she once admitted in a letter, “I seem fated to send people on journeys.” Readers wanted to see the landscapes her stories reveled in. In this spirit, I packed one of her novels from the Nebraska trilogy, Song of the Lark. The story centers on an artistic girl named Thea Kronborg, a first-generation Swede from a small town called Moonstone. The plot is her struggle to separate herself from her birthplace in order to grow as a musician. Cather herself would move on from Red Cloud to attend college at the University of Nebraska in the early 1900s —an impressive feat. She quit the Midwest for good soon after by accepting an editorship at McClure’s magazine on the east coast.

I doubt any of her visits back to Nebraska were as aimless as this. For one thing, she was not the type to consider herself a ghost. But I am, so I putter west on I-80 in a four-cylinder Kia with no intention of seeing family. This route could easily take me to my mother, who lives in the Sandhills, where I grew up. Instead, I flick the blinker, exit south toward Hastings.

My Nebraska is tinted blue. It always will be. Sunlight is stronger here somehow. It is difficult for my eyes to adjust to this level of bright. When I lived here, I wore BluBlockers—known by optometrists as sleep glasses–to mitigate the hazy distortion of blue light while driving. These glasses are also hilariously big. In truth, I have always been addicted to the view they provide: a world gone completely gold.

Whenever I stop to stretch, or walk, or journal, something alarmingly clear is that I feel recognition and deep memories weltering like crop rows going fallow. However, I do not feel nostalgia for Nebraska.

Nostalgia, when it was first defined, was a type of illness. Svetlana Boym notes in her book The Future of Nostalgia that it was classified in 1688 by a physician named Johannes Hofer as a type of cognitive ailment. Most articles will remind you that nostalgia comes from the Greek nostos meaning “return” and algos meaning “pain,” which in turn makes me think of the Spanish words nosotros meaning “we” and algo meaning “something/anything.” Our thing.

Physicians from the seventeenth into the nineteenth century believed in a panoply of cures from opium to leeches. Travel was recommended not as a physical tonic but as a way to bring the mind into the present tense. A cure became the search for how to actualize distance between the body and its past. The premise of Boym’s book casts a wide net over time and place by positing a collective nostalgia with the question: “Can we be nostalgic for the home we never had?” On this voyage, I have to ask myself: Can I be nostalgic for a home where I no longer belong?

If anything, I have made myself a stranger by staying away despite the fact that I can still picture how each season looks laid upon the ditches. It’s possible I’ve been gone so long that everything is nostalgic—the gray cement courthouses, the low red-brick high schools, the dusty little tree strips stitching the ground.

The passenger seat of my car is piled with books on Marxism, divination, tall tales, and myths the Baptist women who attended my great-grandmother’s card parties surely would have condemned. There is no one who can tell me what to do anymore—one benefit of invisibility. In mind, I carry a quote from Spectres of Marx regarding Derrida’s term hauntology. It describes the lifecycle of an idea. He, like Marx and Engels, believed Communism would “haunt Western society from beyond the grave.”

What haunts is a thought, one crossing people’s minds whether or not the word was even breathed aloud. Haunting occurs as the color of daylight in even the haziest memory. Childhood haunts, revisiting in the choice words used against a current lover, in how quickly a fever is dealt with, or the curve the neck assumes when the body needs to cry.

To Derrida, hauntology is about unnoticed return, invisible lingering. He bases it on Hamlet’s meditation of time being out of joint, a son’s lament regarding the unexpected death of his father. I can’t help but notice that the cork was not placed in Hamlet’s lineage, as hauntology critics will say. Instead, this death stoppered an even smaller claim on which Hamlet staked his entire life – his connection to family overall. He no longer saw his mother or uncle as his extension. Family members are, for many of us, the first witnesses to our very existence. Each member holds our history in their own lived-in muscle and memory.

I am without stake. Not due to weak stock but because I come from people who have trouble with love. My history is littered with hang-ups and years without speaking. Shame over the inability to buy gifts for people I can’t get to know. Soured dinners. Slaps. Thrown wrenches. Lockouts. Leaving the vacation early to escape an argument. Pretending not to have heard the outburst. Types of silence, all of them. Acts that swallow a conversation. Communication dropped off completely with my brother and my mother over politics. It never picked up with their spouses or children, leaving me to wonder if relationships are space to claim after all. At home as I am among these roads and fields, I wonder: Who am I if I no longer wish to speak to my family?

