This essay was first made available last month, exclusively for our Patreon supporters. If you want to support Full Stop’s original literary criticism, please consider becoming a Patreon supporter.

“Everything is a deathly flower,” writes Maneo Mohale, in their poem of the same name, and from another poem, in another book, Kopano Maroga calls back: “These things are deathly.”

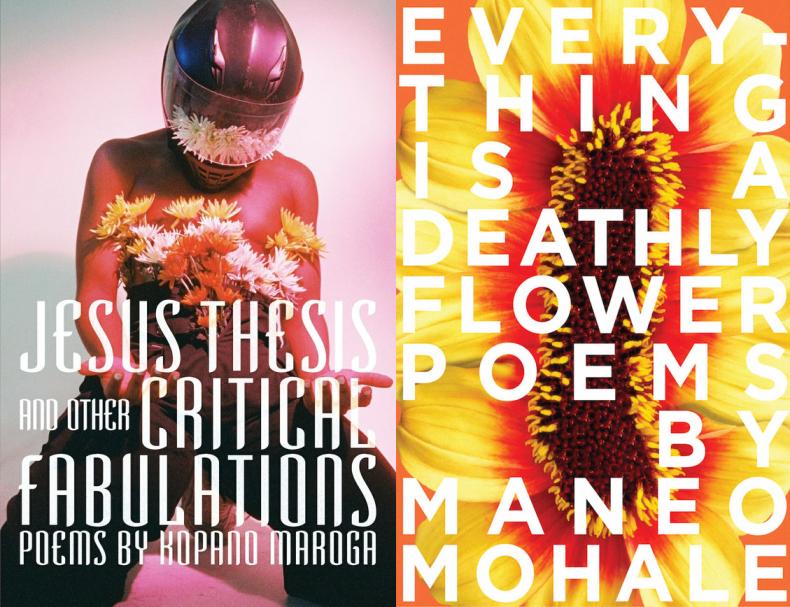

It was, perhaps, an obvious choice to read Kopano Maroga’s Jesus Thesis and other Critical Fabulations and Maneo Mohale’s Everything Is a Deathly Flower together. They are, after all, friends and collaborators. Their collections were published within a year of each other by the same small press, uHlanga. They were, as it happens, both born in the same Gauteng suburb, Benoni. Both represent a South African poetic canon which is becoming increasingly (and at long last) enriched by Black, queer voices. And both have written books around trauma.

The trauma at the core of Mohale’s book is rape, although the poet never calls it that. They develop many other words for violation. It is “a striped pole in the middle of the ocean.” It is a “yellow line.” It is “two tongues hiding in a mine dump.” It is “a gulping thing.” It is “something awful.” It is “this room,” “this moment,” “the memory,” or simply, “four words.” Most often, Mohale refers to the traumatic event as “the night-room.” Maroga does a similar thing where they come up with all kinds of new names for body: “a nest of glass,” “an ocean,” “a sepulcher,” “an armoire of fine china,” “a cliff face,” “a monument,” “all static,” “all rumbling sky,” “a placeholder,” “a metaphor,” “a stem,” “some thorns,” “a holding cell for silence.”

These names might seem like euphemisms, hiding the event from the reader’s view. Indeed, Mohale is avoiding something, and it’s not so much the reader as it is being read. To be read, for the victim, is to be violated anew. In the titular poem of this collection, Mohale writes:

You read my silence as Permission. You read my closed eyes as Assent. And my turned head as Of Course I am Black and Woman and Queer What Else Could My Body Be For But Entry How Else Am I Legible But As Safe To Violate

