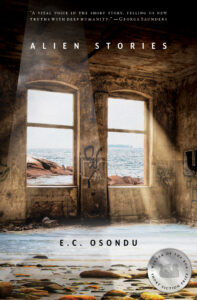

[BOA Editions; 2021]

In his new collection of short fiction, Alien Stories, E.C. Osondu plays with the dual use of the word “alien” — to mean both a person living in a country other than the one of their birth and a hypothetical lifeform from another planet — in order to highlight the confusion Americans feel when interacting with people from different cultures. Short and tightly written, each story presents a lesson that leaves the reader thinking deeply about themselves and how they relate to people from other cultures. Composed with humor and empathy for the subjects and readers, Alien Stories leverages the imaginative fun of science fiction to thoughtfully reflect on the experiences of those born outside of, but living, in America.

Before discussing Osondu’s stories, it should be acknowledged that using the same word — “alien” — to describe people from other countries/cultures and hypothetical lifeforms from other planets is problematic, as it emphasizes the otherness of the person identified with the term. The collection deemphasizes the difference between “alien’s” two usages, often barely implying the “aliens” in the story are extraterrestrial at all. Part of the brilliance in Osondu’s stories is in showing how closely a person’s imagination may link the concepts of earthborn and extraterrestrial “aliens.” It should also be noted that not all the pieces in Alien Stories work with the extraterrestrial theme; some focus on technology and others have no science fiction angle at all. Still, the title and the predominance of “aliens” in the novel draws attention to how some perceive those from other places and cultures and how their perceptions may have very little in common with what they are experiencing.

Alien Stories often avoids describing extraterrestrial bodies. Since the beginning of the modern science fiction genre around the turn of the 20th century, writers have presented extraterrestrials as a means to explore humanity and our cultures. Though speculative exobiology suggests extraterrestrials would most likely have no resemblance to human beings, in science fiction, extraterrestrials present only slight anatomical differences from earthlings. For example, the cultures of Ursula Le Guin’s Hainish universe are all variations of humanity; as are the worlds of Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series; explorers in Star Trek encounter recognizable human civilizations on undiscovered worlds. When science fiction does imagine extraterrestrial anatomy as far different from humans — as in Ted Chiang’s “Story of Your Life,” or Octavia Butler’s “Bloodchild,” for example — the cultural interactions between humans and extraterrestrials are still primary reflections of the science fiction work. For sure there are works in which extraterrestrial bodies matter significantly, such as China Mievelle’s Embassytown, but such stories are the exception more than the norm and Osondu is in good company presenting nearly human extraterrestrials.

Alien Stories begins with a piece titled “Alien Enactors.” The story features no extraterrestrials, but instead actors who perform world cultures — presumably, each performs their own — for guests at a vacation resort called “the Ranch.” The place might remind readers of Disney’s faux-multiculturalism at Epcot Center or the ride “It’s a Small World” in which celebrating a culture means reinforcing stereotypes to appease consumers’ confirmation biases about the cultures they are celebrating. “Alien Enactors” opens the collection with a clear indictment of the inauthenticity of so-called “multiculturalism” that permeates American media and education, resulting in an American inability to accept fullness and diversity of and in other cultures. The narrator, who presents African culture (note, there is no culture named, just “Africa”), is highly successful while his coworker, Ling, who enacts Chinese culture, is not. The difference between the two comes down to how much the guests relate to and enjoy stereotypes rather than how much they value learning or experiencing someone else’s authenticity.

When the narrator encounters a client who is nostalgic for his time spent in Africa, the man presents one backhanded compliment after the next. The client says he felt “more alive” in Africa, “more aware of the fact that every blessed moment could be your last” because he may get hit by a vehicle. Of course, many people are struck and killed by vehicles in the US, but the client chooses to use that example to “celebrate” the relative lack of safety he felt in an unfamiliar environment. Later, he comments that in Africa “Their sense of time is straight out of Salvador Dali’s The Persistence of Memory,” meaning people moved slowly there, in his perception.

The narrator confirms and plays along with the stereotypes, reflecting the client’s biases back to him, and is awarded with a rating of “Excellent.” Unfortunately, Ling is less effective at confirming clients’ confirmation biases about China and for her failures she is told “You are not doing enough for China” and “You are doing China a disservice.” The enactors are tokenized and their approval or disapproval by the clients represents the types of approval or disapproval immigrants and visitors face based on how closely they adhere to mainstream expectations for them and their cultures (aka, stereotypes) while in the United States.

