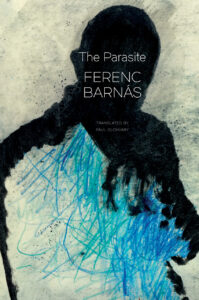

[Seagull Books; 2021]

Tr. from the Hungarian by Paul Olchváry

About 50 pages into Ferenc Barnás’s The Parasite I settled myself down for a ride that I thought would be like one of Thomas Bernhard’s, but darker, and more oblique, since Barnás was a Hungarian. Centraler the Europe, higher the uncanny stakes. Here was a story of a boy who loved being in hospitals and who made up maladies to visit as often as he could, to stay as long as possible. This was an excellent start: a character who doesn’t feel safe in the outside world and who can read all kinds of social ills in the physical ones he encounters in the hospital. Our protagonist soon runs out of physical symptoms and so takes recourse to psychiatric illnesses, harder to diagnose and to cure. This is the ward where he is introduced to the ways of the flesh, by a nurse, and then his existence is completely consumed by his relations with the opposite sex. From that point on, the contract I thought we had with the narrator, of being offered a novel where the hospital would be a metaphor for the ills in Hungarian society, is abrogated.

When his formative years in hospitals are over, our protagonist is somehow launched into the real world of adults, but all we get to learn about him is the string of girlfriends he has, culminating in L, the one that has led him to write this account of his life. We do not really know what he does for a living, or where his attraction lies for these women. His lack of job prospects, and the toll the needless treatments he has had since childhood must have taken on his body seem to detract nothing for these nymphs. Like in the novels of Haruki Murakami and Michel Houellebecq, the women appear out of nowhere, are happy to spend time with him, and then disappear to where they came from to make room for the next stage of his self-fulfilment, if one can call it that.

In order that we do not think that he has it too easy, Barnás gives several idiosyncrasies to these aethereal women. They are not ideal girlfriend material, you know. Our parasite latches on to them and they have several adventures together until the experiment proves too much for the one or the other. Here, of course, is the spectre of Huysmans and his Jean des Esseintes, the “experiencer” who stretched his senses to the limit, including when seeking sexual pleasure. This channelling of the French author ties Barnás even more closely to Houellebecq. Barnás proves the more ardent disciple of Huysmans, however, and gives us page after page of what he gets up to in bed with the girlfriends, leaving nothing to your imagination.

In short, if you like novels that objectify women, you’re in the right place. Our hero leers at a woman, and before she even goes to bed with him, as she must, he has exhausted her through his gaze: “I now knew more about this young woman than one should, I thought. What would I talk to her about, if she opened up so much even without words?” Is there really any point in pursuing her at this stage? Apparently, there is. Although by now she is already a husk in his eyes, he walks up to her to introduce himself. On cue, the pop music stops and “spirited Arab tunes” start to play, in case you didn’t quite see where this was going, what the tenor of their sexual encounter will be.

Intimacies between random strangers can be interesting to a certain degree — Louise Doughty’s Apple Tree Yard comes to mind — when we are told what it costs the pair, how it becomes an interruption to their old routine. But there is no routine or convention against which the narrator’s “trespasses” happen, and so all manner of excitement is choked out of them. That may be the point Barnás is making, you may well claim. If that is the case, he would have been wise to share with us maybe 10 pages of this tedium and not 130.

After a couple of such encounters, the narrator meets his equal in the last girlfriend, who is, we are given to understand, as “damaged” as he is. The relationship is going to be intense, and there will be many submission and abandonment games to be played. Here is also a woman he apparently cannot read at first sight, can’t exhaust by simply gazing at her. Finding himself in this foreign territory, he decides to take the reins the only way he knows how. At the end of Part I he informs us that in order to understand her — speaking with your partner to that end is for wimps! — he will be making up her backstory.

He imagines all kinds of debauchery she must have got up to that prepared her for the ultimate relationship, with himself. Narrating L’s past, he inhabits both her mind and the minds of the hypothetical men she’s been with — calling to mind that nightmarish contraption used to horrifying effect in the film Strange Days. He is now the master of her experience, and is able to be with her, not just through his own body, but through this imagined man, who, just like himself, turns out to be a gentleman:

True, projecting his sensuality into the other’s body was something he handled with utter care, for otherwise the method could have degenerated into self-gratification, which he would have been loath to let happen.

Even when the reader may want to distance this hypothetical lover from the protagonist, he keeps suggesting that they are very much alike. After we get the whole sordid story, we go back to the protagonist’s reality, where he tells us about the process of writing L’s imagined story:

I found it impossible to cease wondering, even as I posed L. some commonplace query, such as what she’d done that day: What had happened to her in my story . . . If she reported having felt sad that morning, right away I suspected either that this sorrow had descended upon her right out of one of the chapters of my fictional story, or vice versa: it had been precisely on account of her condition that morning that I’d been able to capture this feeling in the sentences I’d been about to write.

He is assured of the potency and centrality of his narrative powers. His story makes things come to pass and/or his story is a sentient being that captures whatever is in the air. For all we know, he has written the Great Hungarian Novel. In him we have the embodiment of a male and privileged connection to reality and narrative. Somewhere in his story he also announces what L thinks about women: “In recent days L had in fact pondered this at length before arriving high-handedly at the simplistic conclusion that every woman is a whore.” Just to give you a sense of how tedious her debauchery is, here’s a passage of what L gets up to: “Next, she slid her grateful hands onto her breasts, her belly and her thighs, and finally onto her loins. L now felt the same sort of tenderness and love towards her own body that she had on that night on seeing the coroner’s hands.” Does this interlude in the novel, and The Parasite itself, respond to some need for navel-gazing in contemporary Hungarian society? There is no sense of place, or a society at large, in the novel, and so if this senseless repetition of the sexual act is indeed a metaphor for current Hungarian concerns, the reader will have to do their own research to find the tenuous link.

I, with all the metatextual smoke and mirrors Barnás tries to provide to excuse it, am not keen to read this sort of writing pages on end. It would be just about bearable, if, like in Nabokov’s novels, there were enough pointers to tell us that the narrator is deranged. I do not know what we’re supposed to do with the straight-faced narrator’s fallacies and fetishes. Sympathize? See them as a pathology and pity him? Neither seem very palatable to me. Towards the end, his final plea to the reader is that he himself is a work of fiction. Shall we, then, direct our frustration directly to Barnás?

Undoubtedly, I was the author of my work, but in no case could it follow that I was one and the same with it. Sometimes I believed that the pathological thinking in the sentences didn’t even originate in me. At such times I became suspicious. Had it really been I who thought that villainy, or quite to the contrary, was it imagining me in such lowly terms?

Is this metatextual sophistry enough to let him off the hook? Reader, it is your choice.

Nagihan Haliloğlu is a lecturer and reviewer who lives in Istanbul, where she teaches graduate courses on literature and writes reviews for the Turkish monthly magazine Lacivert. She also occasionally contributes English pieces to Daily Sabah.

This post may contain affiliate links.