Of course, to avoid being read is a complicated ordeal for a poet, as they later admit: “I am aware of the boisterous fizzy market for trauma.” They would rather come up with sixteen new names for victim (which they do in their poem “16 Days of Atavism”) than reveal their wound before a jury. Mohale withholds testimony, finds a backdoor way to talk about the event. To put it another way, if Mohale’s work dances around a silence, it might be because the silence cannot be named. We know that a threshold was crossed because Mohale tells us so in “Lobelia (Take a Seat),” and we know that there was a morning after (“Nemesia (Well, Thank You)”). But the night-room itself is empty, silent. It is as though the poem were ripped in half as Mohale tore the night-room out of it, “separat[ing] stem from stamen… fingers from flesh… stigma from style.” The poem is “dissected,” or, “d i s a s s o c i a t e d,” and the letters on the page perform this shearing off by pulling away from each other. The speaker, in this poem, is split down the middle into we. Two wes, one which says, “we are here,” and the other which says, “we are leaving;” one which says “this is history” (past) and the other, “this is memory” (present). As it sits couched between the poem about the crossed threshold and the morning after, “Night Jasmine” is the best picture we get of the night-room, and it is largely fragmented, scattered, unpindownable. Almost unreal:

separate stem from stamen fragmented safely, lifted

separate fingers from flesh separate stigma from style

[…]night jasmine already wilting

white with nectar wet

Another way to describe the shape of this poem is that it takes the form of a shell. One might also imagine it a bullet. Shell-shocked is a word that has gone out of fashion when talking about trauma. It has gone out of fashion because it is attached to soldiers, who are not the only victims in the story of trauma, whose wars are not the only wars waged. The more favored term, today, is post-traumatic stress disorder. But this neat, clinical phrase does not capture the shape of trauma, of the event which is both contained in time and resounds across it.

For Maroga and Mohale both, to write of trauma is to produce an echo. In Maroga’s “(don’t you know) even uncle tom gets the blues,” we find: “take your trauma / your trauma takes you… you or your trauma / your trauma or you.” A trigger is pulled, and time is pulled apart. The trigger is pulled, and time folds back in on itself. The past comes barreling into the present.

Mohale’s poem, “Hell & Peonies” is about being triggered in a lecture on war photography. The fifth canto reads:

in ink, as in rhetoric / war is a metaphor reserved for women, drugs and terror /mistakenly defanged / invoked on anniversaries of violence / as if its only / danger is on the page / or in the air / spat at us like teeth / war hides in the tendril / and the blue helmet / under the silken tie / in the shutter and / the shuddering pact / between / the optical / and the chemical / and the mechanical

Here the echo reverberates within the lines, “the shutter and the shuddering pact,” “the optical and the chemical and the mechanical.” The trauma in this case is not individual but generational: ships docked on stolen shores, shots fired centuries before. The report still sounds. It shakes out the ironies of an amnesiac present. “Peacekeepers,” in their blue helmets, carrying rifles. Capitalists, in their silken ties, thieving land and then some. Look closely, and all things seem to have been touched by someone’s pain—all things optical, chemical, mechanical. Everything blossoms in destruction, everything is a deathly flower.

Maroga’s poem “benediction” looks very much like Mohale’s “Night Jasmine.” An empty space, a seam of silence, divides the page in two. The poem begins strangely, as though it were a fragment: “and, in full bloom we wake to find / the dawn is still singing.” Where—when—did this enunciation begin? When did this “still singing” begin? This same “still” recurs in subsequent lines: “my mother calls and she is still weeping … the continents are still drifting.” The timescale of this poem conflates the tectonic and the human. Time is stretched to senselessness. There is no present or past, only an on-going.

In this way, these books get at another difficulty of representing trauma. Not only is it unnamable; it is also un-narratable. There is no possibility of plot, as Maroga’s “benediction” reminds us: “when the shores / meet / and when / they rupture / we call this a beginning.” A rupture is normally a climax, a breaking point which hurtles a story from middle to end. Here, the rupture catapults us back to the beginning. A traumatic event ruptures the middle of one’s story and can become the center of one’s life.

Maroga goes on: “we call this the river / and the river is a good teacher / for what it means to / never to go back / yet to always be / returning / we call this an / ending.” Again, the beginning, middle, and end of the story is ruptured by the dual motion of the river. The river never goes back; the river always returns. An ending that never ends joins a “still” that has no start. The poem ends with an “unblooming,” undoing the “full bloom” of the first line, and in so doing, ties the poem in a knot. As in, we might read this poem in a circle, with the last line bleeding into the first: we are an unblooming / in an orchard of fruit / too ripe for the harvest / and, in full bloom we wake to find / the dawn is still singing.” A benediction is typically uttered at a liturgy’s close; in Maroga’s benediction, the ending is the beginning is the ending.

