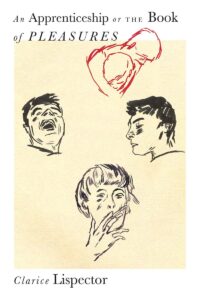

[New Directions; 2021]

Tr. from the Portuguese by Stefan Tobler

Cockroaches. Class. The caps of waves. Fruits. Where Clarice Lispector’s eye roves in her fiction is beguiling, to say the least. The Brazilian (post)modernist wrote sticky, introspective fiction. Reading her novels feels akin to sucking in one slurp the entirety of a cold drink through a straw. Your teeth hurt, but your head is clear, satisfied.

It is difficult and inadequate to say her novels are “about” specific plots. More feasible, perhaps, are endeavors to track her pursuits. One of these is the relationship between the self and pleasure. The other could be said to be apprenticeship — or pedagogy. Another way to think about this is: how to make oneself understand one’s need to be human?

Her debut novel, Near to the Wild Heart (1943), follows a young, creatively agitated woman named Joana. In one of the episodes that makes up the novel, Joana’s teacher, “who still didn’t know she was a viper,” we are told, instructs her on the value of human life as being in relation to pleasure. “All yearning is pursuit of pleasure. All remorse, pity, benevolence, is fear of it. All despair and seeking alternative routes are dissatisfaction. There, you have it in a nutshell, if you wish,” he says. “Do you understand?”

This question resurfaces in an adept new translation of her 1969 novel An Apprenticeship or the Book of Pleasures. It is, in part, as has often been described, a love story: between Lóri, a school teacher, and Ulisses — a name that becomes difficult to look past — a philosophy professor. The novel sets up a Socratic dialogue of sorts between the two. While Ulisses cannot help but come across as a gently patronizing man who, despite himself, offers moments of tender insight, Lóri is whom the novel asks us to be close to, in narration and sentiment. Each is an apprentice to the other, and Lóri, we see, is a hungry student of life. If Ulisses insists on waiting for Lóri — “waiting perhaps for you to give yourself advice” — Lóri is happy to make him wait. The waiting, of course, is living. The enchantment of the story is irretrievable, like the expectation of glamor.

The deep pleasure of living requires seeking it amidst daily heartbreaks. Lóri and Ulisses speak, somewhat, of God, and of other forms of metaphysical reckonings, seeing living well as itself a spiritual undertaking: “Not pray the Lord’s Prayer, but ask something of yourself, ask the maximum of yourself?” suggests Ulisses.

And so Lóri does. She embroiders, she takes herself out to the movies, she “lets the phone ring a little more, not wanting to look too eager.” She goes to the beach at six in the morning and has a near-sacred experience with the water. She enjoys saying the word “mesophyll,” which Ulisses tells her is “the fleshy part of the leaf.” She inhales night jessamine, unready for its strength. She bites into a ripe pear at the market and becomes aware that “only someone who has eaten a succulent pear could understand her.” Lóri’s interiority becomes a medium to experience the sublime. In a sensual moment where she considers if she wants to take Ulisses’s hand, Lóri enjoys the wanting more than the possibility of holding his hand:

She knew the world of people who anxiously hunt down pleasures and don’t know how to wait for them to arrive on their own. And it was so tragic: you only had to look around a nightclub, in the half light: it was the search for pleasure that doesn’t come by itself and of itself.

The shadow such Epicureanism casts is long and sweet: watching Lóri live with such vitality, mirrored in the style of Lispector’s prose, is intoxicating. Lóri pushes against her fear of — and comfort with the idea of — death. As readers, we catch on, fellow apprentices in the art of pursuing daily pleasures. Taking, thumbing through, and zooming into images documenting these. A column of golden hour sunlight streaming into a carpeted room. Hands clutching a nosegay of sweetpeas. Fine dust falling from a bow as it pulls over the strings of a violin. Soft, afternoon rain. A car speeding across a bridge at night. Pulped tomato spilling on to the floor, clotting.

The joys are “flooded bit by bit,” for Lóri. Her autodidact attempts to put herself together for herself, to learn how to be in the world, are incremental. “Anyone who wasn’t strong enough to take pleasure should cover every nerve with a protective coating, with a coating of death in order to tolerate the mightiness of life,” she thinks. The novel hurtles towards the question of whether Ulisses and Lóri will ever get together. We readers don’t have to agree to ask it, or care for it being answered. The novel that begins with a comma and ends with a colon offers much more — Lispector’s fiction pushes us to become apprentices of language itself, to find pleasure in the cadences of subjectivity, and to seek out how our articulations of desire and pain weave our reality.

Sharanya teaches and writes in west London.

This post may contain affiliate links.