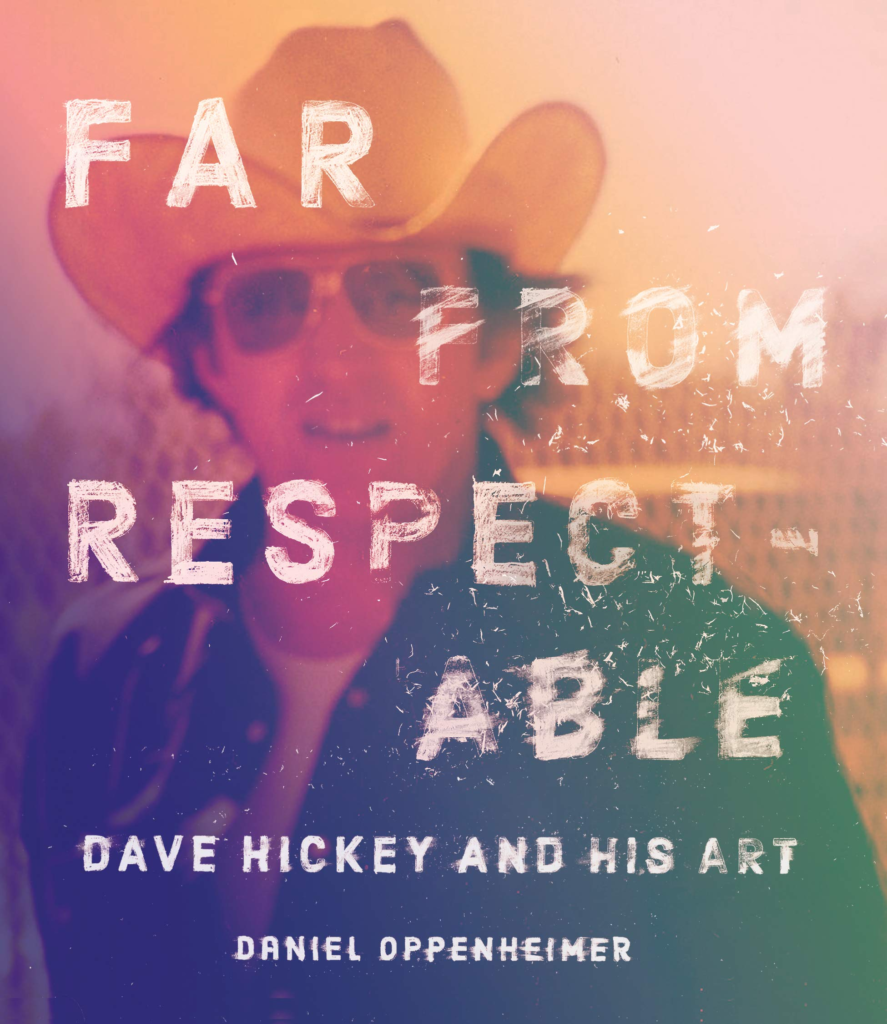

A study of idiosyncratic gonzo art critic and essayist Dave Hickey was not on most of our 2021 bingo cards, and yet we have Far From Respectable: Dave Hickey and His Art, Daniel Oppenheimer’s engaging study of the idiosyncratic critic coming out this month from University of Texas Press. It turns out revisiting the rabble-rousing critic and 2001 MacArthur “Genius Award” recipient qualifies as comfort food, especially for those who treasure his 1997 collection Air Guitar: Essays in Art and Democracy. Daniel Oppenheimer, author of 2016’s Exit Right: The People Who Left the Left and Reshaped the American Century, combines gumshoe reporting, interviews with figures in Hickey’s life, as well as plenty of fan service nuggets, and the result is a short book that both humanizes Hickey and burnishes the mystique.

Daniel and I talked one afternoon to discuss Far From Respectable, Yoko Ono, the 90s art world, Hickey’s Pagan America manuscript and his shambolic lives as a blissed-out Austin and New York gallerist and Nashville songwriter.

Daniel Nester: First things first. Why a book about Dave Hickey and why now? Dave Hickey is getting old, right? He’s 80?