Who am I when they speak of me? In my mother’s version of my story, I am living the tale of a sad, unmarried woman. Sometimes I wonder if my narrative is one single line or if it works like a river, pushed by wind and land, cutting off its own limbs, changing course due to the wills of men.

—

Winter urged something in Cather. Each of her prairie novels begins with it in mind: a sense of foreboding, a change of season mere pages in. A hurt animal. The steel slab sky lowering over a patchwork town. One parent not long for this world. The dread that influences an out-of-season tourist to visit Red Cloud, which feels the same as a reader living in a novel they never wanted to read.

The last breath of many novels is a pinpoint of night that grows large, a head held against a stomach, an eye squinting open or closed. In O Pioneers! Cather leaves off toward sunset “on a brilliant October day” in the aftermath of a double homicide, in the glow of awkward forgiveness. My Ántonia concludes in early evening on a road cradled by “rough pastures” twenty years in the future, where hurt does not loiter. Song of the Lark reaches for silence as “the sky was still flaming the last rays of sun that was sinking,” hushed in the midst of the imagined future of Thea’s hometown carrying on without her.

In Nebraska, snow forces the landscape to stop speaking as men do to rivers, as adults do to children. Movement toward silence is one motivation of narrative. Running toward the moment when the voice has spun out of story is cathartic. Upon viewing Red Cloud all around me, I think for a moment this is my purpose here as well.

But ghosting does not work like that. It is a loop, the river’s elbow forming its own lake with cattails and moss and trapped fish. It takes root like a small town and spreads its rooftops. A haunting has no timeline. It is a book that is written, then taken apart. A structure in which it is easy to continue to wander, like the tallgrass itself. Haunting is the competition between the need to speak and someone else’s need for you to stay quiet.

On the page of a novel, silence is its own season. It ends and begins again—perennial. A system of borders to speech, however violently wrought. At 80 miles per hour on the interstate, time passes unnoticed. Like ancient grass, I am always here, where I began my life, with nowhere left to go but away. On the page, silence encompasses time for the narrator to breathe. There, the reader thinks. I drive knowing white space is a simple distance, an enormous claim staked without compromise, much like the state of Nebraska itself.

—

When my mother and I are on good terms, she speaks most often to her fears: of a daughter who never goes to church, who proclaims herself a feminist— college-educated with no kids, no car, no house, no yard.

When I adopted a cat, I heard her say, Cats smother infants. Every time I smoke weed, I imagine it incinerating an egg inside my fallopian tube as she says marijuana does. A poisonous snake will have a diamond shape on its head, she stated to my brother and his fellow Webelos making crafts at our big brown dinner table. This is not true of rattlesnakes, the only venomous serpent in the state. I look up the facts, get better at evaluating sources, burn fertility. My anger—the part of me that viciously loves myself – saves dozens upon dozens of links to news, history, and scientific findings. I will never send them.

Trauma has an afterlife sometimes in the form of a fear, sometimes in the form of a cure. Both are built around pain endured even if the original speaker or the back story is lost. Pain works like haunting. Fear lasts longer than physical pain, longer than the belief in any cure.

When my mother and I talk, it is not long before we must talk about the past. This is always how she has shown closeness to me—to talk about her own upbringing in poverty, her own failing marriage, and the pain of my grandmothers and my great grandmothers inside their marriages. We used to drive past the old blacksmith gateway wrought to read MACH that once belonged to my mother’s grandparents. It now protects a vacant hill.

In my twenties, on one of these drives, I said, bluntly, Your child is not your therapist. And since, there has been less talk of my grandfather pulling the trigger on the rifle held to his stomach. Of my father leaving my mother for other women. Of her two older sisters who were killed by my grandmother’s Pentecostal fear of modern medicine. What women in my family have whispered just before they died. Knowledge becomes a kind of aftermath.

She used to say, Salt a cut to help it heal. It came from the meat packing plant where she took shifts in high school. I have seen her doing this, pouring table salt from the lip of the box onto her finger until all the blood absorbed. See my hands? No scars. But all I could see was the wound and a remedy that seemed to increase the original pain.

When I told her I wanted to go to graduate school, we were driving past those blacksmith gates. She said, I don’t know how to help you anymore, and didn’t look away from the windshield.

