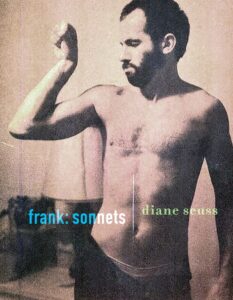

[Graywolf Press; 2021]

In the series of over one hundred sonnets (classified as such due only to their fourteen-line length) that make up frank: sonnets, Diane Seuss digs into her own life to unearth compelling personal narratives. Of course, when discussing or reviewing poetry it is normally essential to avoid conflating the speaker of a poem with the poet. But in frank: sonnets, Seuss inextricably ties herself to her poetic voice, revealing childhood memories and adult indiscretions with fierce bluntness. In an interview with Tupelo Quarterly, she explained: “My ‘I’ in frank . . . is an aspect of self, flatter than the dimensional walking-around me, but certainly a chip off the ole block.” While some poems are from loved ones’ points of view or seem removed from a singular perspective, early on in the collection it becomes clear that the driving force behind the narratives being told are the memories and experiences of their author. This choice — not an uncommon one considering the important history of confessional poetry but most definitely still a risky one — pays off in dividends.

While the stories and memories being explored in each piece are usually restricted to Seuss’s own life, their subjects have significant range. From her father’s early death, to her audacious life in New York in the 70s, to her son’s addiction, to her own relationship with her body, no moment or topic seems too embarrassing or traumatic to mention. By letting the reader in on such private interactions and memories, she creates a sense of intimacy, giving the collection a diary-like quality. This is compounded by the specific nature of her descriptions and choice of detail. She grounds her more philosophical and ambitious thoughts in concrete observations, making her sonnets feel more realized and realistic. In “[Literature is dangerous business]” she expresses an anxiety about this precise kind of poetry, in which she claims “one can find themselves not just lost but impaled on the tangible details / of someone else’s world.” But “tangible details” in frank are more buoys than stakes, keeping the reader afloat among the heavier and more private emotional subjects being tackled.

An ailing soulmate is characterized by the Joni Mitchell songs he thinks he will miss most when he dies and his posthumous plans for his car. A son materializes out of informal conversations with his mother about God and music. An entire phase of life is summed up in simple, straightforward lines: “Is it hard for you to imagine me wearing gold lipstick? I did. Is it hard / for you to imagine me stupid? I was passed like bread among strangers. / For a couple of nights, I was the new thing. Then just a thing.” Suitors pursuing her mother after her father’s death become a melange of men distinguished by cuttingly noted features, and Seuss manufactures their entire characters out of brief, distinctive identifiers. There is “an oval-headed man from across the road with dirty phone calls the night / after the funeral,” and “her friend’s husband / from Wabash, Indiana” whose “wife was strapped down getting shock treatments.” Names are mentioned in the same way names are mentioned while catching up with an old friend: dropped into conversation with the assumption that the significance will be understood. There is a faith in the reader’s ability to deduce and extrapolate, to add the pieces together and share in a rich history.

This isn’t to say that Seuss allows unmediated access to her life — sometimes the amount of personal exposure in one poem reveals how much she is not sharing in another. The figure of Kev is particularly shadowed, his ghost hovering at the ambiguous edges of some of the collection’s most enigmatic stories. Although some aspects of his personality are shown (like his violent tendencies and his impulsiveness) and he is said to be “long dead,” the poems in which he is featured intentionally withhold much of the nature of their relationship. In “[I’m watching A Face in the Crowd]” it is suggested that he may have been a cheater, and in “[Thirty-nine years ago is nothing]” as well as “[How will I leave this life, like I left my job]” it is revealed that he threatened to kill Seuss when she tried to leave him. But other than that, the dynamic is mostly kept hidden excepting some foreboding flashes in other poems. Despite seeming devastating and significant (a sense that comes with Kev’s introduction, at the end of which she calls him “he who would slaughter me”), Seuss sidesteps the reality of the relationship in a way that she does not do with most other people in her poems. While this can be frustrating after so much time spent being allowed access to incredibly intimate moments and thoughts, it gives the collection a sense of restraint that it would not have otherwise. That restraint also becomes clearer toward the end of the book, as in “[To say that I’m a witch]” when she notes: “Did I consume my life in bitter / mouthfuls? The storytelling makes it seem so but in actuality / I dragged a bit at the heels . . . .” Here, Seuss states explicitly that, although it may seem that she has allowed an unfiltered look at her life, that is not the case. There is still some editorializing, some kind of poetic distance.

Editorializing (and admitting to editorializing) is a bold choice for a confessional poet. The tangled personal and public politics of engaging in verse with intense private subjects present any number of issues for those who follow this tradition. Sometimes poets are understood to be too explicit, others as too evasive. They are expected to share but not share too much, to be artful and not too obvious. The most successful confessional poets, like Robert Lowell, Anne Sexton, and Sylvia Plath, find ways to balance adherence to the truth with artistic style. Robert Lowell is similar to Seuss in how he approaches narrative, telling stories with specific names and places, bringing the reader into his family life not by introducing relatives in a straightforward manner but by portraying them in scenes with simultaneous affection and resentment. Lowell, though, rarely seems to withhold information, and if he does he hides that in sardonic humor or a brief moment of self-effacement. Anne Sexton, like Seuss, latches onto detail in order to create a vivid personal picture, but her work is often more abstract or figurative and therefore less beholden to literal reality. Plath is alike in this, while also juxtaposing shocking realistic imagery with the fantastic or otherworldly. Seuss’s moments of poetic distance seem to be her answer to finding the balance between being honest and being ambiguous. She is taking the approaches of her predecessors and wringing from them a technique that engages with the reader sincerely but without the clumsiness of the overshare. She is confessional, but she makes sure that her reader knows she is not revealing everything there is to know, openly obscuring the exact truth in order to remain at least somewhat opaque.

There are ways in which frank: sonnets is imperfect. Sometimes the details and observations are a bit too easy or on the nose, like in the line “Eyeliner is war,” which is somewhat trite considering the amount of similar conversation that has already been had around the ways women interact with makeup. Other times the repetition of themes and images can make otherwise surprising poems feel more expected, like in “[Labels now slip off me like clothes]”, which starts with a complicated search for a father figure in a suffocatingly small town but ends with the predictably patriarchal figure of Jesus, who she has already invoked multiple times at that point in the book. It is also not a particularly subtle collection — bodily fluids, explicit conversations about sex, and moments of abrupt violence can come across as shoving its audacity in the reader’s face.

But still, all of these imperfections add to frank’s charm. These moments of met expectation or when the poems seem to intentionally call attention to themselves just add to the authenticity. What feels messy also feels real, adding honest nuance to pieces that already feel complex and genuine. Ultimately, despite (or maybe because of) its fleeting blemishes, it is a complete and absorbing assemblage of personal recollections, constructed with piercing detail and candor.

Sarina Redzinski attends the MFA program at the University of Florida while raising her beloved chihuahua, Basil.

This post may contain affiliate links.