Daniel Oppenheimer: He’s 82. He’s 80 if you go by Wikipedia. He’s always been a little fuzzy on dates. I found his birth records. There is the census with his birth record in 1938. I also found his father’s death certificate. He always told people his father killed himself when he was 11 or 12. Actually, it was when he was 16. He was also telling people we went to college when he was 15 or 16, but he actually went to college at the normal time, when he was like 17 or 18.

Is that a case of self-mythology going on there?

I don’t think it’s deliberate mythmaking. I genuinely think there’s probably some narrative of himself that probably serves some psychological need, but it wasn’t like he was saying look at what a genius I was.

The why of the writing of the book goes is easier to answer, in a sense. I got Air Guitar from my brother when I was 20, and I thought this is amazing.

Just the right age.

Totally. And so I became a Hickeyphile. I went back and read Invisible Dragon back when it was very hard to get. Maybe the more interesting answer to the “why now” question is I think it’s an interesting time to write about Hickey. He became a name and he made his name in conflict with, or in critique of, for lack of a better word, political correctness in the art world in the 90s. And then that kind of went away, but it turns out, it didn’t go away. He’s not in a place now to critique it in the same way with the same kind of energy to be in the mix.

There were these books edited by Julia Friedman, Dust Bunnies and Wasted Words, where she collected all his Facebook posts. They sort of address our current culture in an aphoristic way.

You’d have to have an immense amount of rhetorical nimbleness to navigate today’s landscape. I can think of people right now who are doing it, but they’re people more in the prime of their intellectual lives. I don’t think he could kind of walk that tightrope. I don’t want the book to be read as just like an anti-PC woke polemic or something, but if you’re asking if he’s relevant right now, for me, the answer is yes.

We’re going through the same thing now. In the ’90s, it was mostly contained within academia and the art world, and now it’s sort of everywhere. And the desire to subordinate art to various political and moralistic ends is everywhere. I don’t know how people will read the book, but from inside my head, I do think people need to read Dave. Artists need to read Dave. I need to tell all these other people who are telling me what to do with my art to go fuck themselves and figure out, you know, what I need to do with my art. Maybe it’s political, maybe it’s totally abstract, but I need to figure out what my vision of the world is and how I manifest that in my art, my literature, my painting, my music, and basically say go fuck yourself to all the people who say you need to serve the cause.

Along those lines, I found myself sinking my teeth into the section in your book where you discuss the exchanges of words with curator Amelia Jones that center on a show Jones curated in 1996 at the Armand Hammer Museum at UCLA, Sexual Politics: Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party in Feminist Art History, and some of the negative reviews it got at the time.

My takeaway is that I would probably fall on the Jones side of the debate, especially considering the times we live in, but as far as the writing goes, it’s an unfair battle.

You’re right. It is unfair. It’s funny. The one person, I think literally the one person I’m worried about reading the book, is Amelia Jones. She was so nice to me. She was also very open with me. She said that experience was traumatic for her, and I can see how it was, especially since this all occurred early in her career. Christopher Knight was rabid, savage in his review in the L.A. Times. So in a sense I’m reenacting this for her in this book. And although the focus is on Hickey, I did my best to be fair to her and not take cheap shots.

I think the episode puts into perspective the Cult of Hickey that was emerging even then.

She did sort of come for him in the essay.

And Jones is now an accomplished professor of art and dean at USC. I went and looked up Jones’ essay because I had to remind myself that it wasn’t even in reaction to a specific piece Hickey wrote.

He was friends with Christopher Knight, and there was also the one that Hickey’s wife, Libby Lumpkin, published in Art Issues. Amelia Johnson also published pieces for them, too. So I think what she felt was this betrayal.

It makes me think that Hickey perhaps looks at the world of art making and art criticism as sort of beside the point. It’s not his subject, not really. He’s almost seeing his world on the page as a more rigorous one.

I’ve thought about that. I think he’s great, but I also think he was swimming in a very small pond. You think the American art world, it’s a huge world, right? It’s not a huge world. Not back then, at least. It’s a small number of people. Particularly critics. It’s a small community. Most of them are academics. They’re not especially good writers.

Fast-forward to now, and the art world has suddenly become, you know, this blockchained gonzo bonanza. When Hickey first started out in this little gallery in Austin, there weren’t tech billionaires buying Jackson Pollocks.