I realized her helplessness. She had never really been single. Never written an academic paper, gone to a conference, or been part of a union. She’d never freelanced or commuted via public transportation. In college, my parents receded a little more as I advanced through each year. It was on that day when I realized my parents had given me the means to pursue my dreams and it had made me a stranger.

—

This whole time spent avoiding where I grew up, I am certain that it is possible to leave a place but the sound of it spoken aloud will stay inside me like a name I’ve been called since birth. On the highway a few hours from my mother’s house, I wondered if Nebraska thundered in Cather the way it does for me.

“Reckoning with ghosts is not like deciding to read a book; you cannot choose the ghosts with which you are willing to engage,” Avery Gordon says about those who are haunted in Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. This prairie did not ask me to revisit. Maybe I am the one who is out of joint in choosing this place instead of the unknown.

In truth, I have been gone so long I chose Cather’s girlhood home over my own because I feel more welcome as a stranger here than as a stranger there. Worrying about time travel and old hurts and soil at the curve, it becomes clear how long it has been since I have seen grass. Prairie is a strange body that puts on a performance of water. It ripples and waves, spits bones back to the surface, covers teeth and limbs of tiny predators. Perhaps grass moves like this because it haunts the ocean that covered the land millions of years ago, its roots proliferating from the water’s silt reminder. Perhaps grass haunts water as people undoubtedly come to haunt their own pasts.

—

The Willa Cather Museum spans many buildings around town, all of which contain nothing of what I want from this novel. Nothing of what I want from Nebraska. Nothing that feels like family. It is one of the only functioning businesses in downtown Red Cloud. It is a memorial to the fact that people left and never came back. This silence is my story too, I want to blurt to the docent at the entrance before winding through the bookstore into a side room displaying small tables arranged in a timeline of Cather’s life. I have also left a house and cottonwoods, a parent, and a road on which I’ve realized myself over and over again.

Patches of tallgrass are trimmed next to the roads in Red Cloud. The trees are cut back too, no longer holding down soil. I whisper this fact while pushing the biography titled Willa Cather: Double Lives under my arm. The few possessions of Cather’s that the Museum has include first edition books, gloves, tiny toys, a five-year-old’s white church dress, shoes: mostly childhood things.

Moving away from a place requires abandonment of certain objects—proof of existence. Possessions are the placeholders of existing in the present. Your own remnants come to compose your face more than your face. What haunts are those who wonder how steadily you breathe while sleeping, those who still imagine you might show up to dinner in their dreams.

Out loud, the cashier laments the enormous portraits on display. They are apparently untrue to who Cather really was. We just don’t have any good pictures of Willa’s eyes, she tells me while offering the receipt, making sure I leave with a detail to remember. I want you to know, she had such beautiful green eyes.

Thumbing through Double Lives, I scan the chapter titled “Buried Alive.” This is how Cather said she felt growing up in Nebraska. It seems she always struggled with loving this state. In an essay titled “My First Novels (there were two)”, she regretted Song of the Lark. She wrote that both Song and Alexander’s Bridge have weak storylines and flimsy characters due to her attempt to fit in among popular novelists.

It’s clear these novels positioned her to write O Pioneers! and My Ántonia, which Cather posited as her first two real novels. They are the novels that uplift the landscape and draw fewer character sketches of overt racists, older men wanting to marry pre-teen girls, hypocritical Methodists, and waffling feminist heroines.

In the middle, Thea’s choice to leave Moonstone is justified with Cather’s typical hubris tinged by bitterness. “Artistic growth is, more than anything else, a refining of the sense of truthfulness,” the narrator declares. “The stupid believe that to be truthful is easy; only the artist, the great artist, knows how difficult it is.”

“My First Novels” also ignores two other prior publications on display in Cather’s museum—a slim volume of poems and a friendly-looking collection of short stories titled The Troll Garden. Lee says The Troll Garden stories were “written out of a deep rage at the obstruction of the artist.” I can see the parallel between the angry narrator of these stories and the one in Song of the Lark. In a letter to Owen Jones, Cather blamed Nebraska for the narrative tone. She said the writing was motivated by the “raging bad temper” of an artist thwarted by her own environment. It is undeniable that Cather’s success was built upon that anger. The hurt of an outsider who once belonged. The voice hovering over a border.

This post may contain affiliate links.