The ouroborosian structure of “benediction” seems, to me, an attempt to heal this more complex dimension of trauma: not a wound but a web of wounds, connected across space, place, time. After all, to go back and forth is to rock, to cradle. To cradle a human life (a mother weeping) in one arm and the life of the land (continents, shores, rivers) in the other might be to heal a trauma ongoing. Mohale performs a similar maneuver in the line, “I’ll be a backward pilgrim up the canal & back to the first night-room.” Doubling back through time, the poet makes a pilgrimage to a site of grief before their own birth, and in so doing, traces a thread between night-rooms. The hope in this act of narrative stitching is that, if the poet manages to heal from one night-room, they can heal from them all.

But still, if it is difficult to speak about one’s own trauma without edging up against a silence, to speak about this greater woundedness might be near impossible. Maroga seems to agree. “Let it be known / there are no words lonely enough for / the estrangement of a body from its people / let it be known / we search for the words anyway.” A lonely voice, or a voice alone, will find no words. But then this we peers out from the sentence like a silver lining. It makes sense. When one can’t speak, it would help to join a chorus.

Mohale’s titular poem contains the following epigraph by Saeed Jones:

In place of no, my leaking mouth spills foxgloves.

Trumpets of tongued blossoms litter the locked closet.

Up to my ankles in petals, the hanged gowns close in,

Mother multiplied, more — there’s always more.

To include an epigraph before a poem is not unusual. What is special about this poem is that Mohale weaves Jones’ lines into their own, and transforms them:

I am

up to my ankles in petals, the hanged gowns close in

ensnaring you and suddenly I am safe.

[…]

Every petal that fell

from my mouth is a survivor, they are my

mother multiplied, more — there’s always more.

What was claustrophobic for Jones — closet locked, closing in, this more which suffocates — becomes, in Mohale’s reconfiguration, totems of safety, words of comfort. In this poem, which revisits the night-room in a dream, another poet’s words function to alleviate silence. Mohale takes a quotation down from its clothespins[1] and tries it on for size, spins around, sees how it looks on their body. There is pain here: the pain of being unable to tell one’s own story all the way through. There is healing too: the promise that, if the poet is knocked back by silence, a chorus will be there to catch them.

Maroga does similar work in “griefsong.” Although uncited, the poem is punctuated with borrowed phrases: “quiet violence” from K. Sello Duiker; “the price of the ticket” from James Baldwin; “the god of small things” from Arundhati Roy. And then, of course, the refrain at the heart of the poem, “hands up don’t shoot,” spoken so many times in so many cities by so many still-mourning mouths that the chorus builds into a force of nature, a collective voice that shakes the world.

Maroga calls on this chorus of voices to help them speak through the many-layered violences of our anti-Black world. Together, they hold each other upright, so that the immense pressure of trauma endured does not bog down one poet and render them speechless. In some ways, this chorus protects the reader too. As Saidiya Hartman writes, “The chorus bears all of it for us.” The chorus fashions a radical new way of telling a story, one that can hold both the personal and historical, the event and its ripples, the silence and the scream.

Mohale has a poem structured much like “Everything Is a Deathly Flower,” with an epigraph woven into each stanza. This one, called “Diphylleia Grayi,” after the skeleton flower, cites Maroga:

Tell me where I can put you down

I’ve written the sky from midnight to dawn

and carried you all the way ‘til morning

And I am tired

[1] I borrow this image from Jacques Derrida, who likens a quotation in a text to “a garment spread out on a clothesline with clothespins.” Derrida, “Living On,” translated by James Hulbert. In Deconstruction and Criticism, edited by Harold Bloom, Paul de Man, Jacques Derrida, Geoffrey H. Hartman and J. Hillis Miller (New York: Seabury Press, 1979), page 76.

Keely Shinners is a writer based in Cape Town. Their essays have appeared in the journals James Baldwin Review & Safundi as well as the publications ArtThrob, Africanah, ASAI, Mask & Full Stop. Their debut novel, How To Build a Home for the End of the World, is forthcoming from Perennial Press.

This post may contain affiliate links.