It was certainly a world of wealthy people and institutions that bought art, but it was not on steroids like it is now. The 80s is when that really started to get supercharged. One of the things that people said about Dave, and on this that I think is fair, is that a lot of what he writes about is the role that the gallery and the buyers play in this. From his perspective, it’s the positive role that galleries and buyers play in commerce, the production and consumption of art. He is a capitalist or somebody who’s in favor of free enterprise. He admits this at certain points when it was a much smaller and local context, when art was not so much an investment endeavor. It just wasn’t supercharged and celebrity-focused in that way.

He was trying to defend and protect spaces that felt healthy to him, like when he had his own gallery. He felt there was a proper relationship between artists and galleries and institutions. And then he felt it was really getting calcified by the growth of institutions. He was attacking the growth of the institutions and the funders, the nonprofits and museums, saying this is impinging on this delicate ecosystem.

But at this point, you know, the other side of that doesn’t really exist, either. He may just sort of throw up his hands.

He made his bones at his gallery in Austin with the very literary name of A Clean, Well-Lighted Place. I was surprised that it was only a two- or three-year period.

I have been working on a piece for Texas Monthly about the gallery. You’re right, it was a finite amount of time. The gallery opened around 1967. I don’t have a hard date. I think sometime in late ’67 he opened the gallery, and had the first show in early ’68. He was done by early ’71. It’s really three or four years.

From the start, part of him was thinking, I’m going to get to New York, but part of him was also thinking, the more important part is my job is to get this stuff noticed in New York. From the very beginning of the gallery, he had a deliberate set of strategies to get his artists and his gallery noticed in New York. He was trying to get them into the Whitney Biennial. He went to New York, networked. He took out ads in Art Forum and Art in America for his shows in Austin.

Which back then was not a thing. Nowadays it is a normal thing to see an ad for shows, in, like, Milwaukee galleries, but not then.

Right. He was very savvy. It’s funny. In most of his life, he hasn’t been savvy or strategic at all, but during these periods, he was very savvy. Hickey wanted the artists in his gallery to be taken seriously at the highest levels of American art world, and he really did it.

Who were the people he was promoting? Terry Allen was doing music back then, so it wasn’t him, not yet at least, right?

He did show Terry Allen back then. Stephen Mueller, who went on to be pretty big. George Green is another. Bob Wade, who’s down in Dallas, who ended up doing pretty well. Luis Jiménez, who was originally from El Paso, a sculptor who died in an accident. Jim Roche, who’s now in Florida, who was in the Whitney Biennial once or twice through Dave’s intercession.

And then Hickey moved to New York. Was it to make his name as a writer?

He was already writing some pieces for Art in America. Reese Palley was looking for somebody and he got the job because of his work as a gallerist. Dave was also doing some writing.

But he didn’t last long at Palley’s SoHo gallery. He really left in 1972 because he didn’t want to put up a solo show for Yoko Ono? You would think it would be a good career decision.

I can tell you what he told me. Dave was a pretty hip art guy at that time. And Reese Palley was a guy who sold tchotchkes on the Atlantic City boardwalk. I think Hickey was bored.

Dave has a long history of stupid decisions. He’s not strategic at all. I think he was also probably doing a lot of drugs. He was living it up in New York in the 70s, blowing up his marriage. He didn’t like working. Maybe the Ono thing was the last straw. Maybe that’s, if not total bullshit, it’s 50% bullshit.

I want to try to find a common thread with Far from Respectable and your first book, Exit Right: The People Who Left the Left and Reshaped the American Century. I would imagine, for example, Christopher Hitchens and Hickey would get along like gangbusters.

They might, for a while at least. Unlike Hitchens, David really is an artist. At the end of the day, Dave doesn’t care about politics. He cares about art and books and music a lot more. He’s not trying to prove a point, and this wrongfoots people, because in some of his best known stuff he is not making some argument. He takes an idea, he explores it where it goes. There’s energy, A lot of times there is a political context. But what he is doing is approaching his subjects as an essayist, as an artist.