Osondu slips in familiar lines that will (or should) embarrass US readers by aiming common microaggressions and biased behaviors at ostensible extraterrestrials. If something sounds ridiculous to say to someone from another planet, how ridiculous is it then to say it to someone from another country? For instance, the third story in the collection, “How to Raise an Alien Baby,” begins with the lines, “Rules are rules. They exist for a reason. They are meant to be obeyed.” In the story, these words introduce the expectations for fostering an alien child, but they echo the types of a-critical, vapid things many Americans say about immigration. They remind readers of the so-simple-it’s-fragile thinking that believes bifurcating North America with a wall will keep people within national boundaries, like the way a fence supposedly keeps neighbors out of one another’s yards. Hyper-simple thinking about complex issues results in transparent hypocrisy. For example, one of the rules for hosting an alien baby is “no television antennas” — all must be removed for security fears. Security fears represent a significant propagandist influence tool targeted at rural Americans, in particular older, white Americans, and the narrator’s twisted rationale is darkly humorous in its familiarity:

Let’s say we plan to attack their planet tomorrow, to seize it and make it our own, to force them to come harvest our potatoes, our almonds and tomatoes, our oranges and grapes, and so on and so forth. As you well know, in warfare, surprise attack is the mother of victory. So here we are, planning to strike with the utmost surprise, and your house guest — your innocent alien baby gets a hold of this information and decides to give his people a heads up. What do you think they’d do if they get this actionable piece of information? Of course, they would strike our planet. And you bet they wouldn’t show mercy. Before you know it, they’ve annexed our home — our dear mother Earth — and taken us to their red, dusty planet and forced us to break rocks all day while we sing “By the Rivers of Babylon.”

Within this short exchange in the aggressor’s perspective, we see the aggressors switch roles with the victims — a familiar narrative woven by people who would hate to have others do to them as they would do to others. The story indicates an imperialist ethos that haunts American culture to this day and presents several other instances of cultural hypocrisy, replacing “country” or “culture” with “planet” or “aliens.”

In “Visitors,” an extraterrestrial family moves to a small town and the narrator’s wife invites them to dinner, despite her husband’s (the narrator’s) trepidations. Before meeting the family, the narrator suggests, “They should have moved to a big city. It is quite easy to hide in a big city. Not that I think they have any reason to hide, but you never know. There are not many of us here and it is quite easy to stick out.” Later, the narrator says the visit reminds him of when his wife hosted a family from Africa, which also made him uncomfortable seeing as his only knowledge of Africa came from the 1980’s film “The Gods Must Be Crazy.” Though the narrator finds common ground with the alien family over football and parenthood, it’s clear that the author knows the intricacies of the I-fear-that-which-I-do-not-know strand of bigotry common in the United States. The narrator’s acceptance of the visitors occurs because their presence dispels his anxieties about their difference from him, but really it is a form of conformity on the part of the visitors – they conform to the narrator’s ideas of how people should think or behave. Things like sports and raising children are predictable commonalities that do more to show the stupidity of the narrator’s original biases than anything about the “aliens” themselves.

“Feast,” the short tale following “Visitors,” exposes a different strain of ideological violence — the ways cultures use ritual and communal practices to nestle violence and hate within group unity and togetherness. On Alien Feast Day — a day of ritual and celebration — one alien is hanged as a sacrifice. The story does not tell the history of the day or what the people expect to accomplish through the ritual, but hanging invokes lynching, itself a practice that became the center of celebration and ritual in the century following the US Civil War in which African Americans were hanged in community-sanctioned, extrajudicial murders. The celebrations that followed the murders involved huge crowds photographing themselves alongside the murder victims — a community action that allowed the murderers to be absolved through social ritual. Many lynchings went unpunished. The murderers were those representing justice, either formally like police or informally, as members of groups like the Ku Klux Klan.

In “Feast,” the hanging is accomplished with few words — “The rope was fastened around the alien’s neck. The lever was pulled. The neck snapped. The alien was dead.” Most of the story focuses on the diversionary tactics the community uses to recast a murder as a ritualistic sacrifice, as spectacle: the children wonder what food the alien will order for their last meal, what color the alien will be, and whether or not the alien would be hooded. The reader learns at the time of the execution that the alien’s face was not covered at their own request and “according to the Elders this idea of deciding whether to have their face covered or not was yet another proof of how much choice the alien had in the matter.” Elevating an insignificant detail and infusing it with meaning is a staple of American racism, the kind of thinking that attempts to excuse slavery on the alleged grounds that some of those enslaved developed affectionate relationships with slaveholders. Violence done to African Americans and other people of color in the US is hedged in flimsy justifications. Osondu’s fable illustrates this reality, making it accessible through fantasy.

The story following “Feast,” which is called “Sacrifice,” imagines a town forced to sacrifice one youth a year to an alien spacecraft that arrives to receive the offering. Poignantly, the narrator, who is a member of the community forced to surrender a young man, immediately identifies the townspeople’s acquiescence with the ritual as only due to an unavoidable threat of violence. He says, “All we had were our machetes for farming, our single barrel guns for hunting, and our fishing nets and hooks. There was no way we were going to be able to fight them and their spaceships that glided through the air. They could wipe us out at the press of a button.”