There is a Montaigne quote I like to say to my students: “Let attention be paid not to the matter, but to the shape I give it.” When I read Hickey’s essays, I often forget or lose sight of his subjects. There’s one in Air Guitar, “The Heresy of Zone Defense,” where I forget we are talking about basketball about four paragraphs in.

It’s a very fruitful way to think about the world. You hold it in your hand. Insights don’t have to be true, to be good or useful.

Hickey presents a way to make your way through the world as a thinker. I put him on the same shelf as Susan Sontag or Lester Bangs.

He’s so orthogonal—I think that’s the right word—to the way that people are typically framing these things, right? As a teacher, or for a student, there’s something so wonderful about that. We all fall into these binary ways of thinking. Dave might see an argument that says capitalists are bad, and people who believe in the autonomy of our common good or something like that, right? And Dave writes, I’m not going to go in either of those directions. I’m not going to fall into either camp. I’m going to tell this story instead. The conclusion is you’re actually thinking for your fucking self. Even if you don’t agree with him. Maybe that’s the goal.

There is a Google Books entry for Hickey’s nixed project, Pagan America, which would have been Hickey’s magnum opus, I’d imagine, something akin to Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project. Is there a manuscript in a box somewhere?

It’s very hard with Dave to know for sure. I am 99.9% sure there is not an undiscovered manuscript of Pagan America. A bunch of the writing ended up in his columns. Some are in Pirates and Farmers. I think there was a period of time in the 2000s and early 2010s when he just lost the thread. The circumstances have to be just right for Dave to really get it together to do his best work. And I think, in my opinion, after he left UNLV, it started to fall apart.

What, exactly, fell apart at University of Nevada, Las Vegas? He makes it sound like he was cast out of the academic Eden, but I wonder if it’s any different than other academics who just retire.

This will be necessarily vague. To really answer that question, you’d have to interview a bunch of his colleagues. From what I know from him, he wasn’t liked, and his wife wasn’t, either. I think he did have friends and colleagues there who respected him, and administrators liked him after he really became hot shit. One thing he said to me was, “I always kind of did my own thing and didn’t play to departmental politics.” Maybe he didn’t serve on committees, or he didn’t go to the cocktail parties or something like that. He said that he annoyed his colleagues, but as long as he wasn’t anybody in particular, it didn’t matter. And then, after he started becoming Dave Hickey, after the MacArthur Award, things changed.

He had a full career there. He was hired there in the late 80s. He got his gold watch. What I’m getting around to is it sort of serves some Hickey Mystique to say he was run out of town.

When things were good for him at UNLV they were really good. I think it was sad for both of them to leave. It wasn’t an opportunistic time to go. They didn’t have a choice in terms of money and benefits and things like that. It’s possible also, maybe he was running out of steam and wasn’t that interested in teaching anymore.

In YouTube videos, he’s always got his Starbucks cup near him. What’s Hickey’s usual order at Starbucks?

Not sure. I think it’s some frothy, sweet confection or something. I will tell you that when I went to his house in Santa Fe, and he opened the fridge, basically, there were like, eight of them. It was, like, filled with them.

You mentioned how the Hickey household has MSNBC on all the time. You interviewed him during the Trump years. Did he see this as some warped version of his pagan America?

Obviously, in a sense, Trump is a pagan. But it’s not the kind of pagan Dave was talking about. Politically, Dave’s just like a standard-issue Liberal Democrat. I think he said to me once he recognized Trump because he knew Steve Wynn pretty well, the Vegas casino magnate.

Do you know who he supported in the democratic field, like when it was like 27 people?

I am pretty sure he was an Elizabeth Warren person.

I thought maybe Dave Hickey would have gone with someone out of left field, like Tulsi Gabbard.

It was just a visceral thing. There was a glint in Warren’s eye that he liked. Maybe she seemed familiar to him because she’s from Oklahoma. It wasn’t because of her policy positions.

When he’s being written about, you know, people talk about, Oh, he’s got a Goodyear jacket on and a baseball cap. You can make it sound like it’s like he’s like a rebel or something. What I found out by visiting him is that in terms of his, what he eats and how he dresses, he is just a lower middle class guy from Fort Worth. You forget that.

When in fact, he has an unpublished thesis on the syntactical patterns of Ernest Hemingway.

It can also make it sound more deliberate than like, he dresses like that, because that’s how he dresses. He eats junk food and he drinks sweet Starbucks coffees.

You interviewed his younger sister, Sarah, to ask about his childhood.

She was great. I didn’t write about this, but his sister was an incredibly successful Quarter Horse breeder. His sister was another part of this interesting family. His younger brother is an alcoholic and kind of a disaster. His sister was an alcoholic, was married, had kids, divorced, and ended up, I don’t know if she defined herself as gay, but ended up being with a woman for the last many years. And she was a big shot in the horse breeding world.

Hickey’s amazing life as a small-time songwriter in the outlaw country scene is touched upon as well, from his songs for Bobby Bare to Marshall Chapman, his ex-girlfriend and country singer. That fax that Chapman sent to Hickey after he won the MacArthur Genius Award in October 2001 is amazing. You reproduce it in the book: it’s an itemized invoice that totals $430,894.00 with entries for “therapy (mine)” for $11,520 and “sex (just to shut him up!)” for $219,000.

That fax is amazing. Marshall and Dave are still friends. I interviewed all his exes. There’s another ex, Susan, who lived with him in Fort Worth in the 80s for many years. And his first wife, Mary Jane, was very nice. They touch base every once in a while. They are all just kind of like, Dave was impossible. He’s a man-baby. But I love him. For somebody who has so many hard feelings towards him, people really have a soft spot for him. Which is not to say he hasn’t left people with a bad taste in their mouth. They might say Dave’s impossible or can be a total asshole. I think there are brief interactions when he’s in public when he can lean into being an asshole in certain ways, maybe to deal with social anxiety.

There was a woman I talked to, an artist, who told me a story. She had written a piece about him that was somewhat critical. She said she was an art student when he came to do studio visits. And he came to her studio and really liked her stuff and said a bunch of nice things. She was feeling great. Then, as he’s walking out of the room, he just makes this offhandedly sexist comment—it was about her process with resins or something. And he says something like, leave it to a woman to make to make it that complicated.

Sheesh. I could totally see Dave Hickey saying that. Did he read your first book?

Oh, God no, of course not. Dave’s never going to read this book, which is actually about him. It’s funny—one time, he asked me, are you any good? As a writer or something, he meant. And I said, Well, I’m not as good as you on your best day. But I’m better than you on your worst day.

Nice.

I think that’s true. I’m not as good as him on his best day. But I think this book is considerably better than a lot of mediocre crap that he’s read.

You know, towards the end of your book, I have to say, I realized that a lot of the people I find myself drawn to as a writer and as a reader are older men, about my father’s age, who just keep plugging away. You don’t seem to have the same father issues as I do—mine was a brilliant guy, a truck driver who had all this unfulfilled promise. It was unexpected to read your thoughts on dealing with this subject you admire and seeking some fatherly approval.

That’s an interesting question. Who doesn’t have father or mother issues? I think you can look at Exit Right as a working through of stuff with my father, a lefty who’s an avatar of noble commitment to the cause. On my mother’s side, her grandparents were communists, but in our household, it was my father’s left-wing politics that were the North Star. Exit Right was a way to think through some of this. It was a way of killing my father, just to put it bluntly, and to figure out what my politics were, and try and get out from under the shadow of his politics. Have you read Sontag’s “Notes on ‘Camp’”? She has a line in there that that sticks with me: “The two pioneering forces of modern sensibility are Jewish moral seriousness and homosexual aestheticism and irony.” That was how I grew up, in a household with Jewish morals.

To read Dave was a process of separating from parts of that moral seriousness. Twenty years from now, if one of my kids reads “Notes on ‘Camp’” and sees “Jewish moral seriousness,” it wouldn’t be shocking if they think of me. I’m more like my father than I’m like Dave, but there was a process to writing this book that involved an adoptive literary father who helps me venture out on my own path.

Daniel Nester is the author most recently of a memoir, Shader. Previous books include How to Be Inappropriate, God Save My Queen I and II, and The Incredible Sestina Anthology, which he edited. Recent work has appeared in American Poetry Review, The Collagist, Bennington Review, and Electric Literature.

This post may contain affiliate links.