Military technological superiority is accepted as an immovable facet of reality and seemingly advanced technology overwhelms victims with fear. Historically, military technological superiority underwrote early modern European colonialism in Africa and in North and South America. This trend continues today. When we consider that the US Department of Defense received 705.4 billion dollars in 2020, more than the next ten countries combined, we see how the capability to inflict harm remains a force unconstrained by dialogue. When the aliens in “Sacrifice” arrive in a spaceship, a show of power rural farmers cannot hope to match, readers understand the people’s feelings of helplessness as a metaphor for US empire building abroad.

“Sacrifice” follows Makodi, a relatively cantankerous woman who refuses to give up her son, Obiajulu, when he is chosen as the sacrifice. She struggled to have a child and, as her only child, she is overprotective of Obiajulu, often intruding in his life in ways that draw the reader back to their own caretakers’. However, the way Osondu lets readers roll their eyes at Makodi for the first half of the story, only to turn her into an exemplary hero as the plot progresses, was a surprising reward. When it is time for Obaijulu to ascend the stairs into the spaceship, Makodi defies the whole village and decades of tradition because of her love for her son — and the aliens allow it. The idea that an individual can break from expected behavior and be the catalyst for change is an encouraging message. If only the military industrial complex on Earth was as ethical — or at least had the potential to be — and mysterious as the alien visitors in “Sacrifice.”

Later, in “Traveler,” a narrator finds himself in conversation with a fellow train rider intent on telling an immigrant all his presumably right-minded ideas about immigrants. The story is a kind reminder to readers not to do that. At one point, the narrator thinks to himself, “I wondered if he knew that cultures that showed hospitality to strangers tended to be conquered and overrun by those same strangers with time.” The statement captures both the reality of colonialism and a persistent fear that nativists hold about immigration.

As previously noted, some stories in this collection abandon science fiction entirely, such as in “Debriefing” — a story divided into sections, each of which offers a brief snippet of advice to people immigrating to the US from Nigeria from an immigrant who has been living in the US for some time. The first section reads:

Do not buy a car. Do not drive. Ignore advice to obtain an international driver’s license before your arrival. American cops do not know what an international driving license is or for the most part they pretend not to know. What they don’t know makes them angry. You do not want to face an angry American cop. Driving is a slippery slope. Driving is trouble. Driving is tickets. Driving is a cop asking you for your license and registration. Before you know it, you are standing before an elderly grim immigration judge.

The contrast between appearance (a license allows you to drive) and reality (racism prohibits you from driving) comes through in many of the warnings in “Debriefing.” Would-be immigrants are warned to dress properly and take accent reduction classes. They should take Amtrak and avoid people named “Chuck.” The many pitfalls of American society, as they may be experienced by immigrants, and as written about in the book, are neither obvious, logical, or fair; and many center around catering to, and therefore upholding, racism and bias.

Like “Debriefing,” another story, “Focus Group”, is constructed out of short sections. Returning to the alien theme, each section features one focus group participant’s feelings about aliens. Again, the aliens in this story are ostensibly of the E.T. variety, and again, the comments made are reflective of all things people really say about immigrants and people from differing cultures. For example, if an alien is green, a character asks, “Why can’t they just be white like everyone else?” (as if everyone else is white…). The general responses to the aliens range from physical revulsion to envy, from skepticism to comparison, but each one simmers with a level of fear. There is one section featured in “Focus Group” that focuses entirely on food and reinforces an idea present throughout Alien Stories: that immigrants are often seen, and therefore offered a form of socially acceptable visibility, through the lens of the local restaurant, selling their home cuisine to American customers, however authentic or inauthentic it may be. But there is a point to Osondu’s focus on this reductivism that simplifies a culture to its cuisine, as it helps remind readers they don’t have to form a connection with their own point of greatest familiarity as the starting point. People can find deeper, less superficial points of connection than cuisines and international news, and looking for deeper connections helps prevent people from reducing immigrants to a preordained slot in the community — too often, a local restaurant.

As perhaps this review makes clear, Alien Stories gives readers much to think about and it’s a book that certainly invites conversation. Readers of different backgrounds may experience the book in different ways. An immigrant may nod along knowingly. Readers of color may feel differently than white readers, though, at some points, Osondu makes clear that Americans of all identities may “alienate” immigrants; there are moments where he is clearly writing to Americans of color. Certainly, though, Alien Stories gives white readers an opportunity to understand more about what immigrants, and particularly immigrants of color, experience and reflect on the behaviours of support or “alienation”. The collection would certainly prompt productive discussion in a college classroom. Before becoming an author, E.C. Osondu worked in marketing. This is notable because Alien Stories feels very aware of itself and of how to make meaningful ideas connect with a broad audience: the stories are accessible, but thought-provoking, with clarity and concision. In each brief piece, readers encounter tightly focused ideas that expand exponentially the more one thinks about the stories. It may even make you rethink using the word “alien.”

Eric Aldrich’s writing has recently appeared in Terrain.org, Euphony, Hobart, Manifest West, and Weber: The Contemporary West. His novella, “Please Listen Carefully as Our Options Have Changed” is available from Running Wild Press.

This post may contain affiliate links.